If you are a person who, for ethical, environmental, or health reasons, chooses not to consume animal products, at some point or other, you will be asked: “How do you know if someone’s a vegan?” A pause. “Don’t worry, they’ll let you know.”

I’ve heard—and even told—that same joke many times in my own life as a non-meat-eater. Alicia Kennedy recounts it early on in her first book, No Meat Required: The Cultural History & Culinary Future of Plant-Based Eating (Beacon Press). She brings it up to show why many people have moved away, as she does in her book’s subtitle, from the labels “vegan” and “vegetarian.” But she also makes the more trenchant point that, in fact, nothing makes a person talk about their love of beef more quickly than you telling them you don’t eat it.

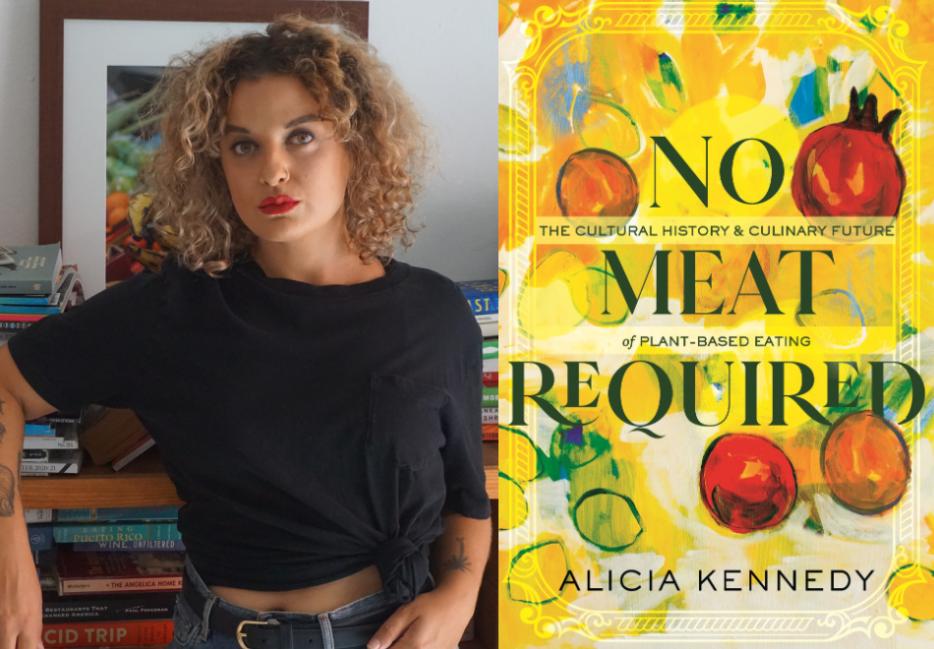

Insights like this—surprising, personal, a bit ornery, and which thoroughly reconsider and reframe our relationship to food—are Kennedy’s stock-in-trade. Since 2015, she has written on food and culture for, among other publications, the New York Times, Bon Appétit, Foreign Policy, and in recent years, produced a popular weekly newsletter, “From the Desk of Alicia Kennedy”, and a podcast of the same name. Her Instagram stories are a reliable source of recipes, rants about food politics, stunning shots of some very original meals, and cameos by her dog, Benny, and husband, writer Israel Meléndez Ayala.

Unlike most other food writers, frequently omnivores, who rarely address the thorny questions surrounding the production and consumption of food, Kennedy doesn’t eat meat and very intentionally, forcefully, dives into the environmental, labour, and cultural issues bound up in what we consume, and how.

No Meat Required is both the natural culmination of all this work, and an inspiring leap forward: a comprehensive, deeply researched, opinionated chronicle of vegetarianism and veganism in the United States. It’s also an account of Kennedy’s personal journey, from Long Island omnivore to punkish Brooklyn vegan. (She currently lives in Puerto Rico, and now identifies as vegetarian.) Along the way, she takes on Big Tech’s addiction to fake meat, wellness culture, and the transformation of plant-based cuisine from “hippie food” to luxury consumer good. Kennedy can be undeniably earnest—“Until there is a major reckoning with the cashew,” she writes in a chapter on non-dairy dairy, “questions on sourcing must be asked.” She is also funny, dogged, and compassionate, expertly synthesizing decades of history, cultural analysis, and political theory. The result is necessary and long overdue. If you grow food, buy food, or eat food, it’s a book you should read.

I spoke with Kennedy in early July—she was in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and I was in Toronto.

~

Jason McBride: I remember very well when I first read you: a piece you published on nut milks two years ago. It was so smart, vigorous, persuasive, and, especially, unapologetic. A sense of apology is something that, as you say in No Meat Required, accompanies a lot of vegetarian food writing. Is that unapologetic-ness just part of who you are or is that a voice you’ve tried to cultivate in your writing?

Alicia Kennedy: I think it’s definitely who I am as a person. But it’s also something that I’ve realized is necessary when you’re talking about these things. When I started writing about food in 2015, people were so incredulous about a vegan writing about food or a vegan taking vegan food seriously. It was just absolutely ridiculous to everybody. Until I was at the Village Voice for a while, I was constantly coming up against editors wanting me to present all this as strange, instead of something as normal as nut milk, which has roots in 12th-century Iran. Even now, there are still people who, even when they write about the hot new vegetarian restaurant, want to be like, “this is isn’t like any other vegetarian restaurant that came before, this is different, this is good.”

When I write, I take the posture of the unapologetic vegetarian. I wanted, especially in this book, where there’s so much history, to make the omnivore who’s reading feel like the weird one for not having taken any of this seriously.

That cultural and political history is so comprehensive in the book. You point out that many cultures have long histories of plant-based cuisine. But you also write that some vegans, especially ones who come from non-Western cultures, run into problems of authenticity because meat has become so central to almost all cuisines. They’re told that if they’re vegan, then they are not, say, authentically Mexican or Chinese.

Yeah, there’s this idea that there’s a lack in vegan or vegetarian food that cannot be compensated for. That perception of lack is why the whole concept of vegan or vegetarian food is so ripe for a takeover by corporate food businesses. I wanted to push against that by bringing up the folks who, whether it’s been hundreds of years or thousands of years, or just the last fifty years, have been taking a whole foods, plant-based approach very seriously and creating so much cool stuff with food that can’t be copyrighted or genetically modified or profited from. There’s real culinary creativity in cooking, in recipes, in the kitchen—in the domestic sphere—that gets discounted when we try to talk about vegan or vegetarian food as something where you’re just replacing the meat or the dairy or the egg.

You could have written a cookbook as your first book, and included some of this information or thinking as introductory context. But instead, you chose to write a complete, detailed cultural history. How come?

It would have been interesting to do a cultural history through cookbooks, kind of like The Jemima Code by Toni Tipton-Martin. I think that could be done, and should be done. But my obsession with vegan and vegetarian food has always been about the culture surrounding it. When I was younger, like in the late ’90s, early 2000s, I just thought everybody who didn’t eat meat was super-cool. Then, the more I dug into the food part of vegan and vegetarian history and culture, the more I found these pockets of interesting subcultures surrounding them.

My whole entry point into thinking that vegan food could be really good was Lagusta Yearwood, a chocolatier in upstate New York that I write about in the book. Through Lagusta, I found out about Bloodroot in Connecticut. And through that restaurant I found out about eco-feminism, and I was like, “Oh, my god.” I know folks like Jonathan Kauffman, who wrote Hippie Food, grew up around this kind of stuff, but I didn’t at all. I knew Ina Garten and Nigella Lawson and Bobby Flay. But I realized that what I was responding to as a kid, thinking that not eating meat was a cool or countercultural thing, was all this stuff that had come before. It had filtered its way down to me somehow through signifiers like tofu and seitan and tempeh. For me, the cultures and the political perspectives are so inextricable from the food. You could separate the food from those things but I wouldn’t want to.

It always frustrates me when I encounter people who consider themselves progressive, or alternative, or anarchic—whatever adjective you want to use—and they’re so indifferent to the politics of food. That lack of intersectionality always surprises me.

Right. It’s very stressful and upsetting to me to talk to people who supposedly have a consciousness around certain progressive issues and then think that food is completely not part of that. It drives me absolutely nuts when I’m around academic leftists who have no consciousness about where their meat comes from or the conditions of meatpacking. In the US, we’re rolling back child labour laws in order to get workers into the meat-processing industry. It’s Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle all over again.

[Those leftists] are very, very antagonized by veganism as a bourgeois consumer choice that they see as not having any real impact. I do think there’s that element to it—that people don’t see it as serious. But when you already have commitments to workers, to the environment, to feminism, and you don’t see the connections between domestic labour, farm labour, meatpacking labour, and the choices you make three times a day, that’s a real cognitive dissonance to me. It’s such an American thing. We have such a deep hatred of taking food seriously here—it’s seen as such a frivolous interest.

The book makes persuasive arguments for eating locally, eating ethically and sustainably grown food, eating less meat. But in a recent newsletter you wrote that you bristle when, in interviews, people ask you how they should eat. You say there is no one way that people should eat. I get that, but as you also argue in the book, there’s just so much at stake. You do want people to eat in a more mindful, sustainable, less corporately driven way.

It does seem incongruous. I certainly don’t want to say that everyone needs to be a vegan. Because the ecological science doesn’t bear out—we need animals in certain grazing situations, et cetera. That’s the way the world was built. But the way we do industrial animal agriculture is wildly problematic. And, obviously, in the book my argument is that anyone who can make the choice to eat differently absolutely, depending on your economic and nutritional needs, needs to make the choice to eat differently. We really don’t have any options. We have seven of the hottest days on record this week globally. We’re seeing flooding in Spain and Vermont. It’s been 90 degrees every single day for weeks here in Puerto Rico, and early in the season. The climate-resilient crops are not growing to the extent that they’re supposed to be growing. We’re at a real crisis point.

In the book, I’m trying to make a strong case that whatever your cultural traditions are, there is a way for you to eat a more plant-based diet. We didn’t always eat an industrially produced amount of meat all around the world. In the US, there’s 260 pounds of meat produced or available per person per year. This isn’t natural. This is a manufactured style of eating—the standard American diet, a Western diet built on meat. And we can manufacture a new way of eating that doesn’t have these bad impacts. So why not do that?

Yeah.

I try not to say the word “should” because there is a big overlap in the vegan community with people who have had eating disorders. There are also people who nutritionally need to consume a certain amount of meat. I’m mindful of that. I don’t want to put more pressure on folks who are just trying to get through the day in terms of their relationship to food.

How long have you been in Puerto Rico now?

Since 2019. Four years.

That’s obviously affected the way you see food and food systems. Do you think your understanding of food would have evolved like this had you stayed in Brooklyn?

I’d been visiting Puerto Rico for many years before I moved. I started to understand [food systems] a little bit, but I didn’t really understand. Now I’ll go to the farmer’s market on the weekend and we won’t have any greens because of the extreme heat. I’ll go to my husband’s grandfather’s farm and see unripe breadfruit fall to the ground because of the heat and lack of water. There are months where there are no eggs because eggs really are seasonal if you’re eating them properly.

Even though New York has such a robust farming culture, I just wasn’t as in tune with these kinds of things there. [In Puerto Rico,] all our food is imported. It’s very expensive. It’s often rotting already when it gets to the supermarket. The selection is much more limited. Obviously, in New York, I could go to a million different markets and get literally anything. I’ve had to cook a lot more since I moved here because eating out is very expensive. Because there’s not as much variety, I’ve had to learn to make Chinese or Indian dishes that in New York I would have eaten at restaurants. Folks are not making as much money but the cost of living is wildly high. I think we have the highest grocery costs in all of Latin America. It really changed my perspective on everything.

I thought I was mindful about things like food waste or water usage before, but now I’m hypervigilant about it. It’s also things like having a propane stove in a time when everyone thinks we need to move to induction and electric stoves. And it’s like, well, I want to be able to cook when the power goes out. I don’t think I would have written the book I wrote if I hadn’t moved, and experienced what it’s like to eat here on a daily basis. It’s definitely changed how I approach my writing, it’s very much deepened it. I don’t know what I would be writing if I was still in Brooklyn. My experiences were so different—and myopic too. I just didn’t have that much understanding of how most people have to eat or where they shop or things like that.

And perhaps it’s also given you a preview of the way we’ll all have to eat thirty, forty, fifty years from now.

Yeah. It sounds a little hokey to be like, “Oh, I’m grateful for it,” but I am. I’ve made intellectual arguments that Puerto Rico is on the front lines of climate change. And now I actually experience that on a regular basis.

In a chapter titled “The Future of Food,” you’re critical of food tech, and fake meats from Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods. You describe yourself as a techno-pessimist, and you write, “I always envision a dystopian time in which a vertical urban farm run by a benevolent-looking tech bro sells us subscriptions to lettuce the way we pay for Spotify…” What for you is the difference between that tech bro and, say, the farmer who sells a CSA [Community Shared Agriculture, whereby consumers purchase a share of a farm harvest in advance], in terms of their effect on the world?

The conditions in which the tech bro is selling us a lettuce subscription are that we’ve killed the soil and the air and it’s happening in a warehouse. It’s dystopian because of the conditions which would foster that, versus the conditions that would foster a farmer planting a great diversity of crops on their land in order to put nitrogen and carbon back in the soil.

My experience in Brooklyn of being among all the food tech and writing for a magazine that did a conference called “Food Loves Tech” really, really made me afraid of exactly this kind of future. It was like we were just figuring out new ways to do agribusiness that are greenwashed or virtue-washed into looking like they’re a new way of eating when what they are really preparing us for is just continued corporate ownership of food. They’re preparing us for the soil being dried out and unable to grow anything. They’re preparing us for cultivating mushrooms off our own waste using grow lights. It felt like I was being prepared for a very bad future where the Elon Musks of the world controlled the food supply.

I always bring up what’s happened with food sovereignty in Puerto Rico. Before Operation Bootstrap in the ’40s and ’50s, which was a movement to get people to do “better” manufacturing jobs in the city, 45 per cent of the workforce here was in agriculture. There was a slow degradation of the idea of the farmer as a worker. People don’t want to be farmers. Now, Monsanto (or Bayer Monsanto) owns the best farmland here. And they’re not here trying to feed everybody, they’re here doing experiments. The USDA too has a huge agricultural research arm here, because this is a tropical place, it’s very hot. These are the conditions we’re all going to exist in in the future.

Yes, exactly.

I always think of the Jones Act, too, during which the ability to grow food here, the support for growing food, was decimated. What happens during a disaster, when suddenly there is no food or all the food that’s here is going rotten? When people can’t get to each other because the roads are flooded? What does the US bring in? Processed, packaged food in a box. So I’m always thinking about what kind of world requires these things. I feel these companies are always profiting off the worst-case scenario, instead of putting resources into avoiding the worst-case scenario.

I do wonder if they want those conditions, where we are 100 per cent beholden to corporate ownership of food. I mean, I’m weirded out even by those strawberries that are grown in a factory or something. They’re like the perfect strawberry, they all look the same, and they’re in a neat little package. And everyone’s like, “Oh, these are the best strawberries, and they’re so beautiful.” Why do we need that? Why can’t we just wait for the season of strawberries? Because if we’re not taking care of the land and taking care of biodiversity, that’s what the future is. And that to me is very sad.

The book is so thorough—you talk about the history of tofu and vegan cheese, your own personal journey, wellness culture, white supremacy. It feels like it contains almost every idea you’ve had about food in the last decade. Did you set out to make it so comprehensive?

I’m happy to hear that because it’s a short book and I could have written one double the length. But I’ve been preparing to write this book for ten years, whether I knew it or not. I vacillated over doing it for a while. But after I sat down to do it, I worked really hard on the intro, and then went into a kind of depression about it for six months. I couldn’t write anything because I felt so daunted by it. I watched a lot of Netflix. When I got back into it, I went really hard for like six months to finish it. I went really, really hard at the end. I took a month off my newsletter, spent a week at my mom’s apartment over Christmas, and then came back to Puerto Rico and spent another week finishing it. I was writing 8,000 words a day—I was lit on fire to finish it. But I had already done all this thinking, and once I accepted that I wasn’t going to have a thought that would crack this open and make me write the greatest book that’s ever been written—which I think is a common worry—then I was finally able to finish it. I was able to be like, I’ve done this work and I’m ready to put it down and give it to somebody else and then give it to the world.

Being an essayist gives you the ability to process a lot of information without necessarily overwhelming the reader. So that was the way I went forward, in making it comprehensive but not overwhelming. I just approached it as a 65,000-word essay on the subject, and that was how I un-daunted myself.

You’ve said writing the book was the hardest thing you’ve ever done.

Yes, because I felt so daunted by having to say everything and say it well and convince people it was worth anything. I had a very small advance and so I had to do it without any money. I had to keep working while writing it. Which is most people. But at the same time I don’t think I was prepared for how psychologically difficult it would be to not have a stable financial situation from which to write from.

Why did you want to write a book? You have all these other platforms—the newsletter, the podcast, magazine articles, social media, teaching. What could you do in a book, or what could a book do better these other platforms couldn’t?

I really wanted to put this specific moment of time into a book. I thought that was useful. People have written tons of books about vegetarianism but they are usually a bit more academic. That’s great, but it’s not getting people where they need to be. I came to veganism and to being a food writer by baking. So I always think that the best way to convince people that they can give up meat or dairy, at least for a day or a week, is to feed them something good. That can get kind of lost in much of the vegan discourse. I think vegetarians, and I say this now obviously as a vegetarian, have done a pretty good job [discussing] food. But I feel a lot of vegan discourse is very, very grounded in animal rights and the environment. Rightfully so, but it gets to the food last, and I think, for too many people, you need to get to the food first. So that’s what I’m trying to do with this book: to show that if we take a food-first approach, this is what’s possible.