“At the start of 1935, Merle Oberon feared her Hollywood career was over,” Mayukh Sen writes in the introduction to Love, Queenie: Merle Oberon, Hollywood’s First South Asian Star (W.W. Norton & Company). In 1934, Oberon was an established actress back in England, where she was often cast in so-called “exotics”—roles that capitalized on the Indian heritage she was already working hard to obscure. When she began working in Hollywood a year later, at the age of 23, gossip columnists speculated that her mother was “Hindu,” a term Americans used for any South Asian at the time. If the press discovered the truth—that Oberon had been born to a white father and Indian mother in the city then known as Bombay and grown up in poverty—the bigotry and anti-immigration laws of the time could have ended her promising career.

Instead, the speculation would never rise above the level of occasional gossip, and Oberon would pass for white for her entire professional life. She would become a star of the Golden Age in Hollywood, in films such as A Song to Remember and Wuthering Heights, and the first performer of colour nominated for an Academy Award for her role in the 1935 film The Dark Angel. She would undergo painful skin bleaching to maintain the cover story, initially constructed by a British film studio, that she had been born in Tasmania to affluent white parents.

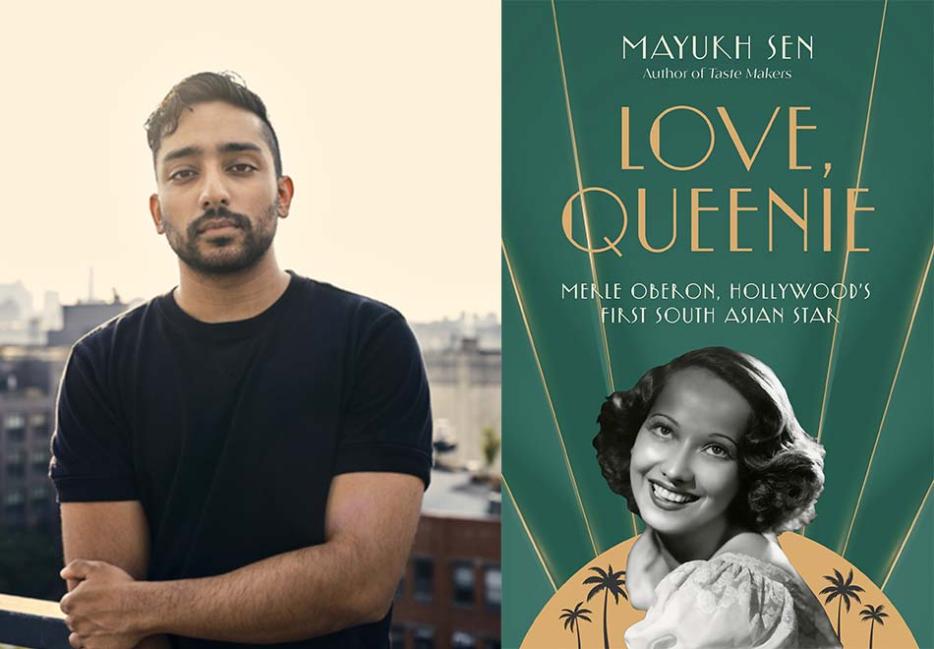

Love, Queenie is the first biography of Oberon published in forty years. Sen is no stranger to the genre: his previous book, Taste Makers, explored the lives of seven immigrant women who helped change the way Americans eat. But the story of Oberon, who passed away in 1979, presents considerable challenges to even an experienced biographer. Most of the people who had known and worked with her are no longer alive, and the many evasions she had to perpetuate in order to do the work she loved made it difficult for Sen to uncover her truth. Here was a woman whose life read like something out of a soap opera. A woman who, unbeknownst to her and her previous biographers, had grown up with a half-sister who was in fact her mother, and a mother who was actually her grandmother.

I spoke with Sen in January, shortly ahead of Love, Queenie’s March release. Reached at his home in Brooklyn, he was excited to discuss the book that he had in some sense wanted to write since high school. Our lively, wide-ranging conversation spoke to Oberon’s stranger-than-fiction life, Hollywood's restrictive beauty standards and history of racial exclusion—and how they’re still felt today—and the price of hiding in plain sight.

Rebecca Flint-Marx: In the introduction to Love, Queenie, you write that you knew of Merle Oberon from a fairly young age, but what was the spark for embarking on her biography, and what made you feel like this was the right time for it?

Mayukh Sen: I first came to Merle's work when I was an Oscars-obsessed high schooler. The summer right before my senior year of high school, I made it a point to study the history of the Oscars’ best actor category in particular because, I guess, I had nothing better to do, and I came across Merle's name. I’d grown up sort of knowing her name—I grew up in a Bengali family, and usually when people talked about Old Hollywood and its connection to Bengal, they mention Vivien Leigh because she was born in Darjeeling. Merle was sort of an ancillary figure in those conversations. But that summer, when I came across Merle’s name, I was totally stunned that someone who grew up in the same part of the world and in the same city that my dad was from, Kolkata, had gained entry into this world that seemed very closed off to my people. This was around the time when Slumdog Millionaire had come out, so there was this sort of hope among some of us that Freida Pinto would be the next big thing. So, to know that one of us really made it big, and had even gotten an Oscar nomination so many decades ago, just blew my mind. After that, I tried to seek out the film she was nominated for, The Dark Angel. At that point in time, YouTube was not the sort of robust library of classic films it’s become today, so that movie proved elusive, but I did track down a copy of Wuthering Heights. I remember finding her presence so spellbinding; she had this sort of star quality combined with a real acting ability that totally astounded me. I couldn’t quite believe that someone who had such a painful life offscreen—who had to hide this aspect of herself and her identity—could get up every single day to get in front of a camera and do work that brilliant. So, I always kind of had this fixation on Merle.

Kind of a magnificent obsession.

Yes, exactly. I had read the only other biography of her that exists, which was from 1983 [Charles Higham and Roy Moseley’s Princess Merle: The Romantic Life of Merle Oberon]. It’s not easy to write a book about someone like Merle because she was an unreliable narrator of her own life, and there’s just so much information to sift through. But when I read that book, I was a bit confused by its tone. It seemed to be a bit sensationalist. I think the authors had their hearts in the right place, but the end product just seemed so speculative. Charles Higham also had this pattern of peddling misinformation in a lot of his biographies, particularly those of Howard Hughes and Errol Flynn. [Higham claimed without evidence that Flynn had been a Nazi spy.]

No one was pressing further to connect the dots or question any of the claims that he made about Merle’s life, and that speaks to the fact that for many years people just didn’t care about Merle. It felt like I was one of the handful of people on this earth who did. When my career began about a decade ago, I got an agent and remember very distinctly telling him I wanted to write a biography of Merle, and he talked me down in a way that I think was very responsible of him. I was 25 years old at that point. I did not have a book to my name, and a single-subject biography of a figure as complex as her was going to be incredibly tough to pull off, and also not the most attractive prospect to a lot of publishers. When I published my first book in late 2021 [Taste Makers], I asked myself, “If you do have the privilege of writing a second book, what will it be about?” So, of course, I chose to make life harder for myself.

In your acknowledgements you describe Merle as a “biographer’s nightmare”—what made her so

When I first began my work as a journalist and especially when I was writing Taste Makers, I had this very naïve way of working, in the sense that I would usually build the foundations of my story or book chapters based on finding the subject speaking in her own words. With Merle, that process was complicated because she was working in a time in which she had to lie about her own life and maintain this fictional biography that had been constructed for her by a studio publicist in the early 1930s. And so, I had many questions going into this whole exercise of writing her biography, in terms of her childhood in India and what sort of discrimination she faced as a result of her mixed-race heritage and poverty when she got to Hollywood.

A lot of answers to those questions were pretty elusive for me because I essentially found myself facing hundreds of interviews with her in the press in which she talked about this childhood in Tasmania, which is where her publicist pointed to as her fictional birthplace. She would talk about these rich relatives who brought her over to India, where she lived in the lap of luxury. All of that was untrue as well because she was born and raised in India and lived in poverty throughout her childhood. It was very tough to sift through all that misinformation and drill down to the marrow of her story to find the truth. In retrospect, I can understand why there has not been a biography of her in 40 years. It was a very frustrating experience, but I was always so moved by her work that I wanted to endeavour to do this right. I hope I succeeded.

Merle’s maternal family was the Selbys, and in the acknowledgements, you thank some of its members. What was your process for reaching out to them, and getting them on board with your project?

I knew that was going to be one of the biggest hurdles in writing this book because I had so many unanswered questions about Merle and her early life, in particular. I even tried to write a version of an early chapter, kind of presenting those questions to the reader that I was very transparent with the fact that there’s so much that we didn’t know. My editor very correctly steered me in the right direction: she said, “This is not going to work. We need answers to these questions because you need to make sure your reader trusts you and you establish your authority as our narrator.”

Here’s how the whole process worked. In 2002 there was a documentary that aired in Australia called The Trouble with Merle, directed by a very wonderful and helpful-to-me filmmaker named Maree Delofski. In that documentary, she interviewed one of Merle’s half-siblings who was related to her via their shared mother. I found that man—he unfortunately passed away quite a few years ago—but I found his funeral home listing, which listed his next of kin. He had a big family, so I started plugging in names to a lot of these databases that some might find a bit sketchy and doing a lot of calls and emails. Eventually, I think I was about a year into the process of writing the book, I emailed this one person who was related to her and to my relief, he replied within three hours and was like, “Yes, I’m your guy, let’s talk.” I spoke to him and some other family members of his who he kind of roped in. We spent hours and hours just talking, and I would like to think the fact that I come from the same part of the world helped, but it did of course take some building of trust. I needed to at least convince them that I was not there to dig up dirt or tell a story in an insensitive way. I really just wanted to tell the truth of this woman’s life and honor her work as much as possible, and also render her biological mother, Constance, with as much sensitivity as possible. Because in that 1983 biography, she came across as a sort of disagreeable figure, and that was partially because the biographers did not know that Constance was actually her mother. She had her at 14.

Oh, my god.

And really just knowing that fact, which wouldn’t become public knowledge until 2002, cast her interactions with Merle and her correspondence with Merle in a completely different light. These family members of Merle who I spoke with grew up with Constance in the house, so I got such rich insight into her life and what her circumstances were like after Merle left India and became this huge star abroad—how this woman had talked about Merle, who she maintained even in front of her family was her half-sister, even though she was her daughter. That’s something that not even the family knew until they came across Merle’s birth certificate in the early 1980s.

I was so relieved, honestly, when I found [the family]. It’s the kind of moment that I think every journalist, every author craves—there’s one crucial source that you know you need for a story to really sing and everything to kind of fall into place.

One thing that struck me as I was reading was that Merle’s time in the sun was so brief; she appears in The Private Life of Henry VIII in 1933, gets her Oscar nomination for The Dark Angel in 1935, stars opposite Laurence Olivier in Wuthering Heights in 1939, and then only a decade later, her glory days are behind her. Despite her incredible triumphs, did the relative brevity of her career make it more challenging for you to portray her as an actress who had been unjustly forgotten? Because I think more cynical people could look at it and say, “Oh, well, she barely did anything.”

That’s a great question because in one respect, it was kind of freeing that her filmography is skimpier compared to that of, let’s say Bette Davis or Joan Crawford or Barbara Stanwyck. One of the challenging things of writing a biography, I’ve learned, is that you don’t want your book to read like a Wikipedia page, where you’re essentially providing a walk-through with film summaries and a sentence or two devoted to what her performance is like. I even found myself falling prey to that trap in the 1940s chapters, where there’s a string of less than remarkable films that she starred in, and she herself was kind of on autopilot in a lot of these performances. [Because] I didn’t have to fixate too much on performance analysis, I could instead devote proper time to her personal life and the dramas, for lack of a better term, which were consuming her offscreen.

It gave me clarity, too, in that I had a very strict stipulation from my publisher that this book should only be 75,000 words or so because already, a single-subject film biography of someone who is no longer a household name is going to be a tough sell to a lot of readers, so you want to make sure that the book is as brisk and engaging as possible. Early in the whole process, I [asked myself] what I wanted my readers to understand and take away about Merle, and I think that approach helped me. It forced me to be like, “Okay, this is an interesting detail, but it might not be consequential to the overall story that I want to tell.”

So much of what was interesting to me about the book was this kaleidoscopic approach you took to Merle’s life, in the sense that we’re learning about her movies but then we're also learning about the broader context of, for example, immigration laws in the United States, and the more informal laws governing the Hollywood studio system. So, the reader sees how much hiding Merle had to do in order to just do her job, but then also how she was only able to do that because so many people were complicit in her secret, like The Dark Angel crew who made her bleach her skin. You write that if people in Hollywood liked you then they’d protect you, and that Merle was very well liked, and worked hard to be liked. But I wondered how much of that was a condition of needing other people to keep her secret.

I think that she realized pretty early on that she would need to make a lot of friends in high places if she were to have a Hollywood career. We see versions of this play out through a lot of old Hollywood history—like Rock Hudson. He was surrounded by a number of people who really protected him and kept his secret. The sense that I got through my research and reporting is that having grown up in poverty, Merle had the survival instinct baked into her and knew what she needed to do to have as peaceful and secure a life as possible. I’m kind of wary of framing her story as a tragedy because it is so much more than that—she did really work against all these systems that were oppressing her. It was not just Hollywood and the injunctions of the Hays Code; it was also America’s wider perception of South Asians, and the fact that immigration law was such that she couldn’t be open about her heritage if she wanted to have a permanent life here. Indians were only permitted to come to the country as visitors or tourists until 1946, and even after that point, she was too timid to obtain American citizenship because she knew that process would inevitably be publicized, and then her whole studio-constructed biography would come crashing down, and her public life would essentially be destroyed. I think what she did, very shrewdly, was keep the Hollywood high society in her favor.

The fact that she had to live this lie throughout her entire life in public, is a tragedy, and it’s an indictment of America. It's an indictment of Hollywood. It’s an indictment of all these other systems under which she found herself operating, and I don’t want people to forget that, because part of what I want my readers to understand is that what she had to go through should never happen again. Someone should not have to live this sort of lie in order to do what they love, and I had to balance that truth alongside the triumphs of her life and how she was able to do this through her charm, her hard work, and her luck. She was able to make a life for herself against the odds and that is absolutely worth celebrating, but we also need to acknowledge the factors that were holding her back.

It reminded me of what actresses, in general, have to do in order to be liked, even today. If you’re considered difficult, you risk damaging your reputation and career. Even though Merle was well liked in Hollywood, I was struck by the cruelty of how the press wrote about her, specifically regarding her appearance as she got older. Was that shocking to you?

All those years ago as a high school senior, one of the things that I often read about Merle was that she was a great beauty. Even people who had very low opinions of her acting, or said she should be disqualified from any conversations about racial progress in Hollywood because she passed as white, they would always concede that she was one of the most beautiful Hollywood figures from that era. However, some of my research contradicted that. From the moment she gets to Hollywood, there are some people who just say plainly that she is not beautiful, or talk about her hair being all strung out, or her looking kind of flatter. It really does underscore the fact that when she came to Hollywood, she really was of a different type.

The cruelty really becomes more intense as the years go on because first of all, her skin gets noticeably darker. She also has to deal with a variety of threats to her beauty—she’s involved in a car accident in the late 1930s, and then she has this horrendous medical episode in 1940 that really damages her skin, [she had an allergic reaction to sulfa drugs she was taking for an illness], and then later on she starts seeking plastic surgery, in part because of alleged domestic violence she survived. [Lucien Ballard, her second husband, allegedly struck her during an argument and she suffered very visible injuries.] As a result, you start to see the press get a lot meaner. To me—and I want to be careful here and not sound like someone who is grafting 21st-century ideals and morals onto the past—but I very plainly see a lot of these comments as shaded with xenophobia or racism. The ways her beauty is described are statements of her differences from the norm of white beauty that a lot of Hollywood women were supposed to represent.

A lot of those comments did feel racially coded to me, certainly enough where it was like, okay, they wouldn’t be saying this if she had blonde hair and blue eyes.

Exactly. You can also see it in the way so many newspapers, around the time she came to America, would speculate that her mother was a “Hindu,” which back then was just the term for anyone from South Asia, regardless of whether they were Muslim, or Sikh, or actually Hindu. And when paired with those comments about her olive complexion or the darkness of her hair or her very high forehead, all this sort of crystalizes.

In the book’s introduction, you write that you hope that the reader might start to question the demands the public places on stars, both in life and death, and how those demands intensify when performers come from underrepresented groups. I think that’s something we still see a lot today, in an era that’s considered more enlightened than the one Merle lived in. I’m curious if writing the book changed the way you thought about those kinds of demands, and the parallels that exist between Merle and contemporary performers of colour.

Yeah, that part of this entire equation did not become clear to me until I was late in the drafting process. It was in the middle of writing this book, in early 2023, when the Oscar nominations for 2022 came out and Michelle Yeoh was nominated, and eventually won, for Everything Everywhere All at Once in the Best Actress category. Her nomination made her the second Asian actor, if we’re going by the definition of Asian that’s East, Southeast, or South Asian. That led to a flurry of interest in, and judgement of Merle, from an entirely new audience; people of my generation who purport to be enlightened or progressive in some ways, but in fact might be quite curious about the past and the standards with which so many people of colour lived during that time and the racial hierarchy that was governing their lives. And I saw so much judgement cast on Merle by so many people who kind of declared themselves to be spokespeople of the Asian American community, people who essentially said, “You know, if Merle didn’t count herself as Asian, I’m not going to count her either.”

To me that is such an unfathomably cruel way of looking at the world. It essentially says, “You know what? This person’s existence makes me so uncomfortable that I am just going to avoid dealing with that discomfort at all.” Because her life does force you to deal with uncomfortable truths about the way this country once worked, and the way certain members of our community did get excluded. But it did force me to draw parallels to what we see in today’s entertainment landscape, where it does remain the case that there are still very few South Asians in Hollywood. Dev Patel, Riz Ahmed, and Ben Kingsley are the only other South Asian actors who have been nominated for acting Oscars, and [aside from Yeoh] there has not been a single other Asian woman nominated since Merle.

I’ve seen time and again instances of someone breaking through in some visible way, but maybe one of their creative decisions ignites intense backlash from their own community, and their existence becomes an indictment of our entire community. And some people within our community can be the harshest critics. Writing the book taught me to have a little more grace when it comes to certain people who might find themselves to be the only representatives from a specific group or demographic to be thrust in the limelight. I think we’re all human. That doesn’t mean we can paper over excuses and mistakes, but I think it would make sense to just be a little more generous in our outlook towards people and acknowledge that they have foibles like the rest of us. Yes, stars might have access to certain privileges that I and others will never enjoy, but we have to see their humanity because otherwise there’s not going to be any progress when everyone is held to a certain kind of standard that is impossible to meet, How else is this industry going to move forward in any sort of way? We just need more representation, so that an individual like Anna Mae Wong or Merle Oberon isn’t going to be saddled with these expectations that people forced on them.

It makes me think about Kumail Nanjiani, who received a ton of attention and scrutiny when he transformed himself physically from a sort of textbook 90-pound weakling to this totally ripped, jacked-up action hero. Obviously neither you nor I know his mind, but do you see something like that and think about the pressures that Merle experienced over 80 years ago?

Oh, absolutely. I would say that there are definitely parallels because a lot of what Merle was doing was trying her best to fit in. We were talking about the press’s cruelty regarding her appearance, which today does register as shocking. A way to deflect any of that sort of criticism would be to blend in as much as possible, because she was working in an industry where her differences from the norm was not necessarily an asset. It was fascinating, because what my research taught me is that her racial ambiguity had really been her stock and trade [when she started out in the British cinema]. It allowed her to play a very wide variety of roles. She could play a French noblewoman, or a Spanish dancer, or a Japanese woman. But when she came to America, given especially its hostility to South Asians, she essentially had to do everything she could to convince her audience and the industry that she was white and nothing but. And so, you very rarely saw her play any roles that suggested she could have any sort of mixed heritage at all.

By that same token, any procedures she was subjected to by the studios were in service of her blending in. For example, when she’s filming The Dark Angel, the crew feels her skin is too dark and they force her to undergo an entire day of skin bleaching in a local beauty salon. I think of course our standards of beauty change, but it still remains the case that there are certain kinds of physiques and appearances that are seen as marketable by this industry, and that puts a lot of performers of colour—and certainly South Asian performers—into a sort of compromising position, where they might face a choice where their difference is either going to work in their favour or it’s going to be a liability. And more often than not, in my observation, it does turn out to be a liability. And that’s why you might see a sort of drastic change in appearance among certain actors, because they want to fit in and be seen as viable for roles. And that’s where one might think the progress comes, right? In seeing a South Asian face in a leading role. But it comes at a cost.

It makes me think about privacy, too, and the differences between what it meant during Merle’s time and what it means now, when many people use their private lives in service of building and shaping a personal brand. It was incumbent upon Merle to be as private as possible about certain parts of her life, and that seems like it would create some tension for a biographer. Because, on the one hand, you have a duty to delve into your subject’s private life in a way that’s respectful, but on the other hand, it has to be incisive and enlightening to the reader. So, I’m curious how you approached that, and what kind of responsibility you felt towards Merle as her biographer.

Oh man, that was top of mind for me as I was going through the process of writing her biography. What I ultimately wanted to do is tell the truth of her life because she was not in a position to do so when she was alive. But I also wanted to maintain a level of respect. I think the fact that I was coming to this project not with a sense of wanting to dig up some dirt on her, but to really just honour her and the nature of her struggle without necessarily making her into some sort of softened heroine—I needed to make sure the moral contradictions were there on the page. All of that was really important as I began writing, but it was tough, too, because essentially what she did throughout her entire life was keep people at arm’s length. There were very few people who she let in, and those people are no longer alive, so it’s not as if I could speak to them about what it was like. Working through that sort of roadblock involved spending a lot of time with her personal papers. They’re highly curated and there’s not a lot about her personal life that would have been of interest to me as her biographer who wants to make sure that the truth of her life is reclaimed in some way. A lot of [her papers] pertained to her social life in the ’60s, for example, when she had the life of a socialite, so that didn’t really serve me well.

But what I did learn was how to read between the lines to locate her humanity as much as possible. So that meant that if there was an offhand line in an interview, where she talked about how when she first arrived in New York in 1934, she felt so overwhelmed, I told myself you need to use this, to slip under her skin to the best of your ability and make sure your reader understands how she felt in a certain moment. I learned to be eagle-eyed as I was reading the archives, but ultimately there’s only so much you can do. I started to fall back on context and ask myself what was going on in the world that may give us more insight into certain decisions that she made. For example, I was struck in my research by her admission to a gossip columnist that she wanted to return to India. I was asking myself what would motivate that, and it made me realize that was around the same time that immigration from India to America was finally being legalized as a result of the Luce-Celler Act. I think that just forcing myself to map her story against these broader social and political currents really helped a lot of these questions to gain answers they previously didn’t have, and subsequently, I hope, made the book feel richer. When I began writing this book, I very naïvely assumed it was just going to be a straightforward womb-to-tomb account of this woman’s life and the fact that she passed for white; I wasn’t even connecting the dots. And once I forced myself to really do that, a lot that once confused me about her life started to make sense.

You came into this knowing Merle’s basic history and also had no illusions about the inequities of Hollywood, particularly during the Golden Age, but I’m curious how delving into the more tragic and unjust elements of both affected you?

I mean, I’m not usually Mr. Waterworks, but I did cry while writing this book. I’m still at the point where sometimes I will see her face or watch a clip of one of her movies and just think about how much she survived and how astonishing it is that she was able to have this flourishing career. Yes, you could say that her time at the top was short-lived, and there’s a sort of gravity there, but the fact remains that she really was able to gain access into this club that was not designed with the likes of her in mind. I think what allowed me to, I hope, make sure that her complexities were on the page is that in so many ways I did relate to her. Obviously, I’m not a screen actor, and I did not grow up in poverty, but there were aspects of my personality that I started to see in her the deeper I got into my research. I don’t want to sound like I was projecting myself onto her, but there were so many moments in which I found myself thinking, “Oh wow, this reminds me of this moment in my career.” And I really related in particular to her desire to just have comfort and stability. I think that when you’re in that sort of position as a biographer, where you do relate to your subject in some way, and you see aspects of yourself in them, it also allows you to become more honest about their flaws.