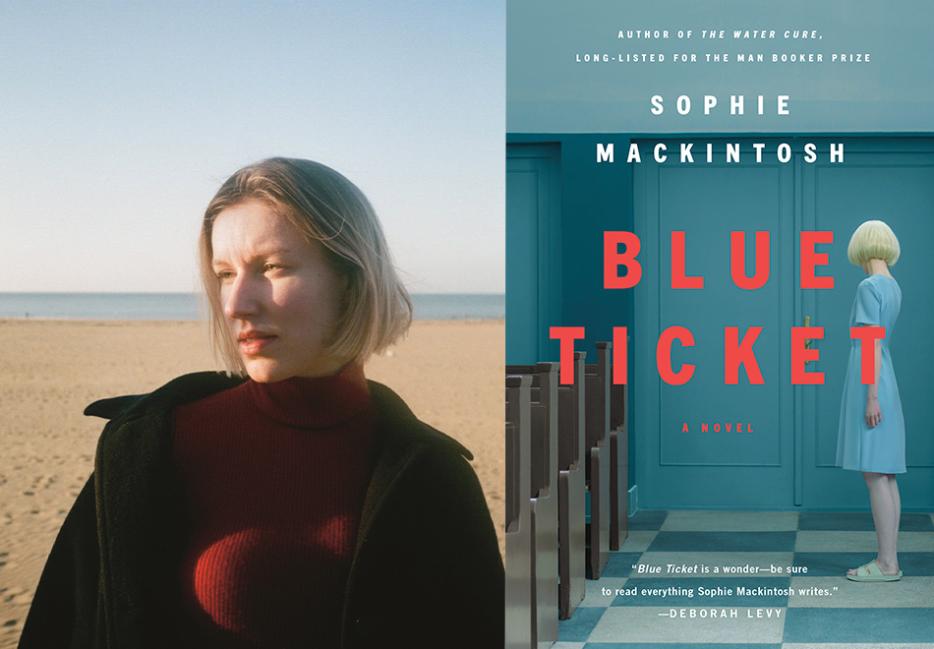

Sophie Mackintosh’s second novel imagines a world in which women’s decisions around pregnancy and childbearing are decided by a lottery. A white ticket gives you children. A blue ticket gives you freedom. The novel’s anti-heroine, Calla, soon falls pregnant even though it was her predetermined destiny not to. She hatches an escape plan, but discovers it’s not so easy to make a clean getaway, or figure out who you truly belong with. Mackintosh isn’t one to shy away from difficult, messy, daring interrogations of how women are seen—and treated—in so-called modern society. Earlier this year, she told British Vogue, “I want to be doing work that makes a change”.

A Welsh writer based in London, her debut novel The Water Cure, which was long-listed for the 2018 Man Booker Prize, is a multi-voiced, slow-burning novel told from the perspective of three sisters stuck on a remote island. Their parents run elaborate, primitive purification treatments for women harmed by men from the outside world. Written during Brexit and the rise of Trump’s political power, the narrative considered the depths of toxic masculinity: what does it mean to be poisonous to those around you? How does unfairness spread like a disease?

“We need a wider range of language to describe these books instead of writing them off as angry feminist dystopia,” Mackintosh pointed out in an interview with BOMB Magazine last year. “These are our real concerns that we’re writing about.”

Blue Ticket (Hamish Hamilton) considers female pain, power dynamics, and how we define the true self in a way that sometimes makes the prose physically painful to read. Yet underneath the layers of toughness, a tenderness comes through—one that asks not to be judged; an understanding that resists being reductive.

Sophie and I spoke in the lead-up to the North American release of Blue Ticket, while the city of London was still in lockdown.

Nathania Gilson: In the acknowledgements of Blue Ticket, you mentioned that you spoke to many people about their experiences of motherhood and babies as part of your research for this novel. What surprised you the most?

Sophie Mackintosh: Seeing first-hand the exhaustion and shock of new mothers; the fragmentation and the loss of sense of time really made me understand, a little more, the magnitude of the change.

I knew it changes your life, of course, but I didn’t fully understand that a newborn only sleeps for a couple of hours at a stretch, even in the night; that their tiny stomachs mean they need to be fed near-constantly. I somehow had the romantic idea that you have the baby and the first weeks and months are this milky, dreamy time where the baby just sleeps while you regather yourself, and then you just carry the baby around with you and carry on as normal.

Also hearing about the physical effects. There are so many weirdly occult, horror-movie elements to it. The nightmarish idea of a forty-eight-hour labour before somehow being discharged with a new baby that needs you so much and a sleep debt you’ll never pay off; of bleeding and tearing, pelvic fractures, the sheer bloodiness and danger of pregnancy itself.

For example, I read somewhere the theory that we evolved periods because pregnancy is such a risk—a biological tug-of-war with the mother’s body—that our uteruses just violently purge themselves monthly in order to take no chances.

And that newborns will have a tiny period because they’re full of all the mother’s hormones. That freaked me out! And yet, having seen all this and heard of all this and learned all this, I still want to do it.

Hearing you talk about the painful reality of being a mother or bringing a baby into the world, it reminds me how much “baby literature” exists in the world. Not just the self-help books that try to prepare you for it, but the myth-making involved, too. Babies being thought of as miniature sphinxes, dignified emperors sat in their prams, seeming powerful and fearless when they refuse to cry. I’m thinking of the Rachel Cusks, Sheila Hetis, Jenny Offills, Pamela Erenses, Lydia Davises, Raymond Carvers, and so on, who have their own interpretations. In the Western world, where it can seem like canonizing or creating “important” literature is the end goal, perhaps, how do you go about making your work feel like it’s yours?

I think maybe by keeping my expectations low, or maybe a process of acceptance. To both know that I’m writing about subjects that historically have maybe not been seen as important, and also to know that, in the scheme of things, my book is just a book.

To recognize realistically and humbly the smallness of my work, maybe. Not in a way that's self-deprecating, but in a way that's freeing.

To realize that there are a million takes one can have on any subject, and this is just mine. And to think of it in conversation with the others, perhaps, but finding its own way and interpretation.

Blue Ticket is so full of sights, smells, and sounds that make it feel not so far away from the world we’re in now, and yet. There’s a certain rhythm and cadence to Calla’s thoughts that feels hypnotic and otherworldly. I was wondering how films influence your writing process, or if the experience of watching films is a space where ideas come to life for you?

Often when writing I am trying to pin down a feeling as much as an image, and using every tool at my disposal to try and get there. By the end of writing a book, it feels like its own film which takes place in my head.

Some films that I was thinking about and watching or re-watching when writing Blue Ticket include [Yorgos Lanthimos’] The Lobster, [Michael Haneke’s] The Piano Teacher, and [Lynne Ramsay’s] Morvern Callar, as well as road-trip movies like [Ridley Scott’s] Thelma and Louise. I'm easily soothed by beautiful images.

I feel a certain shame sometimes that my approach to writing is more emotional rather than academic—I feel like I should just know more about theory, or the process of writing as an art form. Instead it sometimes feels like blundering around a thousand messy drafts trying to get at something more indefinable, the way a song can transport you or remind you suddenly of somewhere you’ve never actually been.

That subconscious feeling you describe reminds me of an interview that the novelist and visual artist Leonora Carrington gives, where she tells off her great-niece for trying so desperately to intellectualize art. She said we should trust our own feelings about things instead. Instead of “getting” something, we can try accessing the part of our brain that feels more honest, because it’s less weighed down by ego.

I think intuition and heart (for want of a better word) count for a lot.

You could execute the most technically brilliant and flawlessly researched novel in the world, and it could leave you cold.

I like the unconscious connections, the things that come together when you're least expecting it, and the messiness of my own writing process facilitates this; I redraft and rewrite and distill obsessively because I never know what tangent I've gone off is going to prove to be the unexpected core of the work.

Though maybe it's easier for me to think like this rather than interrogate what could be my intellectual laziness, so I'm more conscious now of striking a balance.

I think some of it also comes from feeling slightly like an imposter. I used to get anxious discussing my own work, as if I could somehow get that “wrong,” when I wrote it, which is absurd, really!

If I had built myself a fortress of theory and technique it might have been easier to talk about it. If something does come from an emotional place, it does make it that much more tender.

Desire, luck, choice, and “badness” (as the opposite of goodness) come up frequently in the novel. How was the writing of this story a way to shift or challenge the binary of what is possible for women in this world?

I think we internalize—and externalize!—the concept of “good” or “deserving” so much, and especially when it comes to women, and then further still when it comes to mothers. There’s still this expectation that you have to be obviously maternal. Some readers find it hard to accept that someone like Calla would have a baby, or should have one.

There’s still so much buy-in to the Madonna-whore dichotomy culturally, and I’m interested in how we interrogate that. This expectation of docility; how reproductive sex—as opposed to sex for pleasure—seems a whole different beast in the way we regard it (although I don’t know why that still strikes me as faintly absurd because I know we exist in a puritanical society where pleasure for pleasure’s sake isn’t really trusted).

Also, I wanted to challenge the idea that only a “good” or “nice” character is deserving of being loved, or getting what she wants. Because, actually, having a baby is both quite democratic and wildly unfair.

Women castigated culturally as “bad” mothers can do it and “good” mothers can have fertility problems, and everything in between. No matter how maternal we are, our bodies can betray us. Maybe we cling to these ideas because they give us some sense of control; that if we’re “good,” we’ll get what we deserve.

I know Calla does that sort of bargaining [in the book], and I’m familiar with it, too. I’m aware that she’s a difficult character to root for because she does go against our ideas of what a “deserving” mother looks like—there’s drinking and there’s smoking and there’s indiscriminate sex and selfishness—and you know these things are actually not so bad in the larger scheme of things, but for a mother to be these things still does feel like a taboo.

And what does that say about us? It’s quite revealing. We can be as modern as we like but we still assign these moral values.

When you were a teenager, what books made you feel known and seen? Do these books still matter to you now, or have other books been important to shaping how you think?

I think the main one for me was The Magic Toyshop by Angela Carter, which was important to me both because of the language and style. It was so eerie, gothic, and lavish—otherworldly whilst also still being part of the world—and because it gave gravity to the experiences and internal life of a fifteen-year-old girl, which at the time (alongside reading mostly the Great Male Writers and plenty not-so-great), I didn’t know was necessarily something that could be the subject of literature.

Every couple of years I’ll read a book (like Bluets by Maggie Nelson, or In The Cut by Susanna Moore), which totally cuts through everything I thought I knew and reinforces for me the power of language.

How has growing up in Wales influenced the way you see the world?

I felt quite isolated growing up, always very eager to get out, but at the same time it was a very special place to grow up (though when I was younger I was very indoors and definitely took this beauty for granted, I just wanted to be inside).

The entire coastline of Pembrokeshire, where I’m from, is a National Park. The landscape feeds into my work for sure, most obviously in The Water Cure, which is based on a real beach that I’m familiar with.

I’m fascinated with both the beauty and the uncanniness of the natural world. In the places as remote as where I grew up, it’s quite overwhelming, but also quite eerie. You can imagine magical or unreal things taking place. And dangerous things, too. I’m aware that nature can really turn on you; that you never know what rip-tides are underneath a smooth surface.

As I got older, and more independent, I started to realize the possibilities of such a landscape; of a kind of freedom, and started to appreciate it more. I was also educated through the medium of Welsh until I was eighteen, so I’m a fluent speaker, and while it’s a cliché to call it musical it just really is a musical language! My school was very big on making us learn Welsh poems and songs. So, I can see how this switching between languages and the emphasis on the lyrical, rhythmic side of it has influenced my writing. I always do entire read-throughs of my work to myself to see how it feels and sounds.

Rage, anxiety, and compulsion spill out a lot in Blue Ticket. The characters are not always kind to each other, or themselves, in a universe where it’s hard to know who to trust. I was wondering how you find—or create—healthy ways of channeling these emotions into your writing? I was also interested in the challenges of writing visceral terror or violence in a way that feels familiar (or easy to empathize with) to the reader?

When writing visceral emotions I usually start from thinking about it bodily; really slowing it down. This is something I still do now when I feel something uncomfortable. I think about exactly how I’m feeling in my stomach, my limbs. I try to name the feeling, and make time stop. But I don't want to be gratuitous when describing violence, and I think that leaving things unsaid can often be more powerful.

I think we often disregard female pain and anger as histrionic or self-indulgent, but it feels important and interesting to me—worth writing and thinking about.

Some people will lose patience with Calla making terrible decisions again and again, and the fact that she’s not necessarily repentant about her compulsive or bad behaviour.

It’s not all from a place of emptiness—she also just is quite selfish and likes to have a good time without really thinking about the consequences, and also would really like to be a mother, and actually, those things can all coexist.

The characters in Blue Ticket are pregnant women essentially competing against each other for resources, unable to really trust anyone, and underneath it they can barely trust themselves, because their bodies are changing and their desires are alien to them. That sense of dislocation was important for me to represent, and the idea that a pregnant woman isn’t necessarily sweetly domestic, but rather could be very ruthless if needed; rageful.

There’s an incredible, incidental scene where Calla’s wandering around in the supermarket at her own leisure, and it struck me, as we navigate a global pandemic, how her experience of it challenges the rituals we have—or have lost—now. She says, “The supermarket made me feel safe. Even in childhood I had believed that nothing bad could happen in a place of plenty.” People often think dystopia is the blockbuster film with special effects, complex choreography and a dramatic soundtrack. How do you set out to write against this—or perhaps, point our attention elsewhere?

A funny thing is that I wasn’t really setting out to write a dystopia. I didn't with The Water Cure, either, and am not even totally sure I did. I wanted to write a place that wasn’t ours, in which the rules can be different, and that automatically puts you in a dystopia and then sets up many expectations; the world-building.

Perhaps my books are more quiet dystopias. Semi-dystopias? They’re always more focused on how someone navigates the world rather than on how that world came to be.

The hypothetical bind is the thing. I think many people can identify with that secret fear that you are one sort of person, and you want to be another sort of person but even if you try very hard to change, to be “better” or even just different, you can never really shake that off—that there’s something intrinsic in you, often something shameful or small that you’re afraid of people seeing.

It’s kind of a nightmare, that idea that your soul is basically visible, and found lacking somehow. That Calla wants this thing so desperately, and the judgement is that it’s not for her; she hasn’t reached some kind of invisible and arbitrary standard, and never will. That’s before even thinking about all the societal expectations around motherhood, and the fact that we still live in a world where many women lack bodily autonomy.

I’m trying to dig into our deepest fears rather than make a political statement. I wanted the world to feel real to us, to be populated with feelings we can understand and set-pieces we recognize, so that when things are off-kilter we feel that jarring somewhere deep inside us, that sense of something being wrong, somewhere.

Blue Ticket did start off more explicitly as a horror, actually. I started with the image of a bloodthirsty, cannibalistic pregnant woman tearing people to shreds. And I’m working on a weird historical fiction at the moment, which nobody could ever describe as dystopian, and yet the process of writing historical fiction also feels, to me, embedded in a speculative tradition: “This could have happened, but this happened instead. But what if it happened this way?”

I wasn’t expecting Blue Ticket to make me laugh. But it has moments of humour that sneak up on you. There’s a scene in the book where Calla walks around a hotel barefoot, and meets a man at the bar. “I ate them,” she says, when pressed for an explanation about her shoes. Why is humour an ideal coping mechanism in a universe where so many things can go wrong when you’re a woman?

Humour can be such a shield. If you laugh at something, you can pretend you’re not bothered by it.

For someone like Calla, who doesn’t want to reveal herself and wants to make sure she comes across as cold and ruthless, laughter can be a weapon, too. A way to take people down a notch as well as distancing herself from having to care. She doesn’t have much else except for her sense of self and ability to react to a situation. So, laughter it is.

The names women make up for each other in this world out of affection, or to hurt each other, stood out to me: “swamp monster,” “queen ant,” “cold fish.” Why the comparisons, rather than using birth names or initials?

I wanted them to develop something like their own intimate, coded language, the way that lovers and friends do. It’s primarily affectionate, but also hurtful when you turn an affectionate name or mechanism of naming around and use it to be negative.

Also, I kind of saw it as their feeling an affinity more with the natural world around them, which to them at various points has been terror and salvation, their turning away from the cities and pasts that has saved them.

Calla refers to herself as a failed experiment in the book. Her doctor echoes this sentiment at one point: “I thought you had potential,” he says. “Sometimes I made admiring notes.” What advice would you have for writers who are sweating over the details of career trajectories, and perhaps afraid of the future?

There are so many ways to be a writer, so many trajectories you could follow, and so many timescales. There’s a lot happening under the surface, but publishing loves a shiny story rather than thinking about the—frankly dull—legwork that goes into creating books. Plus, we all have lives. Things happen to us whether we choose them or not. I've had the luxury of a quiet few years where I wasn’t caring for anyone or moving around a lot or experiencing major tragedy or change, where my primary responsibility has been to pay rent.

I had a full-time office job that was interesting and left me with the energy and headspace to create things. I didn't feel lucky for all this at the time because I was too busy comparing myself with other writers who were living much more successful and glamorous-seeming lives with not a water-cooler and commute in sight. But I really, really do feel lucky now (especially now).

Give yourself a break, basically. Because it’s easy to look at biographies and think: Oh, this person went to this prestigious university, and then gained this prestigious MFA right after, and all the while was being published widely, and of course their first novel was snapped up for a giant advance at the age of twenty-three, or whatever. To think that’s the trajectory for everybody, and if you’re not on that trajectory yourself, that you’re failing already...

That wasn't my trajectory by any means (I got rejected from every MFA I applied to and wasn't widely published), and it's not the trajectory for so many writers.

I can understand being afraid of the future, especially now, because everything feels different; everything feels so up in the air.

Talking about trajectories almost feels odd, because what is a trajectory now? How do we move forward and what will the systems we're familiar with look like? So, I think it's more important than ever to concentrate on your own writing journey, however you're able and whatever that looks like for you, rather than try and keep yourself on some arbitrary path or timescale.

It might look different to what you expected, but it's yours. Write what nourishes you and what speaks to you in this weird, strange time. Write and don't be scared to write or feel that it's pointless, because I don't ever see a time where we won't need books, where we won’t need to see our world refigured and reflected, to know we’re not alone.