Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation (Penguin Press) tells the story of a young woman who lives a mostly empty life. Living off unemployment cheques and her inheritance following the death of her parents, she decides to spend an entire year in a drug induced slumber. Guided by her pill pushing, extremely irresponsible psychiatrist who believes her to be an anxiety ridden insomniac, she shuts out the world behind her and escapes. As her drug cocktails become increasingly complex, the unnamed protagonist’s experiment doesn’t go as planned. The young woman finds herself living a parallel life she can’t control or understand.

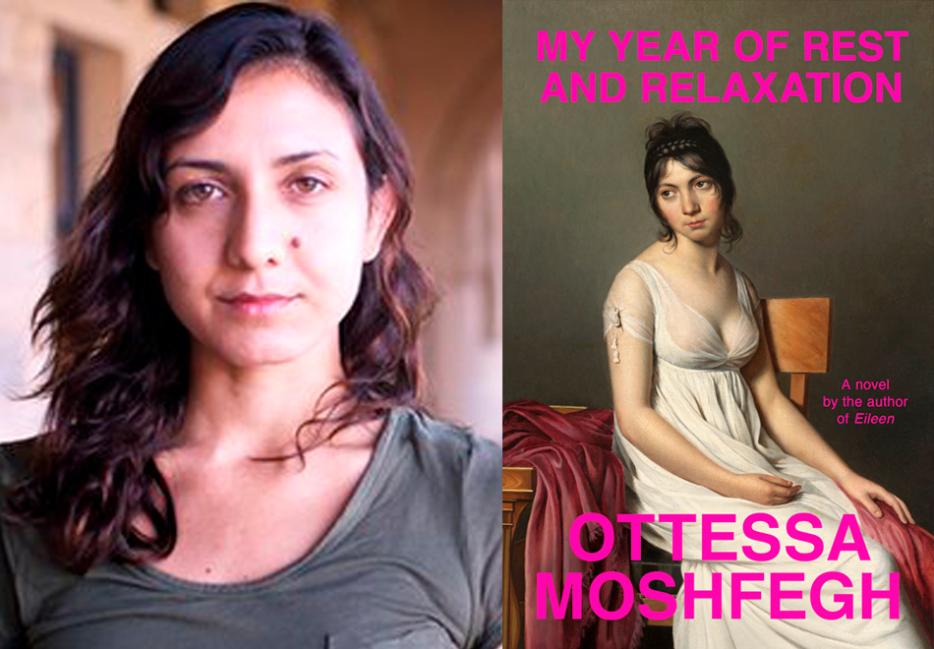

Moshfegh’s first novel, Eileen, faced some criticism for its portrayal of an unlikeable woman, wrapped up in self-loathing; My Year of Rest and Relaxation's portrait of a complicated woman can feel at times almost like response to such readings of that earlier work.

Sarah Hagi: I always joke that it’d be so nice to go into a harmless coma just to escape life for a moment. I’m wondering what made you come up with this as a concept for an entire novel.

Otessa Moshfegh: I can’t really point to any one line of thinking or inspiration. It really just started out sketching this character who had this habitual shuffling down to the bodega, watching movies, but having a really small life. And then consequently her whole personality and character. I don’t remember thinking, “It’d be nice to sleep for a year.”

How was it developing a character who’s asleep for most of the story?

That was a part of the fun and the challenge in figuring out how to write the book. The one plot move that is made in the book has to do with one of the medications that she gets prescribed which allows her to live a somewhat double life that she isn’t aware of. Under the influence of that drug she seems to be setting things up for herself in a way that she wouldn’t in her regular state of mind.

I think also the character Reva, and what Reva brings up for her, particularly her mother’s death, the protagonist has to revisit the death of her own parents.

I feel like every woman has had a friend like Reva, a relationship where you feel like you’re kind of stuck with someone because you’re connected through a shared history. What was it like exploring that?

I really liked writing Reva. She expressed so much of what the protagonist couldn’t. As much as Reva is someone who’s in denial and pretentious, she’s also very expressive and communicative. I think there’s some familial resonance there, in that the protagonist has no family. And in the way that your mom could walk into your room as a kid and start picking up your stuff off the floor and you’re like, “Mom, leave me alone!” There’s some of that in Reva and the protagonist’s relationship. Reva is a little bit maternal and the protagonist is sort of loathe to admit that Reva is important to her.

The book takes place in the year 2000 going into 2001, so the reader feels 9/11 looming. It’s not a 9/11 book, but the year it takes place feels very specific. Why did you make that choice?

I didn’t initially understand that I was writing a book that took place in the year before 9/11. But, it was really through the writing about the New York arts scene through the lens of the protagonist that I understood the New York in the book was the New York at the turn of the millennium. I was like, “OK, she’s sleeping for a year, that means September 11th is coming.” That was when I understood the end of the book. It usually happens to me that I’m writing a novel that I have an end image, or sensation and I know what I’m writing towards and that happened with 9/11 with this book. It was a gift because so much of this book required adopting an attitude of cynicism and juvenile angst. I felt that I needed something really deep and important to ground me in the novel because I knew where I was going. And so it wasn’t by accident that I ended up writing a book that could be put in this category of literature of 9/11.

The book is so funny, but grief is woven into the plot in a unique way using various flashbacks—what was that like to write?

It was probably naïve because up until that point. I had lost my grandparents and a close friend from childhood but I don’t think I understood grief as well as I do now. Since finishing this book I lost one of my best friends and my brother. It’s a completely different reality I’m living in than the one I was in writing a year ago. I think that’s good because I don’t think I could’ve written the book with the light touch that it needed because my own grief would have gotten in the way. It’s much easier to write fictional grief when you’re not projecting. I was certainly thinking about my own sadness and trying to tap into it when I was writing those parts. In reflection it does not compare to the experience of losing a parent or someone close to you.

When I think about my own experiences with grief, it’s difficult to know how to deal with it, but I do understand wanting to sleep through it.

There’s so much of life and healing that I think our consciousness fucks up for us. I think the body is a lot smarter than the mind. I think that was part of the principle of the protagonist functioning on, “my body will know what to do, I need to just stop thinking so much, I need to stop agitating myself with my own consciousness. That’s good reason to make myself asleep.”

A lot of things can be processed subconsciously in sleep, but the extreme measure that this protagonist takes with drugs…I didn’t want this to be a druggy book, but it was also quite evident that the way to get through something is to get through it and not drugging yourself through it. All that shit will be there when you’re sober and wake up, it’s still there.

Something that comes up a lot is how beautiful she is, and in a way it shields her. Do you think that helps her get away with her experiment?

Maybe. She probably doesn’t have the same concerns other women in their twenties might have. I think more than anything, her beauty is something that has alienated her from people. And I think there’s a thing where we don’t like feeling sorry for people with privilege. Like, “Boo hoo, you’re too pretty.” I was thinking, how do I feel about people who fit that stereotype, tall, thin, pretty and who look like models? The thing I project on them is first of all, I resent you. And second of all, you probably don’t understand what it’s like for everyone else that you’ve been treated so specially. Maybe it’s true that people who are beautiful do subconsciously from everybody else get very different kind of attention. I would imagine when things go wrong it’s very confusing.

There was controversy with Eileen because of how the character was portrayed as “ugly” and self-loathing.

I think people don’t want to talk about how big a role beauty plays in every single person’s life. In a way, I made a decision to make this character beautiful partly in response to the reception of Eileen. If I’m going to have a woman narrating her inner monologue, [she] is going to be thinking about the way she looks and picking herself apart at times if she’s remotely normal. Maybe Eileen was an extreme version of that, but I was so annoyed at the response to Eileen. People were so shocked that a young woman could have these kinds of issues when actually this feels like everyone I’ve ever known [who] at some point in high school has gone through an intense period of self-scrutiny and insecurity. So it’s like, I’m going to write an equally complicated female character but make her look like Claudia Schiffer so nobody could make a big deal about the way that she looks as though it’s part of her value. I guess the truth is that it’s always a part of someone’s value. I’m talking as much about this character being beautiful as I did talk about Eileen being disgusting.