Our existences are a testament to the people before us. Our traditions and rituals, the flavours that become familiar on our palate and celebrations we engage in have origins in atrocity, resilience, conquest, redemption and resistance, but are mostly rooted in how we’ve developed our means of survival and how we’ve preserved self and community. But what happens when we move to new homes or become displaced? When geography ruptures our proximity to ways of living and knowing, it can often act as a catalyst of discomfort, as we wrestle with feelings of shame and reckon our own sense of authenticity and connection to our culture.

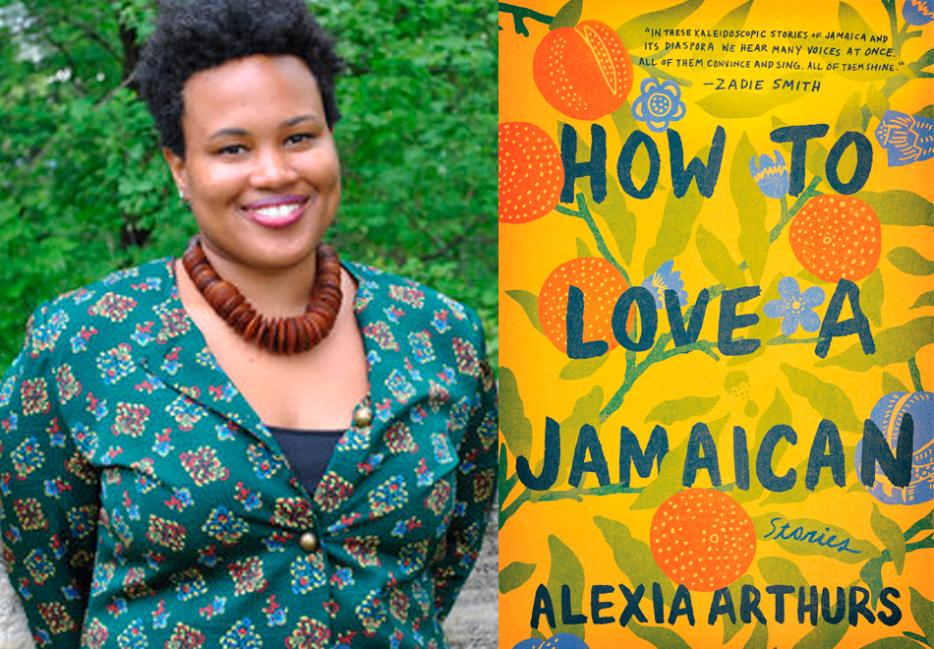

Alexia Arthurs’s anthology of short stories, How to Love a Jamaican (Ballantine Books), is host to these nuances. Her characters negotiate who they were, are and aspire to be as they confront and traverse their problems with proverbs and parables of their nation’s past. Arthurs creates a world that reminds us that though we have the ability to engender entirely different realities than the ones that we are currently acquainted with, distance does little to sever ties to the places, people and practices of a life now foregone, especially when love is involved. She breathes life into common experiences of immigrants, refugees and people who leave their homeland for unfamiliar grounds. But using Jamaica as a backdrop offers a unique perspective into what makes Jamaicans’—diaspora included—collective realities so distinct.

To live in Jamaica is to exist in a paradox. A story, typically passed down orally, speaks to the island as a place, during the era of the transatlantic slave trade, where the most unruly and resistant slaves were sent to be “seasoned,” or broken down, into slavery. Centuries later, that same badniss is an element of our collective identity that we shoulder with pride. It’s evident in our music, our fashion, our language and our dancing but is juxtaposed by the remnants of a religious, colonial past that creeps its way into contemporary institutions and widely held beliefs. The land of wood and water is duly known for having the most churches per square mile in the world, and the influence of Christian values permeate nearly every aspect of our lives, both overtly and insidiously. What this means for many is a limitation of one’s actions and a silencing of desires for fear of reprisal, or being sequestered into the fringes of their communities.

Whether it be alleviating or even amplifying parental pressures, having the space to explore sexuality or stepping out of the confines of tradition, for many Jamaicans on the island and in its far-reaching diaspora, the idea of living in the Global North—though accompanied with its own particular challenges—offers a chance for rebirth or at the very least an opportunity to step into a different kind of truth in a foreign utopia, sans the anticipation of judgements that lurk in the shadows of our subconscious.

How to Love a Jamaican amplifies a perpetual wrestling between the old world we knew and the new world we know, and how one navigates life’s obstacles with, without or in spite of love.

Sharine Taylor: Often, love is explored in the book through the lens of a woman, or how we—island born, part of the diaspora, expats—experience love from the closest women in our lives. What is it about Jamaican woman and how they know love that makes it such a central theme?

Alexia Arthurs: I was interested in exploring how Jamaican homes are often female-centric, which is to say that much of the caring, nurturing, and home-making is women’s work. I’ve experienced love from Jamaican women in a fierce, stubborn way. It’s a love that’s protective and consuming, sometimes frustratingly so. Perhaps the determination and intensity of this love is because so much is shouldered by Jamaican women.

There seemed to be this juxtaposition between two worlds: Jamaica and America or farrin, really, that represent the old world as a place of possibilities in theory, and the new world as a place of possibilities in practice.

I was at a party recently when I asked a woman what part of Guatemala she was visiting from. “Guatemala City, obviously,” she said. “Obviously?” I asked. People have such an interesting relationship with this question of regional possibility. We are taught to rise to a position of value within the limitations of our geographic situation, but that a place like the United States is at the top of the hierarchy of possibility. And yet for many people, the American dream is a myth. I think about this a lot. My family had been middle class in Jamaica, and when we moved to New York when I was twelve, I looked around at the other children in my school and at the homes of my relatives who had been in the States for years already, and had the feeling that my family was starting from scratch.

Many of the characters reconcile their present-day issues with nuggets of knowledge from their past, even if they don’t wholly agree with them. What is to be said about how we navigate through obtaining our desires or standing in our truth and whether or not those truths and desires conflict with lessons that have been ingrained in us?

I believe that we are always in conversation with our past—the things that have happened to us, the learning we have consciously or unconsciously done. As rooted as we are in the future, the body, the soul, and the mind remembers. It’s healing work to navigate old stories in the midst of new ones, to ultimately have the life that we want.

There are moments when the traditionally understood characteristics of what defines a Jamaican man and a Jamaican woman are disrupted—like in “We Eat Our Daughters,” “On Shelf” and the chapter that holds the title of the book—especially when confronted with living in between new borders. What is the larger commentary of how our ideas of masculinity and femininity change between or beyond borders?

I mean to suggest that if our ideas about gender roles are flexible based on the cultural context of where we are, doesn’t that point to the fact that gender roles are a construct? Wouldn’t that suggest that they aren’t real?

That’s true. A lot of what I witnessed my mom doing in my childhood, especially as a single parent, defied what would be considered traditionally feminine and sort of echoes a colonial Caribbean era that rendered both men and women as being physically capable of doing the same kind of labour.

Yeah, I think back to my childhood, a time when my mother used to make coconut milk from scratch on Sundays for the rice and peas. If I’m remembering correctly, she would crack coconuts open, grate the meat and soak it in water to make coconut milk. So-called feminine work. But she also built a chicken coop when my father took too long to do it. I remember he was surprised to come home and see that she had done it herself. I’m always amazed by the duality of the roles Caribbean women take on, sometimes forcibly and sometimes because it’s the only way to get things done.

I would say that there’s a responsibility or burden one assumes, unwillingly or unknowingly, when they have their eyes set on leaving for seemingly “greater things.” We know this by the luxury surrounding possessing a visa, or the pride that parents have when their children are studying abroad and the pressure that’s associated with what we know to be success. How are you in conversation with those ideas?

I’ve experienced that commonly held narratives of pursuing greater things abroad don’t tell the full story. It’s more complicated than the grass being greener. Lots of immigrants struggle for a long time, and others never stop struggling. Many foreigners are homesick and lonely, and are navigating the pressures of succeeding from back home. It doesn’t help that in a country like the United States, foreigners are made to feel unwelcome. I want to tell truer, more nuanced stories of what it’s like to leave home.

And sometimes those stories don’t have happy endings.

Yes, this is true. It’s heartbreaking to think about.

The characters often teeter between who they are and who they are supposed to be, given what their upbringing has led them to believe. Do you think that there exists a middle ground between the two?

I don’t know that there is a middle ground. Perhaps it depends on the individual. Or perhaps there are different kinds of middle grounds. Maybe a middle ground only needs to be observing the old stories, and then choosing to act in an honest, intuitive way. I only know for sure that I’m interested in the internal struggle of expectation versus reality, especially in a small place like Jamaica where communal pressure can be pressing. I think about this in my own life. I was raised to be a good Christian traditional Jamaican woman, first in Jamaica and then in a close-knit Caribbean community in New York, and now none of these roles are interesting to me. Yet, I was telling a friend recently that I’m still unlearning ideas I gained a long time ago about myself and the kind of life I should want.

I found that in most cases, when the characters drew on their most familiar banks of knowledge, it helped keep them grounded. Would you agree with that?

Oftentimes, I feel drowned by the writing process, so I’m unable to make conclusions about characters, to see them with a critical, objective gaze. But I see what you mean. Does that feel relevant to your own life? I’m thinking this makes sense for me personally, that intuition and groundedness is impacted by everything I know to be true and real and meaningful.

It does. Sometimes I’ll hear my grandma’s voice reciting some proverb like, “Wa sweet nanny goat ago run him belly” (What’s good for you now may not be good for you later), and I wrestle between that and what I want. Sometimes it’s helpful but I do wonder if it’s this imaginary paranoia that’s rooted elsewhere. Without trying to sound morbid, I found that death as it’s used multiple times throughout the novel likens the newness of unfamiliar places? It’s unknown, scary and can be seen as a means of escape but in actuality it’s just another state of being that has its own set of rules and regulations to navigate. What would you say to that?

How funny, your question is making me realize how much death is in the collection. I love that the imagination can put language and imagery to what is unknown and shrouded in mystery, like the nature of death. Also, I find that death can be a pressure cooker for character development.

Speaking of characters, we are first introduced to mermaids by way of a quote from Jamaican-born author and professor Kei Miller and are later introduced to them in various different points in the book. What perspective do mermaids lend to the telling of these stories?

A friend, more woo-woo than me, once told me that perhaps mermaids left our restraining world for another plane of existence. I love this. She and I had been discussing mermaids as inspired by my story “Slack,” in which two little girls in Jamaica are sent mermaid dolls from the States. I think of mermaids in the collection as an evolving metaphor. In one story they speak to the desires and dangers of what lures us, in another story they speak to transgressive sex which is a part of the mythical of mermaids, and so on. In a larger sense, mermaids are being used throughout the collection to challenge the mythology of contemporary Caribbean life.

“Shirley From A Small Place” felt like all of the lessons from your stories culminating into one. It’s sort of this colliding of old and new—ways of knowing, ways of living, our truths and realities—and how our identities shift to reflect that. What is to be gained from Shirley’s narrative?

I love that you feel this way about Shirley’s story. When my agent and I were talking about ordering the collection, we both had the sense that “Shirley from a Small Place” read like it should close the collection. Perhaps for the very reasons you’ve brought up. At its essence I wanted to write a story about a girl who had been everywhere and had seen everything worth seeing, and yet the small place she came from could hold the healing power of home.

Right, it’s sort of like, no matter what happens, no matter how transgressive this place could feel at times, it’s still the only place where you’d want to be?

Absolutely, speaking for myself, I am first and foremost Jamaican. So much of who I am is because of where I was born and raised and the people who I call my family.