Timo, a logician at the University of Iowa, the campus and surrounding “speck of a city” in which Brandon Taylor’s third book and second novel, The Late Americans (Riverhead), is set, is idly perusing the boyfriend of a friend’s sexually explicit uploads to a popular content subscription service when he suffers an access of sadness, as unexpected as it is gradated and subtle:

“The more Timo watched the clip, the sadder it made him, and when he began to watch the other clips that sadness became something else, more complicated, as if the watching were a sieve through which his emotion was being passed over and over again, and in the refining, more of its distinct character emerged.”

The boyfriend and subject of the video is Ivan, an ex-dancer turned finance grad, and Timo’s friend is Goran. While Goran, a music student, comes from wealth, the Black adopted child of affluent white parents, Ivan “lives on student loans, amassing a pile of debt in order to study the meteorology of money,” and has turned to pornography as an additional means of income. Ivan and Goran’s relationship is languishing. They fuck other people, but no longer each other.

Timo’s grief is rooted in the fact that he has recently broken up with Fyodor, a utility truck–driving local who “worked in beef, as a leaner.” Fyodor’s job consists in cutting away “the pinkish fat and connective tissue from the dark red flesh, which was rather soft and delicate, like dough or cloth,” that passes in industrial quantities along the plant assembly line. Both Fyodor and Timo are of mixed-race parentage; otherwise the couple are nothing alike. Timo comes from a secure middle-class background. Fyodor grew up in poverty, irretrievably estranged from a father who rejected him and his mother to begin a second family. Timo, brilliant, cultured and sensitive, never misses an opportunity to remind the laconic but earnest Fyodor how much he loathes his job, right up until Fyodor, patience worn to a nub, resignedly throws Timo out.

These are just a few of the characters that inhabit The Late Americans. Over the course of the novel the reader will also meet Seamus, an impassioned and truculent MFA student in poetry, the dancers Fatima and Noah, and a closeted local older man, the violent, unpredictable and enigmatic Bert. While some characters are friends, or lovers, or both, many are only obliquely aware of each other. The Late Americans follows the events, major, minor and mostly somewhere in between, that occur in their variously intertwined lives over the course of several months.

It is a multi-perspective novel, told via the points of view of multiple characters, but while usually in such a novel the perspectives will tend to recur—the viewpoints rotating regularly between a core cast—The Late Americans advances through a kind of chapter-by-chapter relay. With a single exception, the point-of-view characters get to be point-of-view characters only once; once their chapter ends, the baton of perspectivity is passed on to another character.

The momentum of the novel, as it proceeds, is less linear than modular, recombinant. Instead of the usual effect of a novel, where events largely succeed each other in a temporal line moving in a single direction, the storylines in The Late Americans seem to branch and slide about and lock into a constantly renewing and increasingly complexly faceted shape, before reconfiguring again with the addition of the next chapter.

Even as the novel manoeuvres toward a close, where another novelist might narrow in on their most “important” characters in order to neatly tie up arcs and plotlines, Taylor continues to foreground the perspectives of hitherto “peripheral” characters. But no one, of course, is peripheral in their own lives. Which is perhaps the point.

The narrative innovation of The Late Americans pays off thanks to Taylor’s assured, precisely textured prose. Each chapter brings us expertly into the skin of a given character. With rich economy, Taylor sketches exactly the amount of backstory we need, transmitting how and what each character notices—and fails to notice—of the world about them. The prevailing emotional logic of their current circumstances is made completely legible, even when that logic is at its most inchoate or elusive or jaggedly paradoxical.

Here, as in Real Life and Filthy Animals, Taylor’s (mostly) young millennial characters, so often feeling worn out and burned up the way only the young can, languish in the grooves of inured habit, probing at the memories of their bitterly self-destructive behaviours, the way one compulsively tongues a sore tooth. Fearing themselves incapable of mustering the generosity and patience true intimacy requires, they torment the lovers they believe will soon see through them. And yet when the moment they most dread comes to pass, and things finally come apart, they become generous and almost masochistically docile with each other. They love and care for each other and become bored and vindictive together. They push each other away, and grow doleful and innocent again in the agony of their solitude. Then they come back together again, irresistibly.

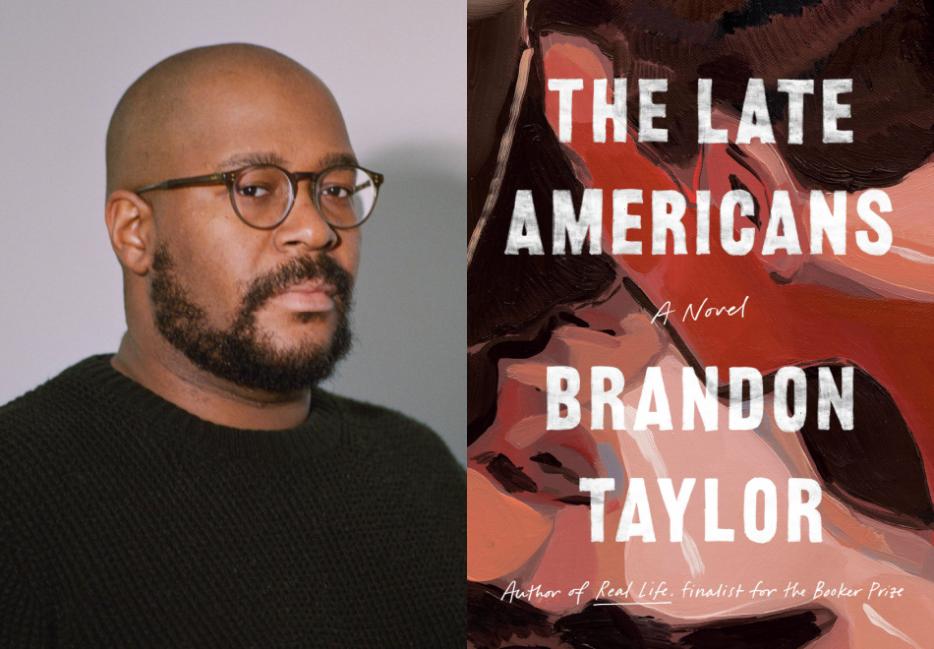

The Late Americans is a compelling, clever, funny, structurally audacious book of relentless psychological acuity, emotional resonance and technical control, and reconfirms Brandon Taylor as one of the preeminent American authors of his generation. In person, and via Zoom, Taylor is warm, deprecating, eloquent company. We spoke a few weeks preceding the book’s publication. What follows is an edited transcript of that interview.

~

Colin Barrett: The Late Americans is a very fun book. It takes a lot of structural innovations, even risks. You have a big cast of characters, and the way they are presented and interrelate—it’s very complex. Was it fun to write the book this way?

Brandon Taylor: The drafting phase was a lot of fun. It didn’t feel complicated while I was drafting, because I was just following the relationships. It’s like when you first join a large friend group, and you slowly get absorbed into it—you’re enjoying learning about the relationships as you go.

[When] I finished the first draft and took a step back I was like, Oh no, how do I arrange this in such a way that it makes sense and feels like a novel, that time is passing and that it isn’t just a bunch of disconnected episodes in this group’s life? The vision and trying to justify to myself writing about creatives—that part of it was much less fun and it ruined my life for a long time. At one point I just stopped writing and took up film photography for a year just because, yeah, absolutely not. I survived. I love the drafting phase. That’s where all the fun is because you’re not responsible for your mistakes until much later.

Did you just go straight through in the drafting or rework stuff as you went along?

I never rework as I go. I think the first draft was begun in January of 2019, and I finished it somewhere in the summer of 2019. The first draft was done very quickly. The honeymoon phase was over very fast. But in my memory, it feels like I was in this great world, just finding these people and having fun. By the time I finished it, it was the longest I’d ever worked on a first draft of anything. My friend Garth [Greenwell] was very quick to tell me that writing a book in six months is actually still very fast. But then there was the revision. The revision, and the shaping of the book, getting it right, that took, you know, three to four years. And that was arduous! I was changing things, like, two weeks out from sending the book to print even. It was a long, long, winding road.

The book opens in the middle of a writing workshop at the University of Iowa. We meet our first point-of-view character, a frustrated, prickly poet named Seamus. A fellow student’s poem is being critiqued, but in short order the critique devolves into a bitter exchange of increasingly personal grievances, with Seamus at the centre of these exchanges. The chapter is intense and cutting and messy, the hothouse emotional temperature expertly invoked. And maybe we think we know what kind of novel The Late Americans is going to be, what shape it might assume. But within a few pages we are out of the classroom, out of the academy. The chapter continues with Seamus travelling across town to a local hospice, where he works as a kitchen porter. In the next chapter we meet Fyodor. He’s in a relationship with Timo, also a grad student, but Fyodor himself is a townie, employed in a local meat processing facility. While most of the characters are grad students of one kind or another, not all are. So, all through the novel there is this movement, this constant tacking back and forth between the rarefied environs of the academy and what Seamus—even as he himself is out in it, chopping vegetables for minimum wage in an institutional kitchen— refers to as “the real world.”

The contours of Seamus’s own life are a complication of the very distinction he draws, and constantly throughout the novel there is a resistance to settling into easy categorizations and neat definitions. Things are never just one thing. Was this porousness, this spilling over of boundaries, always part of the conception of the book, or did it emerge during the writing of it?

In my first two books, I was exploring the idea of what a campus is and what it means. In Real Life there is almost a naive sense of what a campus is and how it functions, how there are grad students and then real people. The book very much turns on that binary and that dichotomy, but it’s mostly interested in the lives of the graduate students. I feel like with this book, I wanted to write a more truthful articulation of what that’s like, what happens when a working-class person goes to graduate school and gets to be in this rarefied space of the quote unquote campus, but also has to work a job, because his stipend isn’t enough to support himself, which is the reality of many MFA and graduate students. I wanted to write about what it feels like to occupy different rungs in these parallel hierarchies.

I wanted to approach the idea of a campus in a much less naive sense. I think that a college town is first and foremost a town that has a college campus in it. There are these boundaries, but they are so fungible, and permeable, and they produce all these weird moments of irony and tension when a person who isn’t supposed to be on one side of that boundary trespasses to the other. I remember in college the writers would be having, like, a house party, and then right down the street, the undergrads were also having a house party. There was never any sort of spillover, except sometimes on the way home, when everybody would end up walking in the same direction. You would get this temporary mixing of the groups, and yet everybody had their own distinct little cohort to return to. I found that really interesting.

I was trying to represent the way that even though these characters belong to their circumstances, their contexts, there’s always spillover and confluence. Things are always running through each other. I liked using that as a site of drama.

That comes through in your handling of perspective in the book, the way characters are centred. Each chapter is seen from a particular character, but with the exception of Seamus, they are only point-of-view characters once. While the characters do continue to show up in each other’s chapters, we only get something like “inner access” for, say, Fyodor or Ivan or Fatima, once. Then others, like Bert, never get a point-of-view chapter. How did you select your point-of-view characters? And was the “rule of one” part of that early, generative first draft stage? Was it always inbuilt to the novel?

I did have an unofficial rule that I wanted [each chapter] to be, like, one thing, one person. Seamus only had one chapter originally, but I was really struggling with the book and I realized that, oh, Seamus needed a job. In the original version, after the seminar he goes home and writes a poem.

In realizing that he needed a job, I had to split his chapter. So now he goes to the hospice, to work. Then the poem writing, which occurs in his second chapter, becomes a sort of refrain in a way. I thought splitting Seamus’s chapters into two did something to tighten up the book. It creates these two phases: there’s the opening phase, which begins with Seamus, and the second phase, the closing run of the book, that begins again with Seamus.

I found having these two Seamus chapters very structurally useful. With every other character, initially I was in the mindset that they would have an episode and then a character who had appeared in that chapter would take over the narration. As I went along I didn’t want that to get too obvious. For instance, Fyodor’s chapter heavily features his boyfriend Timo. But instead of following Fyodor’s chapter with a Timo one, we go to Ivan instead. Then there’re characters like Goran, Ivan’s boyfriend, who doesn’t get his own chapter, even though you’re sort of expecting it. Instead, you get to build this idea of Goran from the different people who see him and interact with him.

I was just following my instincts, choosing what would seem dramatically interesting, what would seem more fun to write. Later on, the book spools out toward these other characters, like Noah and Daw. I did want to avoid having the book cohere too tightly around a particular set of characters. So if I had written a Goran episode, for example, that would have tempted me to then go back to Timo, and it would have locked down the shape of the book too prematurely.

I wanted to preserve a sense of randomness, because that’s how friend groups often are. Like, who becomes the locus of the friend group drama does shift constantly around, and I wanted to preserve that aspect. I wanted to impart the sense that you are not sure where the story is going to go next, because that is life, and that is how it feels when you’re sort of falling in love with a group of friends; you don’t know who’s going to do the random thing that day that causes everyone to end up in chaos!

Seamus is exasperated—and in turn exasperates—his fellow poets, whom he views largely as identity grifters of sorts. He believes they seek to insulate their writing from meaningful criticism by tangling it up overtly with their own identities; they foreground, or affect to foreground, the personal and the autobiographical in their work, in a way that, as he sees it, sabotages evaluation because to attack their work is to therefore attack them. Which Seamus nonetheless does, because it’s pretty clear much of his professed aesthetic reservations about their work are actually personal, or have become so. Seamus wants to believe that art can transcend the personal, can escape the contingent moment and so on, even though he himself so often doesn’t.

That opening chapter is a ferocious depiction of the workshop as this whirling centrifuge of personal antagonisms and egos and shifting alliances, out of which the occasional piece of art is flung like shrapnel, and Seamus both rages against and compulsively participates in this dynamic.

We talked earlier about how there’s no clean line between, say, the campus and the town, the town and the campus continually contextualize each other. There is the same sense here about art, how it too always has a context, is embedded in the material conditions and contingent moment in which it is produced. Was that something you wanted to deliberately foreground?

In some ways it was the impetus of the book. I was in an MFA program from 2017 to 2019, during a very particular moment in American culture, where it felt like we were collectively rending our garments and trying to move ourselves into becoming martyrs in some sort of identitarian theology. It was very strange. I was so frustrated by what felt like a total failure to engage our thinking in what—to me and my very pretentious MFA brain—seemed a meaningful way [with the moment we found ourselves in]. I found myself looking around and often feeling very cranky and very annoyed. And I was like, I’m going to write about this, I’m going to write a little MFA takedown piece! Initially, the book started as a parody, as a satire. But very quickly, I realized, oh, I can’t actually write like that. I need to take this character seriously. I found that I really did care about this person, Seamus. The drama here isn’t that there’s these objectively true or false ideas about art. It’s that Seamus is a person who feels like he’s staked his life on art and that his classmates haven’t. They are deigning to judge him when he feels like they aren’t even having the same kind of conversation.

I wanted to write characters who had feelings and ideas about art. At the end of my first semester in grad school I sold my first two books, and so I found myself still in grad school while also editing books for publication. I felt myself becoming a commodity. Suddenly I had all these feelings about art and commerce and the marketplace of ideas. It was a very strange place to find myself emotionally, and I wanted to be able to write about it.

In my first two books, I was able to write characters’ interiority, but the only things they were able to have interiority about was, like, themselves. They couldn’t have interiority about art. I didn’t know how to do that. Then I read Garth Greenwell’s great short story, The Frog King, which unlocked the ability in my brain to be able to write characters who could think about and feel art. It unlocked a way for me to write characters thinking about art and fiction. That was the other impetus for this book—wanting to write people who had feelings about art, and to be able to turn over those ideas, like, what makes a piece of art worthy? What makes a person a good artist? Where does audience come in? Where does market come in? Where do all these cheap discourses about art that we have in society come in? And what happens when those discourses start to erode one’s sense of individuality?

So, yes, it started with me being very annoyed about many of the things that annoy Seamus in that opening chapter. Then, of course, it spools out and takes on a life of its own, and all these other people come in.

One thing that felt important to me was to write about different experiences of art that weren’t just within the context of an MFA workshop. That people who, like Fyodor, work in meatpacking plants of course experience beauty all the time. They can experience beauty; they can have an aesthetic experience. We think about these things as being class gated, but they are not. My grandfather was an illiterate farmer, literally an illiterate farmer. Sometimes we’d be working in the fields, and he’d look up and see a cardinal flying across the field and say, Take a look at that. Isn’t that beautiful? That felt important to me, to write about art not just from the context of grad school, but from life. From the whole of life.

There is something wonderfully paradoxical in the cumulative effect of the book. Each chapter so deftly captures a sense of the character it focuses on, pulling us right into their lives, but then the chapter ends and we are dropped into the middle of another character’s life. And so the book is full of intimacy, but it is a controlled, and curtailed, intimacy. The characters are pulled close, then they are restored to a relative distance. Can you speak a little on that, on what you were hoping to achieve with this chapter-by-chapter movement?

My first book, Real Life, inhabited one consciousness over a period of several days. It contained one perspective. Even my second book, a collection of short stories, is at its core a suite of stories about, like, three people, and really it is also primarily about one dude, one consciousness, followed over several days.

Writing this book, I was just hungry to write different perspectives. Different voices and different ideas. I feel like I wanted it all—I was so monstrously greedy in this book! So part of the book’s shape comes from wanting a sense of sprawl. If I could write a novel like Anna Karenina—I would love to be able to do that.

When I think about what I’m good at, I feel like I’ve got a grasp of atmosphere and mood and tone. I feel like I’m good at interior psychology. But trying to stretch that over six hundred pages is impossible. It’s just not going to work. How should I deal with that? How can I create, like, a Tolstoyian sprawl with my sort of Ibsenian impulses? My solution was: we’ll just be with each person for an episode, and then we’ll switch, and the choreography of the novel will emerge from that, that handing off to another person. I’ll let the characters come in and come out, and you’ll get direct and indirect doses of them.

I wanted it to be like a piece of choreography. It’s not that you’ll need a flow chart to map out exactly who is where and who is with who. In the end, what I wanted was to communicate a sense of these people’s lives, that they were here and that they loved each other, that they fought and they burned each other, literally and psychically, and that they lived.

There’s a passage that I particularly love from the book that concludes with “…as if the watching were a sieve through which his emotion was being passed over and over again, and in the refining, more of its distinct character emerged.”

To me, this is what is so magical and memorable about The Late Americans. It’s almost as if you are taking these very general and universal feelings—inadequacy, neediness, loneliness, disconnection, generosity, yearning—and passing them through the sieves of all these different characters. And the gamble you’re taking is that instead of diluting those emotions, it is precisely that repetition, that recurring procedure, that’s going to allow, as you write, “more of the distinct character of those feelings to emerge.”

Maybe that’s reductive or highfalutin or something, but it seems that what you are after is the bringing alive of the vividness of these emotions, in all the variety and particularity with which they endlessly emerge in our lives, and it is precisely by drawing the story through this series of dispersed perspectives that you achieve that?

I think about what D.H. Lawrence said, which is that the novel is the greatest invention mankind has discovered for the depiction of the subtle interrelatedness of things. You take these quite abstract notions, and just through the rhythms of character and plot and scene and setting, you get something really beautiful and vivid. I think the way that we meet the characters again, and again, in these different ways, in different registers, in different moments, does create a sense—not necessarily that as you leave the book you know exactly what Goran’s personality is, for example—but you have some sense of the resonance of his particular human circumstances. Of what a person like that, in a place like this, would feel should X or Y happen.

When you realize someone’s positionality in the world—I find those moments really moving and really profound. When I think about what I remember from Tolstoy, it’s that. That a person, a person here, at this time, felt this—that’s amazing to me. That we can use the novel to do that as creatures.