Laura van den Berg’s stories frequently toe the line of the uncanny—the landmarks are all recognizable, but something feels off, like the tension built up by the droll repetition of the daily grind is about to break into a nightmare beyond imagining. Though van den Berg now lives in Massachusetts, the hopelessly humid atmospheres of these stories seem more suited to the Florida climate where she was born and raised.

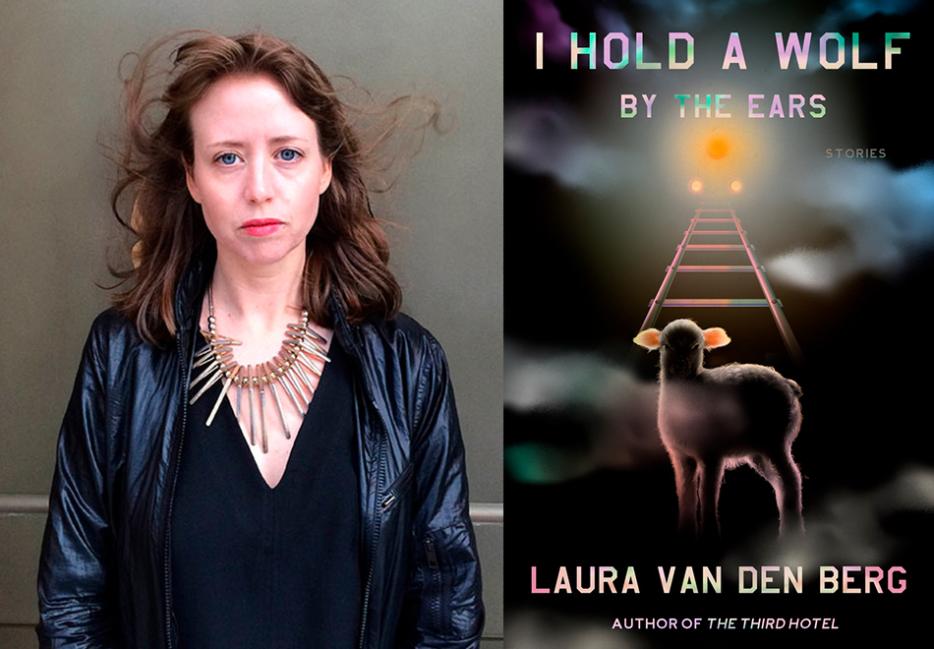

Van den Berg’s last book was a surreal-literary remix of a pulp mystery, The Third Hotel, a meditation on grief, slasher movies, and marital landscapes. Her latest work, I Hold a Wolf by the Ears (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) is a short story collection that bounces between Italy and Iceland, Mexico and Florida. A woman abruptly begins pretending to be her sister while travelling abroad. An artist becomes suspicious that her husband has been lying about his upbringing. A photographer notices something odd in the corner of photos she’s taken. Its weighted, packed-to-bursting prose invites inquisitive readers to explore the dark depths between its spines.

Nour Abi-Nakhoul: After your success with The Third Hotel, you return to the short story collection. It’s been referred to as a homecoming of sorts. Did it feel this way to you?

Laura van den Berg: Lots of writers move back and forth between the story and the novel, and some writers start with stories and then go on to exclusively write novels. I love the novel. It’s a very separate form than the story, and I love all the ways in which it is very different from a short story. But the short story is the first form of literature that I ever fell in love with. Reading short fiction made me want to be a reader, which made it possible for me to be a writer.

For reasons both artistic and deeply personal, it's a form that's super close to my heart. I can't imagine an artistic practice without the short story having a place in it. A common trajectory is debuting with a collection of stories and then following up with a novel, but I published two collections before I published a novel. In that way, it can feel like going back home.

Was it difficult to write a novel? Did you have this drive to turn to short stories instead?

It was incredibly difficult to write my first novel and it took quite a bit of time, but I knew that it was going to be a novel if it was going to be anything. It felt like a dystopian novel with many moving parts in terms of plot, with more material than can be held by the scope of a short story. The issue was that I was approaching the novel as though it was a short story; I was working on it and revising it in the way that I would if it was a short story. It took me a while to really reimagine my process essentially with a novelistic scope instead of a short story scope.

One of my teachers said he felt that a short story was closer to poem than it was to a novel. At the time I really didn't understand what that meant, because I was thinking of it in terms of verse in contrast with prose. But when I attempted a novel, I understood it. There’s a deep compression inherent to the short story, and I think that's true even in long, capacious stories. A story needs to be uncorked a bit to be a novel, and it took me quite a while to figure out how to do that.

You’ve been very public lately in your affinity for boxing. The sport was, however, notably absent from I Hold a Wolf by the Ears.

I am working on a project now that involves boxing. For a long time, I would talk to friends who are writers about boxing and they’d advise me to write about it. But I wanted to have something completely separate from writing, I didn’t want it to be contaminated by turning it into an artistic project.

But at this point I spend so much time in that world that it has inevitably leaked over into my writing. I started in the first place because I was seeing a therapist for an anxiety disorder, and the therapist told me that I needed a hobby. I ultimately ended up at a boxing gym with no background in the sport, and no athletic background at all. A few years ago, walking was a sport to me.

I started from the ground up. For my first couple of group classes, everyone else was so much more advanced—they were doing all these cool exercises, and I was literally just walking forward, backward, left, and right for an hour. Had this happened at a different time I think I would’ve found it very frustrating and tedious, but it was a particular kind of tedious that made me think of revising a sentence over and over again. After the first couple of classes when I left the gym, I would feel calmer than I’d felt in years. Boxing helped me start sleeping again, and helped me get my anxiety under control. It’s a deeply challenging sport; you have to have patience and decisiveness and it humbles you. These things have helped me as a person and implicitly help my writing practice. I also hydrate now in a way that I didn’t used to.

Can you tell me about some forms of media that had bearing on the stories in this collection?

I think of the collection as a gathering of ghost stories. In some stories that ghost is literal, like in "Slumberland," and in others the haunting is more abstract in nature. A lot of the contemporary practitioners of the ghost story and of haunted literature are near and dear to my heart. For me what is so compelling about haunted literature is that it can be a powerful medium for looking at the ignored, the repressed, the unspoken, the unseen and unacknowledged. I'm interested in how the movement of these kinds of stories can compel characters to look in directions that they are disinclined to look at on their own.

I love Julio Cortazar’s short story “House Taken Over,” which is in many ways an archetypal haunted house story. I love Mariana Enriquez’s story “Adela’s House,” which is another haunted house story. In different ways, both stories deal with landscape and structure, history and hauntedness in beautiful and powerful ways. I admire Carmen Maria Machado’s story “The Husband Stitch.” There are a couple of ghost stories in Helen Oyeyemi’s collection What is Not Yours is Not Yours that I thought about quite a bit while working on some of stories. The way that hauntings can animate alternate lives, shadow lives, paths taken and not taken.

Looking at the popularity of writers like Carmen Maria Machado, for example, people today seem very drawn towards the ghost story. Why do you think that is?

One reason why writers keep coming back to the ghost story is that, like the fairy tale, it is endlessly flexible. It can be reimagined and recontextualized again and again, which is why I think the form has such incredible endurance. Contemporarily, we’re at a moment where, for white America, the unwillingness to look, listen, learn, study, and engage, is having disastrous consequences. Historical truths and realities and how they shape the present are being denied. In that sense, I think that that this is a perfect time for the ghost story. As I was saying before, the form is very adept at looking at what the characters don’t want to look at.

What about actual physical ghosts? Have you ever seen one?

I don’t know if seen is the best word for this.

Or, experienced?

I've always had a healthy respect for the supernatural. I lived with my grandmother when I was a teenager, and she 100 percent believes in ghosts. One of the first things that she said when I moved in with her was, there’s a ghost in the house from long ago, if you see her come down to the kitchen in the middle of night and turn on the water, don’t worry. I never saw the ghost and just chalked it up to my grandmother being eccentric. So, the idea of supernatural happenings wasn't necessarily foreign to me, but it was not something that I had experienced.

And then when I was working on my first novel around 2013, I spent a summer at a residency in the Florida Keys that was horribly, terribly haunted. The manifestation wasn't visual, it was more auditory, and I wasn’t the only person that was affected, several of the other residents were as well. We heard doors shaking, cabinets opening and closing, crying and screaming outside when there wasn’t anyone outside. We would wake up in the middle of the night and all our chargers and lamps would be unplugged. We would plug them back in, and the next time we woke up they would be unplugged again. We had an exorcism ceremony through the residency because the affected people were absolutely losing their shit, as you can imagine. The exorcism fixed the problem because we were unaffected for the rest of the residency.

What did the exorcism consist of?

It’s a little hazy because at that point I had not slept in maybe 10 days, and this is July in the Key West so it was 102 degrees outside. The whole experience was fairly hallucinatory. In my memory we had agreed on something to communicate to the ghost, a ritualized saying that we would repeat again and again. There was a lot of lighting of candles in different places and making requests of the spirit while they were burning. We lined all the doors and windowpanes with salt. It was some sort of special salt that the exorcist brought with him—but maybe it was just sea salt, who knows. I felt sort of ridiculous when I was doing this but then we didn't hear a peep for the weeks that followed.

That’s all so scary.

It was terrifying. I have a healthy respect for the supernatural, but I want it to stay in its lane and I’ll stay in mine. It was genuinely very frightening and not something I would necessarily be keen to experience again.

I have one other story, which is a little less sensational. After my father died about a year and a half ago, I arrived in Florida and was staying at my sister's house and one of her dogs, Champ, slept with me. I had a dream that my dad was speaking to me through Champ. I woke up at dawn and this dog, who usually sleeps like a log, was sitting upright beside me. And his mouth was opening and closing, and it looked as though he was talking. We just stared at each other like that for a little while, and then he laid back down.

There can be such a desire to try and figure out what it was. Was it a supernatural thing? Was it grief? Was it exhaustion? But I think I’ve given up on trying to explain moments like that, and just allow them to the inexplicable things that they are. That's precisely the kind of moment that I'm drawn to writing into fiction, these experiences that can't be explained. Toni Morrison has this beautiful quote from an NPR interview she did, where she says, “If you’re really alert, you can see the life that exists beyond the life that is on top.”

There’s so much in that beyond that’s deeply mysterious to me, but I believe that it's there, and that it matters. I’m interested in allowing the presence of the beyond in and thinking about what it has the capacity to communicate to us that cannot be conveyed through more corporeal channels. These questions were of deep interest to me when I was working on this book.

Do you think it might be dangerous in a way, to remain open to the beyond like that?

Dangerous how?

Emotionally, psychologically, spiritually.

I think one's relationship to whatever dimensions that exist or don't exist outside of corporeal life is deeply personal. For me, I do think writing fiction requires a degree of emotional or psychological risk. If I'm not risking something, I feel like the story isn’t risking anything. And I do think stories need to be willing to take risks. This can manifest in all kinds of ways. I always want to be very thoughtful about the risks that I'm taking in fiction and not just risking for the sake of risk. That’s what boxing is for [laughs].

A lot of the stories in Wolf did take risks. “Hill of Hell” was an emotionally difficult story to write, and there was emotional risk there for me. I also hope that the spirit of that risk is felt and present in the story. A lot of it is waiting for the right time to write something. “Last Night” was the most autobiographical story in the collection. It's a story that I had tried to write many different ways and many different times. When I wrote the draft that’s in the collection, it was the first time that I tried really writing in an autofiction kind of style. But I was also just ready to write that particular story. Some of it was technical barriers, but it was also emotional readiness. I wasn't prepared to be that raw and vulnerable with that material. I had to wait for the moment when I did feel like I could go there. Questions of risk are questions of timing as well.

When you're speaking of unknown terrains, I'm reminded of how your characters frequently find themselves as tourists in foreign countries. Why is this a setting you find yourself circling back to?

I think that there are specific ways shifts in location can disorient the gaze. There’s a part of my experience with that exorcism that’s glazed into my memory more than anything else. If you can imagine the residency was set up like a compound that took up about half a city block. There were six of us there, and half of us were affected, which is to say we experienced the haunting, and the other half did not. I asked the exorcist, why did these people get off so easy? Why was it just us? And he said, with absolute authority, “you have the wedge.” His theory of hauntedness is that every place is haunted, there are ghosts all around us at any time. Inside each of us is a wedge, and some ghosts can fit into the wedge and others can’t. Which explains why five people could go into a quote unquote haunted house, and maybe only two would say they felt a chill.

I think that travel, and the very particular ways in which it can dislocate and disorient the self, can create new wedges that new types of things can get inside. I was really interested in that in the titular story, and the way that the protagonist taking on her sister’s identity causes her own sense of self and her own life to go completely haywire. I think that travel, because we are removed from our usual context, allows for things to happen that would not have happened at home. That can be very good for fiction. I was thinking about this with “Karolina”: on what terms could these two women meet each other again? They could have encountered each other at home, but there is a kind of charge and intimacy and privacy that can happen between these two women because they're in a hotel room. Because there is this temporariness. Everything is intensified, everything is heightened.

Speaking more broadly about form, I was really influenced as a younger writer by abroad novels. I still really love great travel literature, and at the same time I think the history of the of the abroad novel is riddled with problems. Whiteness that’s unexamined, imperialistic urges and so on. It’s up to readers whether this project is successful or not, but one thing that I've been alert to is trying to find new shapes and imagine new possibilities for travel literature.

Is this desire to place characters in alienating positions why they all seem so disconnected from each other? It seems very difficult for your characters to find any authentic social connections.

They’re all very solitary, and for many of them we’re meeting at times where their lives have been horribly fractured by loss or secrecy. This has given way to a deeper alienation to those around them. A lot of these characters are in the liminal space after a really formative loss. The kind of loss where you walk into the moment one person, and walk out a different kind of person; and maybe you don't know what that means exactly, you just know that something somewhere inside you has fundamentally changed forever.

Maybe these characters have walked out the other side of that door, but they don't yet know what that changed self means for them. When you're in that state of profound limbo, it's hard to make connections with the people around you. I was really interested in writing into these metamorphic, mysterious emotional landscapes.

I wanted to circle back to something you were saying at the beginning of our conversation about America's rejection of history. This seems juxtaposed with the fact that for your characters memory is something that's always present on an endless loop.

These characters have pasts that are really bearing down hard on them, and because of that, memory is very activated. The word looped does feel apt. There's a whirlpool effect, and they're circling and circling and trying to not get sucked down into the center.

But this individual memory is very different than national memory, than having a collective understanding of our true history as a country. There's a lot of people who are receptive to trying to figure out how to meet this moment, but still don’t understand how we got here. The answers are all there, it's all encoded in our history: a history that has been undealt with, unconfronted, and unrectified, in any kind of public institutional way as well as in the context of people's private lives.

That was something I thought about in “Lizards,” where on the one hand what the husband is doing to his wife is really horrifying and unforgivable. But on the other, she is a character who is enraged by Kavanaugh's presence as a likely Supreme Court Justice yet is all too eager to blank out at the end of the day and to avoid the harder questions. What is she as an individual willing to change in her life? What is she willing to give up? What is she willing to do differently to prevent another Kavanaugh from being in such an immense position of power? The answer to that question is probably not that much. She’s a character whose relationship between her own life choices and the larger power structures that she's kind of starting to notice is really, truly unexamined.

“Karolina” is uncanny in its prediction of how mainstream liberal feminism would treat Tara Reade. There’s a criticism in there of a selective politics, where there’s no real application of politics to one’s own life outside of a specific agenda.

“Lizards” and “Karolina” are the two stories where that relationship was the most on my mind. The narrator in “Karolina,” for instance, would consider herself to be a feminist and a Democrat. She would be completely horrified by Kavanaugh and Trump. And yet the patriarchal violence in her own family, in terms of her relationship with her brother, has gone completely unexamined and unconfronted. Moreover, she has been complicit in the abuse of her sister-in-law. That’s something that so many people are wrestling with in their own families. The application can’t just be external: protesting, donating, making calls, writing emails. That work is vitally important, and we all need to do it. But the application must be internal as well. That comes down to the power dynamics within our own family structures.

This character was never physically violent, but she helped to cultivate an environment where violence against her sister-in-law was possible or even permissible. I was thinking about personal relationships to power and how what goes unexamined can have consequences in powerful and terrible ways as we move through our lives in the greater world.