Like many trans creatives of our generation, Torrey Peters and I have existed in one-degree of separation for years. But up until this conversation, we had never formally connected. My familiarity with her was rooted in a combination of many shared friends and the impact of her 2021 debut novel, Detransition, Baby, which took the literary world by storm and ushered in a moment of mainstream trans representational possibility that few thought possible. Her characters were sharp, inconsistent, flawed and often failing, rebuking turns toward respectability politics and trans normativity that many feared were suffocating the potential for boundary-pushing creativity.

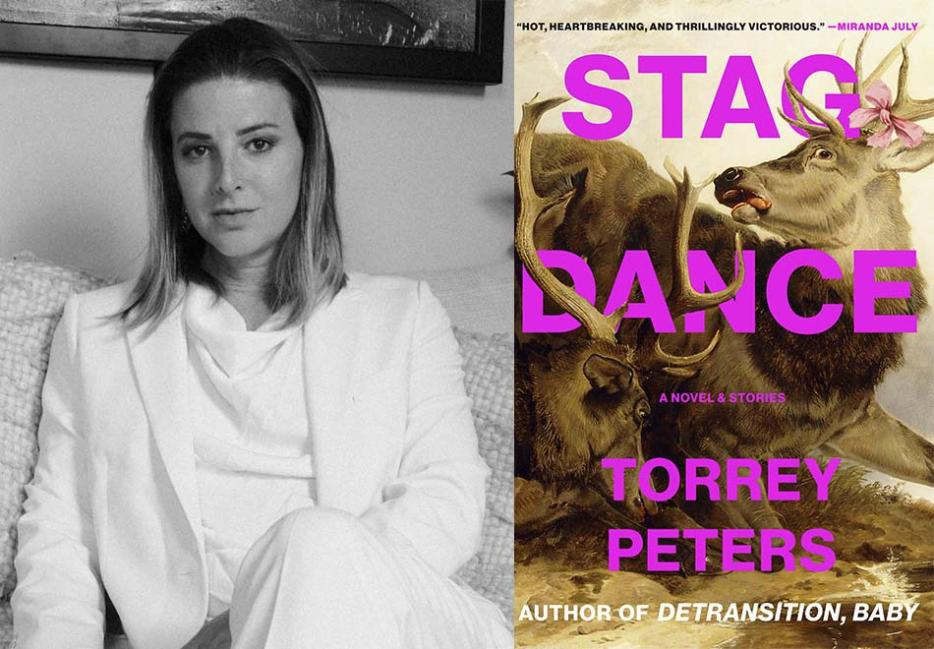

In March 2025, I attended the Los Angeles launch for her second book, Stag Dance (Random House), but left without introducing myself—the line was long— something I had to admit to Torrey at the top of our conversation.

Chase Joynt: I’d like to start by asking you about something that happened in LA. I was taken aback—and admittedly enraptured—by a simple, but striking question. A trans person in the crowd took the mic and said, quite pointedly, “Do you like being trans?” What did you make of that question?

Torrey Peters: Well, you're going catch me now because I don't remember how I answered it; I think I said “Yes, full stop, next question.” And then jokingly went back. So, here's how I'm going to try and interpret it now: I think that a lot of the trans stories in this book are not stories of positive representation, and that people might read this book and basically be like, “Do you not like other trans women? Do you not like trans people? Do you wish you were cis?” or something like that.

[In LA,] I was sitting next to Alyssa Nutting, who I really love and admire, and so I was probably trying to be funny for the sake of Alyssa, to impress her. But for you, I'm not going to try and be funny. Now I know you didn't stay in the signing line; I'm not going to extend myself with humour. [Both laughing]

Very fair! I can take it.

I think that person was just like “What's going on? Because of the tenor of these stories. . .” You know, for me, what is oftentimes interesting in writing trans stories, and what's useful in my life with other trans people, isn't just positive role models, positive reputation, positive representation, but allowing for negative role models for each other. I think trans culture is about sharing experiences with one another, sharing ideas, sharing art. And the way you get better—or the way you make your life easier—the way the culture evolves, is you don't just emulate what works. You also spend a lot of time avoiding what does not work. I’m grateful for the people who came before me, not only for their victories, which certainly get celebrated, but I’m grateful for their fuckups. Because if I pay enough attention to the trans people who came before me, maybe I won’t have to repeat some of those extremely painful fuckups that they lived through. And so, that is in my stories. I don’t think that erasing that stuff does anybody any favors, because maybe even you don’t have to live with people who are fucking up. You can just read my stories and avoid the fuckups.

And if you're reading fiction, what you want is tension. You want the same richness of story that you get in—whatever, I’ll just go ahead and compare myself to Tolstoy, picking an author out of a hat. In a Tolstoy story, there's drama, there's intrigue, there's gossip, there's betrayal, there's cruelty, there's backstabbing. And why is the story so rich? Because it has all the stuff of human life. And that's what I want in a trans experience too. You know, if I'm a trans, if I'm writing trans fiction, and I've got some juicy betrayals, some cruelty, and other things that make for great stories, I'm not going to pass that by just so that people can say, “Hey, this was a really uplifting story of a trans person,” you know?

Absolutely. In reading your work, I was reminded of how fiction is a provocative way to get closer to the truth of things, and how fiction becomes a way to open to the complexities of ambivalence and desire that constitute much of trans life—especially for those of us who've been transitioned for a long time. This idea is connected to one of my favorite lines in the book’s acknowledgements, where you say something to the effect of: “I'm using genre as a way to work out the ongoing inconvenience of my never-ending transition.” Can you say more about that? I immediately resonated with this and am excited by it as a motivation for method.

I think that there's a telos to transition; where you start, and there's a before, and there's an after, and in these stories, I'm taking on different aspects of that. The stories are about the things that transition creates for you.

Stag Dance is a story of this lumberjack named Babe Bunyan, who's the biggest, strongest axe man, but who considers himself very ugly. He's working at a winter logging camp where they're illegally cutting trees to get them out before spring. And they're lonely so they throw a stag dance, which was something I learned from this book called Re-dressing America's Frontier Past by Peter Boag. What happens at a stag dance is that some of the men cut out little triangles of fabric, maybe the hypotenuse of three inches, and hang it upside down in front of their crotch. This indicates that they want to dance as women. For me, that is the barest symbol of transition—like if transition is always a series of symbols that you sort of adopt to negotiate your gender with the world, it's the most stripped-down symbol you could possibly imagine. Babe Bunyan decides he's going to wear the triangle for the dance, and he ends up in this rivalry with Lisen who is the prettiest, twink-iest member of camp. One of the things I was looking at is the way that Lisen's transition is super easy; all Lisen has to do is wear the triangle and people are like, “Great you're a girl now, we want to dance with you,” whereas Babe Bunyan wears a triangle and nobody believes that. Nobody's like, you're a girl now. They refuse to give that to him. And that's sort of just the accident of their bodies.

You know, the party line is “All you have to do is if you want to transition, you just have to transition” but in fact, transition isn't fair and we're all given certain bodies where we have certain backgrounds, we're raised certain ways, we have certain amounts of money. For one person, transition might be two steps, for somebody else it might be twenty steps, and they are still constantly having to negotiate the fact that they have transitioned with the world as they move through it. And the idea that it's at all fair or that it can ever really end or that it will end for this person but not that person. . . all of it is unfair. All of it produces a kind of discontent on the easy end, and misery on the far end. And these are uncomfortable topics. Between me and somebody who you might say is my sister as a trans woman, there is that unevenness, there's that unfairness, and even 10 years later, those resentments still exist for me. And for me as a fiction writer, that stuff is actually very, very rich. It's the fact that it's not perfect, the fact that it's contradictory and unevenly distributed.

I really love that. There were many moments while reading where I wanted to ask you about the interiority of folks in the stories, and the modes of externalization that you engage, like the triangle. It made me think about early trans life and those moments where you attach to that one thing, maybe even just a feeling, and think, “Holy shit, I'm doing it! I'm doing something that matters deeply to me and I don't really care what you think.” But then other times when you're desperate for someone else to see the thing, to recognize it and to validate you through that externalization. I feel like those tensions are so beautiful and brilliant throughout the book. There is also something compelling to me about what you anticipate your reader knowing and what you do not allow your characters to know, and the collision between those modes of knowing or those ways of intuiting. It produces exciting tension in the stories because you can't help but want the characters to move in a certain way even while they're not, because you can see around them in ways that they can't see themselves—it's dynamic as a reading experience.

I started Stag Dance as an audiobook on a plane and finished reading it on the page, the varied experience of which leads me to a question about voice. Can you talk me through some of your choices about your various authorial voices?

The first two stories I wrote are the voices that are closest to my voice, “The Masker” and “Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones.” I was writing them in 2015–16, and by the time I finished Detransition, Baby, I had developed a sort of catty voice with Reese that was more fun for me than the voice that was closer to my own. When I started writing “The Chaser” people were like, “Why did you choose to write the perspective of a bro cis guy?” And I have a series of things that I say to that: I think transness is not very other and that, in fact, cis guys are experiencing the kind of emotional building blocks of transness. They are just two different ends of that spectrum. Take the narrator of that story, for instance. The distance between how he feels and how he wants to be seen by the world, that distance is kind of a trans distance. The distance between his body and his desires, the way that shame informs all that stuff, those are things that trans people feel. It doesn’t make him want to transition, but the discomfort that goads him into doing things, is the same kind of goading that I think I felt, and that led me to call myself trans.

Some people are like, “I could never understand the trans experience,” but you are already feeling it. It drives you to do something different than what it drives me to do, but you're already acting out of the same things that are causing me to act. And so, I was like well, I'm going to write that perspective partially from his perspective to show that aspect, but also because I just think it'd be fun to write as a bro and to do a genre thing, because it was fun and it made me laugh.

Similarly, when I started writing “Stag Dance” I came to the setting somewhat organically. I was building a sauna in the woods. I was thinking about trees and building because I had to cut down a bunch of trees for firewood and to build the sauna, and I was thinking about my gender when I was alone in the woods. I thought, “Why did I transition just to end up stoically building a building?” My 17-year-old self would be like “Oh look at you alone in the woods, proud of your proficiency with tools, like why the fuck did you bother with this transition?” You know? I had some feelings about that and thought maybe I'll play with this.

I'd be curious what you think; as a nonfiction writer right now, especially with trans issues. If I go to somebody and I say, ”Trans people should be respected,” something just as basic as that, or “Trans rights are important,” nobody hears me because everybody already has their own talking points, their own treatises, their own intellectual apparatus that they're wielding as a shield in front of them, and oftentimes you can't penetrate it. I'm attempting to get around that shield, to come in from the side where even though the reader has that big shield of intellectual apparatus, they're just feeling things then they're sort of rebuilding. I was thinking about during the 60s when Americans were so polarized about their opinions about the Vietnam War that they couldn't hear each other. And how that was the moment of the rise of new journalism, where even journalists were like, “We're not going to give you facts anymore. We're just going to give you you know, Didions out here doing the Didion thing.” Tom Wolfe is creating these strange narratives of acid takers. And it's all novelistic details. It's all emotive. It's all this kind of stuff because, the intellectual approach or approaching something through the intellect was so. . . barnacled over with this kind of stuff that you couldn't actually touch anything. So that's how I feel about trans issues. That I actually can't talk to anybody about trans issues. I can only just try and make them feel things.

One of my favorite scenes to read is a sex scene around that triangle that we discussed earlier. And the way that the triangle functions as a prosthesis and a body I think is very much a trans preoccupation; how do you make your body into the body you want, to be using your own will and the material world. But saying something like prosthesis and appendage theory or all this sort of stuff, it's like a needle scratch in fiction. I mean, not all fiction, but my type of fiction. And so, rewriting it in logger slang, it defamiliarized it. It made me almost experience it trying to figure out how to talk about this stuff. It was as though I was talking about it for the very first time. And in talking about it for the very first time, I was really thinking it anew. And it became anew to me.

That response sets up my next question, which is more explicitly about your imagination and deployment of sex in the book. You know, everyone is talking about the Miranda July All Fours tampon scene as a sex scene of the year, and I feel like you are giving her a run for her money in Stag Dance. You are offering a platform for us to consider sex as it relates to transness and trans becoming, and I would love to hear you talk more about its centrality to the project.

I think it has to do a lot with this moment where for the past 20–30 years, for reasons of respectability politics and acceptance—and just to have people understand stuff—the general line was “Oh, sex and gender, or sexuality and gender, are separate things.” And now it's like, “No, actually, you can kind of discover your gender through sex.” That those things are separated is largely just to not make people uncomfortable, you know? It’s not just about trans people. Everybody is discovering their gender through sex.

If you look at that Miranda July book, part of what's interesting is that she's doing trans love, where she's discovering her gender through the sex. What kind of woman do I want to be? Do I want to be a wife? It is the sex that is teaching her, not to procreate, but what kind of person she wants to be. And that's what trans people are doing. They're having sex to figure out what kind of people they want to be. And so, the fun thing about writing trans sex is that we have already been figuring this out for a long time, so we're ahead. If everybody's trying to figure this out, and this is the moment in which the rest of the world figures out, “Oh, you don't just have sex because you want somebody, it's that you have sex to figure out who you want to be.” If that's the thing that the rest of the world is figuring out, we've got a 10–20-year head start on that, despite our obfuscations towards respectability. So, I feel like we're well positioned to write sex in this moment. And on top of it, sex scenes are best when they're fraught, I think. Or in fiction. Erotica can just be hot sex scenes. But in fiction, I think that when there's real stakes in a sex scene—I'm not saying that you can’t just have a sex scene because you want to have a sex scene. I'm not prescriptive about sex scenes, but I think that when trans people are finally getting to have sex that allows them to be the person that they want to be, which has been forbidden to them, there's real stakes. I would say that the kind of sex that trans people are having are—in the context of society—often dangerous. And so, you have narrative tension just by the act of trans people having sex, rather than by having to sort of figure out a context in which sex can be dangerous. That is all to the benefit, strangely. It's to the hindrance of living as a trans person, but it is to the benefit of writing trans fiction.

Yes. One of the ways that I would join you in that conversation is to say it's about the concurrent tracks we live: both the insidiousness and impact of transphobia and the role of desire in our self-becoming. Throughout the book, but in “Stag Dance” in a very particular way, you are asking us to consider how desire and sex relate to trans subjectivities. And I think your assertion that writing sex reveals us to be 10–20 years ahead in this conversation is so compelling. And it relates to an earlier part of our conversation where we spoke about genre as a way to have conversations that we’re not otherwise having. But I also know that this is the stuff we talk about to each other behind the scenes. This is the stuff we're having conversations about with our friends and it begs the question, how do we have these conversations in public? And it strikes me that writing sex is a critical tool of trans becoming and a potentially transformative gesture that can impact, for the better, conversations about representation and good politics etc.

I think that's very well said, and I know there's a lot of us doing it, I don't want to say I'm the only one doing it. It becomes more compelling too as a mosaic filled with a lot of different works, including works that are using trans ways of being without even necessarily being trans. Part of the way that All Fours is good is that Miranda July is attuned to this stuff and showing that character breaking things in a sort of trans way, and that's actually what makes the character so compelling. I have a sense of Miranda July as aware of that.

Yes, exactly. I resonate with your reading of the scene. And I think it's why it sparked for me as a compelling conversation to have alongside what you're doing, because it felt—I don't know if I would have articulated it as trans in the way that you are, but now that I hear you, I think it's right—it felt trans to me.

They're both literally prosthesis things, right? The tampon becomes a prosthesis.

Yes. And there's a stillness of approach. You know, people often imagine things—from transition to desire—to emerge in a flurry, and sometimes the most significant experiences are actually very quiet and quite still. And it's in that stillness where you learn something important about how you feel. And this question of how one feels is central to your writing. There is often a desperation in your characters to express how they feel, and even more importantly, to be seen, validated, held and loved for those feelings. And I wonder if there is a version of this question that applies to you as the author of a book of this kind, emerging into the world in this moment? What do you want us to know about how you feel?

I mean, I guess. . . This is a really hard question for me, which is obviously why I'm hesitating on it. But I think if you look at the evolution of my writing, something that has gotten more and more important to me is tone. I think the early stories, they're kind of punk. They can be unsettling, but they're not super attuned to tone. Let me try to answer this question differently. . . . The thing is,: what do I want people to know about how I feel as a trans person or as Torrey Peters? Torrey Peters, the person, not the author? I have a lot to say about that. I have a lot of opinions about politics at this moment. I'm angry. I'm disgusted. In some ways, I'm invigorated. And I want people to join me in feeling invigorated in this moment. When people ask me, “Why are trans people at the center of this political moment?” I think the reason that everybody's obsessed with us, like I was saying about the sex thing, is that we're doing something that's necessary and they're scared of it. They're not just like, “Oh, trans people are over there.” What's happening is trans people are doing things now that other people recognize in themselves. And that's why, as far as I can tell, we're at the centre of things. It's like, well, maybe if crypto is made up, maybe a bunch of other things are made up, and who is talking about that in ways that make us uncomfortable? Well, trans people. And so, this is a strange opportunity because there's so much attention, so much focus on us, and I think we're making better art. I think we're telling better stories. I think our worldview is more compelling. I think that there's something very seductive about what we're doing. And that's what's scary about us. So, I'm feeling fired up. I'm feeling intrepid. I'm feeling infuriated. All these things, as a person.

As an artist, though, I feel like, to handle the complexity of all that stuff, I must do emotion first. I can’t say any of that stuff that I just said so directly in talking to you as a person. I must find other ways to communicate it in art, because everybody has these blocks on the intellectual side. So, I'm almost translating the ways that I'm feeling into a series of tones and trying to work with tones. And the more I am working with tones, the more effective I feel. Stag Dance is as much an exercise in tone as it is in language. And it’s the tone that's effective. And that's the kind of thing I want to put out as an artist. Like, oh, you know, this feeling? You know, this tone? Here it is. Let it just resonate with you. Here's a fun yarn, like a fun dark yarn, let that resonate with you.