Fifteen years ago, Carol Off met a man in Afghanistan. His name was Asad Aryubwal and he agreed to give her an interview that would expose the atrocities committed by warlord Abdul Rashid Dostum. For a reporter establishing herself at the CBC, it was an opportunity. The documentary that included the interview, In the Company of Warlords, went on to win a Gemini Award.

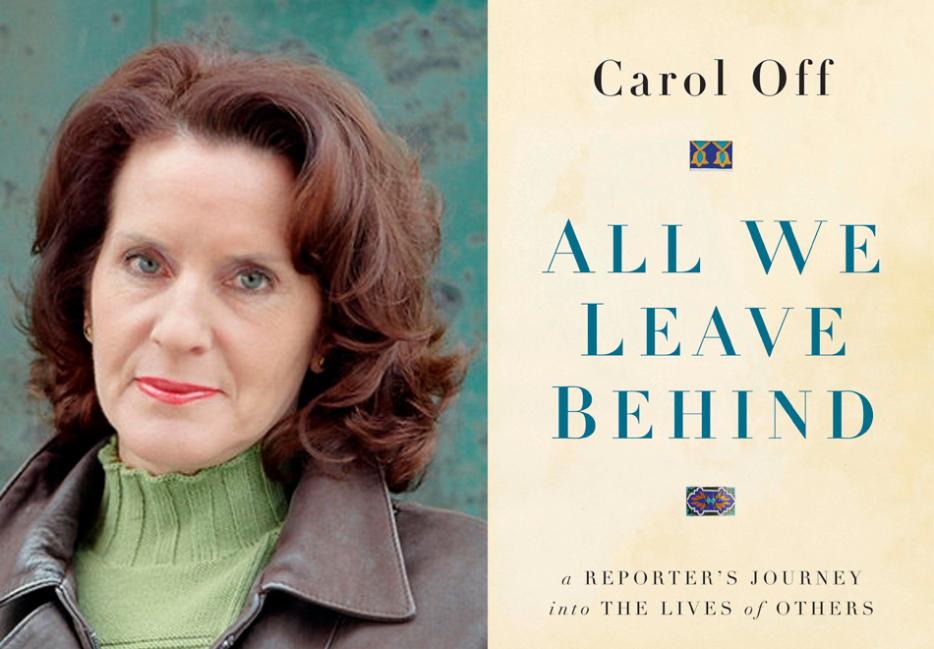

When Off returned to Afghanistan four years later, she filmed a second interview with Aryubwal. Soon after, the general’s men paid him a visit and told him to leave the country or die. In her latest book, All We Leave Behind (Random House Canada), Off details how she discovered that her journalism had threatened the lives of a father, mother, and five children. Her involvement with the family—first as a journalist and then as a friend—sparks a nine-year-long process in which she places her humanity over her journalistic obligations and tries desperately to help Asad and his family find refuge in Canada. What follows is a harrowing account of a family scrambling for their lives across three countries and of a corrupt and needlessly bureaucratic refugee screening system. It’s an experience that forces Off—the longtime host of acclaimed CBC radio show As It Happens—to confront what it means when the right choice as a journalist isn't the right choice as a person.

Katherine Laidlaw: When did you think this story could become a book?

Carol Off: The first time I knew I wanted to write a book was actually a moment when I was really angry. I got a phone call from the family to say that they had been at the UNHCR [the United Nations Refugee Agency] trying again to get their application through for refugee status. They had been approached by somebody who said, "you’re going about this all wrong. This legitimate thing you’re doing is not the way you do it. The way you do it is you wire money to Moscow, $50,000 USD for your family, and we will send a message inside the UNHCR and your paperwork will be completed." He refused to do it. And I was so angry about that criminal element that I thought, I’m going to write a book.

When you first started your career, you sold all your belongings and went to Pakistan with the promise that CBC would maybe buy one of your stories if you could secure a difficult interview. Why did you do that?

Because I had no money otherwise. And I needed to do something. I was stuck. I didn’t have a career. I was told, you’ll never cover conflict, you’ll never cover war. You’re a woman, you can’t do that. I went to some outlets and said, I’d like to go and do this—I’ve proven that I can do this in Pakistan. I covered a hijacking, I covered the war, I’ve covered all these things. And they said, no, you can’t, we have a policy, we don’t send women. Some said, a woman would be a liability, she would endanger everybody else in the crew if you send a woman in. In 1987.

Why did you go anyway?

I wanted to feel the heat of being a journalist. I wanted intensity.

Have you had other sources over your career stick with you the way the Aryubwals did?

There is no story I have done that I was as touched by as this one. Asad, the father who gave me the interview, was an interesting man. I’d interviewed people like him before. But it was his family, particularly his oldest daughter Ruby, who really drew me into their orbit. I kept in touch with her. I justified it in my head—it was still journalism, she was telling me what was going on in Afghanistan, I was learning and keeping in touch with the story. And so it seemed like she was just a contact. But when I realized how much peril Asad was in, that he’d fled for his life, for his family, that he was living in exile, I knew I had to help.

You sent the family money over the years, which they used in part to put their children through school. Did you have a conversation with yourself about the ethics of doing that?

Never. I didn’t care what I would lose or sacrifice in the way of journalistic policy if I helped him, because it was just the right thing to do as a human being. I thought being a human and a journalist were the same thing. I went into journalism with a moral compass and a sense of what was good and fair. And I thought I had my humanity intact in my career. Suddenly, I’m faced with my journalism and my humanity not being the same thing. When the chips were down, I decided to go with the humanity.

Through the book, you contend with feelings of responsibility and guilt over endangering the lives of the Aryubwals. But Asad agreed to the second interview, despite knowing there would be potential consequences. Does that relieve you of some of those feelings?

If I had known he was in danger, I wouldn’t have done it. People give these interviews and tell us these stories because they think it will make a difference. They want to expose the injustice in their country because they’re hoping that exposure will change things. They take enormous risks. Trying to figure out how to protect people without actually helping the bad guys by deciding, no, I don’t care if you want to tell me your story. I’m not going to do it because I’m not going to put you at risk. Then you have actually done what the tyrants want, which is self-censorship. So you’ve got to think, how do I let you tell me, which I need you to do, while at the same time not endangering you. I think my sense of where that balance is has changed.

As journalists, how can we protect people?

Just check back with them. In other interviews, I’ve many times travelled doing stories where I get back to my hotel room and I’m sure someone’s been through my things, they’ve been through my notes, they’ve been through my tapes. I’ve arrived at the door of somebody in another country and they say, you can’t come in, the police have just been here. How did they know I was coming? I’ve interviewed young people who are idealistic—they’re in Cairo, in Tahrir Square, the Umbrella Revolution, and they’re willing to tell you that they want democracy and liberty for the country. They’re caught up in the moment. It’s not just that you do your due diligence beforehand to make sure you’re not putting people at risk, but that you look back over your shoulder and call back and stay connected and make sure that they’re okay.

Now, having seen what the refugee system is like, and struggling on this end to try and help a family reach safety, what do you think should change?

It was so frustrating. I would think, what am I doing wrong? There are millions of refugees in the world and they’re all on the move. Why can’t I make progress here? Why can’t I help them? These walls, these obstacles, this corruption. I thought, if it’s this difficult for me in Canada with a lot of connections and resources, if I can’t do it, what’s it like for them?

It’s extremely difficult to get into this country. Anyone saying, we can’t be a doormat to the world, you can’t just let people in here willy-nilly—believe me, they’re not letting people in here willy-nilly. The amount of screening is absurd. When you make it that difficult, people will find any way they can. Because their lives are at risk. People will do anything. We would do anything to get out of the mess these people are in. We would scale walls, we would climb through fields, we would walk across Europe, we’d get into rubber dinghies that were unsafe and maybe lose our children. If we make it so difficult for people to find refuge and shelter, then they will do anything they can to get here.