The author of Mother of God discusses the limitations of realism, Frank Bidart, and the anguished duality of shame.

Standing in the wreckage of these spaces unlocks a sensation people often crave, but can’t name.

It’s an imagined past, a pastoral imaginary, an alternate timeline in the multiverse.

Latest

The author of Mother of God discusses the limitations of realism, Frank Bidart, and the anguished duality of shame.

Standing in the wreckage of these spaces unlocks a sensation people often crave, but can’t name.

It’s an imagined past, a pastoral imaginary, an alternate timeline in the multiverse.

“Bird,” he cried, “I come on behalf of the emperor. Your voice is all anyone speaks of.”

She stops to look into her mother's face. It is smooth and blank as a stone. Nothing emerges; nothing shifts.

Who could possibly fall asleep to the sound of Fran Drescher’s voice?

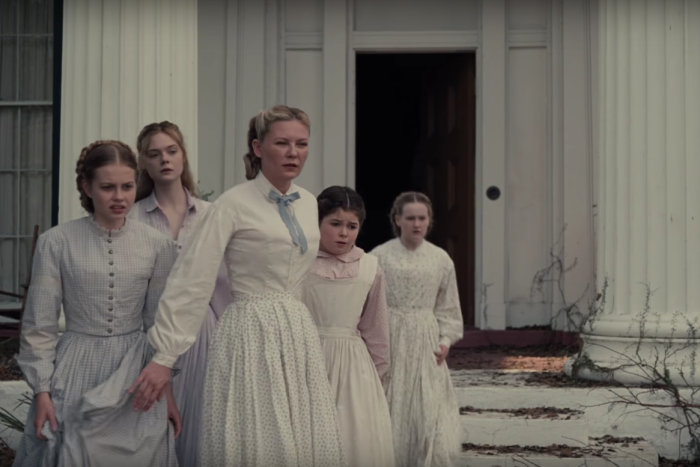

Like so many of her heroines, the director seduces to control.

Why did I go to work for the TSA? To try to connect with my father? To soothe various concerns as a new father myself? Was I researching a book? Having a midlife crisis? All of the above?

My father defaulted on his dreams, abandoned his daughter, and resigned himself to living on a futon in his parents' living room. Then he bought a two-foot-tall stuffed rabbit.

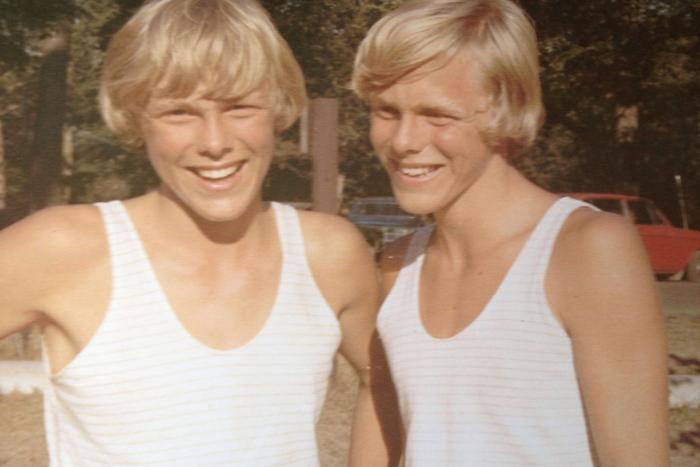

The fact that I’ve always had an exact replica of my father, with a startlingly similar voice, mannerisms and, well, face, never really struck me as exceptional until he passed away.

The author of Fugue States on upending Diaspora clichés, disingenuous narrative arcs, and dharma.