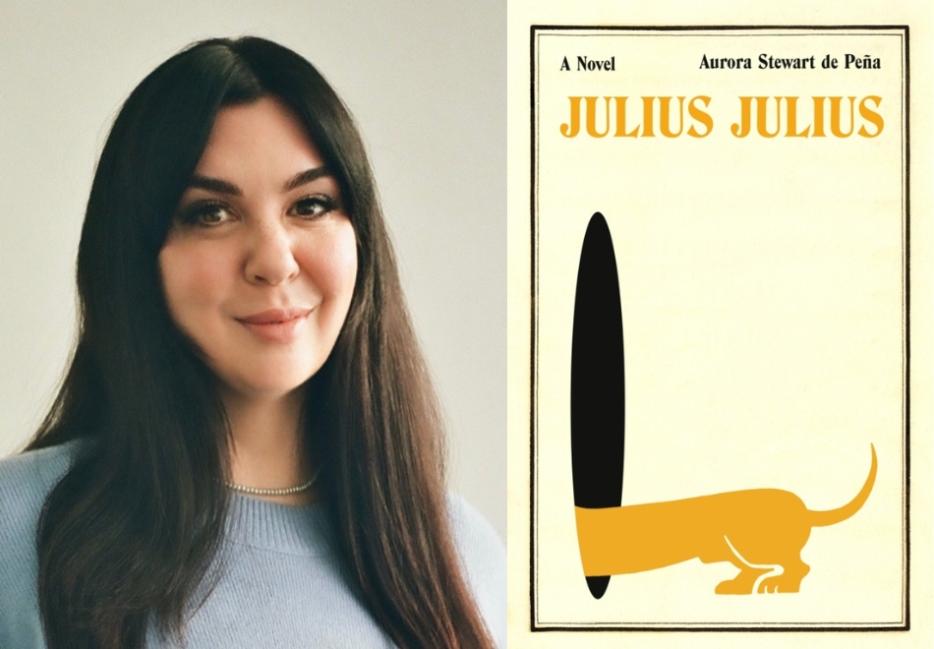

The first play I ever saw by Aurora Stewart de Peña was called 36 Little Plays About Hopeless Girls, a darkly comic carousel of, actually, thirty-three little plays about hopeless girls. The title came about when Stewart de Peña’s friend and dramaturg Chris Dupuis commented that “36” had a nicer cadence than “33.” Nearly two decades later, Stewart de Peña describes Dupuis’s edit as formative in tuning her into her own aesthetic. “Sometimes that small thing, like the title of a play or a formatting choice, will reveal more about the totality of the work,” she told me recently in advance of the release of her first novel, Julius Julius (Strange Light).

For nearly as long as she’s been a mainstay of Toronto’s independent theatre scene, Stewart de Peña has also been an in-demand advertising strategist. While her first novel has nothing to do with the theatre, it has plenty to do with the concealments and revelations of a well-employed aesthetic. This is a novel about advertising.

Populated by roaming blond sausage dogs, ghosts, and several complex mortal humans, Julius Julius satirizes the world of advertising via an ancient company known as Julius Julius, narrated by three different employees in three different eras. In the first part, an unnamed young woman navigates the agency as a Brand Anthropologist, stalked by a pervert ghost and obsessed with a misogynistic Crimean War–era women’s hygiene PSA. The second part, taking place a generation or two earlier, is narrated by the Creative Director: a self-made man who rose from tragedy to the very top of the Julius Julius food chain. In part three, a profoundly unremunerated intern—the Future Leader—navigates a lonely life at the agency after an ill-played attempt at recognition for her work. Through all three sections, Stewart de Peña’s writing is stupidly funny, intermittently tender, and coyly insightful, her fancies masking a playful but deadly seriousness.

I spoke with Stewart de Peña one clammy May day at Toronto’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Later, while walking through the current exhibition, two fashionable young patrons interrupted us to praise her gorgeous handbag. This anecdote will become relevant approximately halfway through our interview below, which has been edited and condensed (for aesthetic purposes).

*

Naomi Skwarna: Being familiar with your style of theatre, I was surprised when I learned that your first novel would be about advertising. How did that happen?

Aurora Stewart de Peña: I’ve been thinking about the difference between writing a play, which is when I hear voices conversing in my head and I have to write those down, and the novel, which felt like falling into a world and transcribing the world as best as I could. This story felt bigger and with more spaces, places, people, and times than I knew how to represent in a play. It was a way to process the enormity of what I felt working in advertising day to day, because so much of the work that we do spans decades and countries. It has the appearance of being shallow, but it never is.

I say “a book about advertising,” but it’s not entirely about advertising. It’s about this kind of Fraggle Rock–like space that is Julius Julius, and the world contained within it, which takes the form of an advertising agency. It’s not like Mad Men.

I kind of think it is! But my version of it.

Yeah, your version has caverns and ghosts and a glass ceiling that you can see the bottoms of people’s shoes through.

Scott [my husband] says it’s Mad Men if Miyazaki was doing it. Part of me also thinks I’ve written a pretty good strategy instructional if you want to learn about advertising.

It’s extremely instructive!

Did I write a business book a little bit? I don’t think it’s not a business book. I mean, yeah, it’s all those things, but it is also a representation of my feelings when I’m within an advertising agency.

Each of the three sections of the novel are narrated by extremely solitary voices: the Brand Anthropologist, the Creative Director, and the Future Leader. What inclined you to write these characters as kind of siloed within and defined by their roles at the agency?

I often felt lonely working in advertising, and the book is an investigation about how that loneliness occurs. There’s something too about being in a workspace where you’re not choosing the people around you. You’re choosing them because you accept the job, but you just have a bunch of peers, and you don’t necessarily know what their lives are like, or how connected you really can be to them, because your livelihood depends on you being a likeable person.

I was interested in the way that we put forward a version of ourselves that’s palatable to other people in a workspace—maybe other people aren’t doing this, but I certainly am—and the way that that isolates us, despite the fact that you’re putting forward a friendlier or brighter or more intellectually available–seeming persona. People are often afraid to have their full roster of feelings within a workspace, and I think that’s very isolating. That isolation is something I was really interested in.

That comes through in how you’ve structured the novel. It feels very much like these people are walking alongside each other, never meeting. All of them filter their complex emotional experiences of life at Julius Julius into their work.

The Mad Men [series finale] ended with the “I’d like to buy the world a Coke” ad, and for my whole life that ad has been tremendously meaningful and deeply confusing to me, because Coca-Cola is involved and invested in so many nefarious and violent operations. They approached this agency, McCann Erickson, which was known for their young counterculture creatives. [They found that] what we wanted to be part of, more than anything, was this beautiful expression of the youth of the world singing on a mountaintop. It’s so hopeful, and it actually makes me very emotional! But what a wild thing to be able to harness that impulse and redirect it towards Coke. It’s fucked. And it worked. It works! So, people are taking that impulse, because it’s got to come out somewhere, and pouring it into their work.

The Brand Anthropologist seems like someone who really buys into and expounds on the power of advertising. Her section of the novel is full of so many slogans and arguments on its behalf. But then there are these little slippages, where it seems she may feel more than she lets on, like the section where she describes the smell of fresh plastic toys eventually smelling like mildew. Advertising can’t live in the real world.

Well, the advertising is ephemeral, and I would say perpetual. But the products that it’s selling are just hunks of plastic.

You don’t think that taints the advertising as well?

No, because we still perpetually buy new things. We don’t learn from it. Maybe there are people who the capitalism isn’t working on. I’m certainly not one of them. I’m aware of what’s being done and what’s being said, and I know that after I buy this fancy purse or new skirt, it’s going to end up on my floor like everything else. But that doesn’t stop me from being like, “Oh, look at that woman walking in an art gallery in the city in a fashion spread. That could be me, and it will be when I get this outfit.”

You can suspend your disbelief?

I can suspend my disbelief. I think the whole book, and particularly that portion that you’re talking about, was reconciling my reckless optimism with the skepticism of capitalism that my parents raised me to have—which made me sort of unemployable. When I figured out that I could work somewhere and earn a steady paycheque, I think I really was quite naive about what this work was and what it did. Writing the book, I was coming back around to the fact that these systems can be really harmful—that maybe the tool of advertising is neutral, but it’s not applied neutrally.

And that Coke ad seems like a—

Glittering example of that idea.

But you admire the, I don’t know what would you call it, the art?

The execution. I will watch a piece, recognize the mechanisms, and still feel an emotional stir, like, “They did it again.” It works every time. I think [the novel] is me coming to terms with feelings versus logic—of being brought to the precipice of a world and wanting to step in while also knowing the mechanisms at work. When you talk about slippages, that’s what I was beginning to feel when I wrote the book.

The question of loneliness in the workplace really comes across in the Brand Anthropologist’s experience of being sexually harassed and stalked by a ghost, formerly an executive at Julius Julius. Why is he a ghost?

Oh, because you can’t get rid of him! He’s an institutional problem. I’ve had to report sexual harassment at almost every place I’ve worked, and the response has been good only a couple of times. Most of the time they’re like, “Oh my God, no, really, wow. Did he mean to? Do you think he meant it? You know, he is really close with the CEO.” It feels like black mould. Old, institutional. Built into the foundation.

It’s hard for the Brand Anthropologist to put her finger on. He offers slightly inscrutable traces of himself: moving things around on her desk; leaving deodorant and bars of used Irish Spring soap. She can’t point to anything really incriminating.

It can seem sort of diaphanous. It’s often many interactions over a series of years. Sometimes it’s a vibe, like someone romanticizing or sexualizing an atmosphere for years, and you sound totally nuts being like, “Well, he often talked about the ways in which he would have sex with his wife at work meetings, and then compare me to her, physically.” It just doesn’t ever feel quite tangible enough. Making [the harasser] a ghost was a conscious decision.

The stalking element is particularly eerie: her lack of privacy, since he is literally diaphanous.

Yeah, like, “He left deodorant on my desk.” It seems like nothing, but, like, I apply that to my armpits. It’s called Secret. You’re just in an owned atmosphere, and it’s not yours.

Related to this contextual loneliness is the spectre of a character’s likeability. You had mentioned earlier bringing a more easily likeable persona to the workplace. How does likeability relate to your characters, and what does it have to do with advertising?

In advertising, likeability is everything. No one wants you if you’re not a likeable person, because you’re selling ideas, you’re selling products. It is a business of relationships. Even if you think about Mad Men, Don Draper’s not always likeable, but he’s very, very good looking, and people like that. In that world, there are a lot of conventionally attractive, charming people who have worked at being both of those things. You are selling yourself as a talented part of the agency, and you’re selling ideas. People liking you is everything.

I was not qualified to work in advertising at all, but I think that I seemed likeable when I walked in. I’m not trying to undermine any accomplishments, but I think there are many writers just as talented as me who don’t have a Hunger Games, reality competition–style desire to be liked the way that I do. I think it’s really hard to get by as an unlikeable person in advertising. You have to have something that people are attracted to, whether you are charming or you come across as sort of performatively brilliant. You always have to seem, in my experience, like someone people would want to be.

Something that I associate with your writing is this very playful approach to inventing products and businesses—and what I might call ephemera. One of the real standouts in Julius Julius is the Wash Up, Lasses! campaign, which you detail so lovingly.

I’ve always related to the character of Dudley in The Royal Tenenbaums, the kid that notices the little dents in things. There are little worlds to be found in all kinds of things. The work of making advertising is the work of making little worlds and enticing people to step into them over and over.

Was Wash Up, Lasses! inspired by any particular ad campaigns?

It comes from a tradition of advertising that builds consensus and shifts behaviour—PSAs, like Uncle Sam and Rosie the Riveter. I was trying to get at the way that so much of the way we operate in the world has been dictated to us by agencies and corporations. I wrote that part during COVID when all of the twenty-second handwashing things happened. I was thinking about how future generations are going to know that [singing] “Happy Birthday” is the correct amount of time to wash hands, but they won’t know that it was an ad campaign. Not driving drunk was an ad campaign. A lot of big and little ways that we behave come from ad campaigns.

I made up Wash Up, Lasses! for the book, but I’ve always been so insulted by ads in restaurant washrooms that say, “Staff must wash their hands.” They know that, who do you think is working here? Why do you think that the staff need a sign? It’s not for the staff. It’s for everyone to know that the staff are washing their hands after they use the washroom. It’s such a drippy, shaming way to do it, but it works.

What I love about the way the Brand Anthropologist keeps coming back to Wash Up, Lasses! is that while it’s seen as an archival ad campaign promoting hygiene, it actually suggests something much darker about misogyny and the threat of female sexuality.

It was Florence Nightingale who walked into a filth-covered hospital during the Crimean War. She described people lying in their own excrement, beds crawling with lice and bedbugs and vermin. In her nursing practice, she was like, “Maybe if we tried to apply some simple hygiene,” and was responsible for so much popular knowledge about germ theory. But the way that women have been advertised to for the entire time that we’ve had ad agencies has been as though we’re dirty. It was a reflection of that deeply damaging, frustrating, and condescending idea.

Like what you said about singing “Happy Birthday” while washing our hands—the advertiser gets to slip away.

One hundred percent, and what’s left is the message. I think that’s really the thing with all advertising. You have these messages with the context removed. And, of course, the context is everything. That’s always been disturbing to me—this message coming down from the authorities. These are people from this specific place in this specific world, and their perspective is never addressed. We just receive their messages.

Let’s discuss the formatting in Julius Julius! There’s lots of emphatic space that highlights transitions, with turned pages revealing a new thought or an addendum to the previous one. How did you come to this style of formatting?

Maybe it’s growing up reading theatre and poetry, but a thought needs space around it. It allows for the reader to have more of their brain in the book.

It felt like one of the indications to me that the novel was written by a playwright.

I also think it’s an indication of it being written by an advertiser. You have to be so concise all the time, and there’s so much thought about where your eye is drawn, and what you’re allowed to think of when you’re looking at, for instance, a billboard with a line on it. Space is used in that way too, so that you’re allowed to process the thought on its own.

There’s a really nice rhythm to the reading, which I had attributed to your theatre brain, but I do see what you mean about the connection to advertising and copywriting.

Six of one, half a dozen of the other! I think both [advertising and theatre] ask you to consider the impact on the receiver of the work. In advertising, you’re trying to give people an answer to something. I always say, in advertising, you hope to leave people with answers. In theatre and in art, you want to leave people with questions, or their own thoughts. In advertising, the mechanism for getting there is short, concise writing. Right now, I think that’s what they have in common. That, and the consideration of an idea to its conclusion. I leave a lot of space for people to have their own thoughts here, and I feel the need to do that, both in advertising and theatre, because people need to hear it and have a takeaway. I’m interested to see what happens when I’m out of advertising for a bit, and maybe I don’t feel so bound to that way of using language.