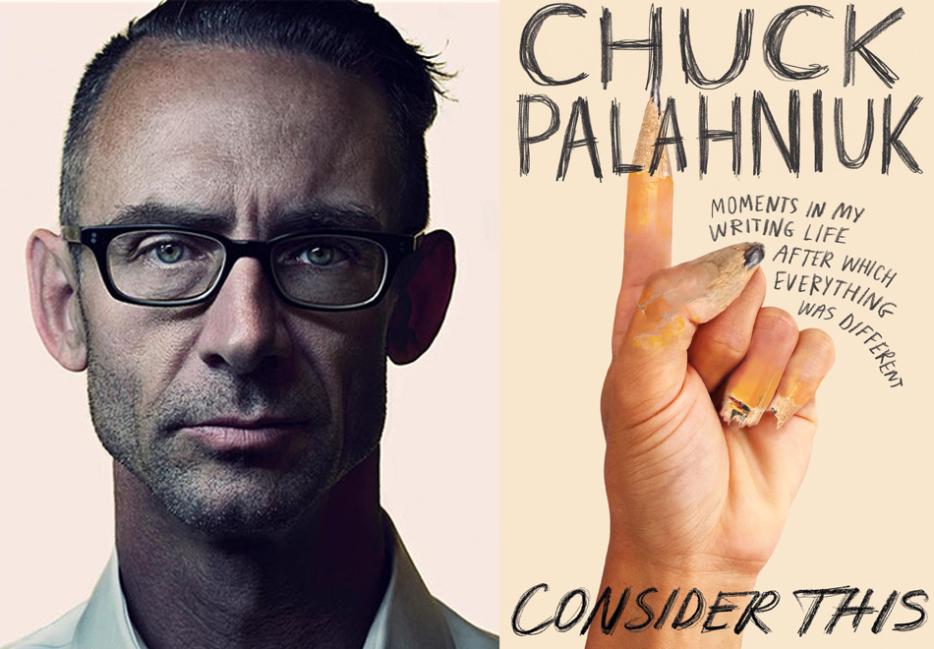

There’s a short but telling section in Consider This (Grand Central Publishing), Chuck Palahniuk’s new memoir on writing, that simply says: forget about being likable. The book, a collection of personal essays on everything he has learned about writing in the last twenty-five years, quotes people from Tom Spanbauer to Amy Hempel to Ursula K. Le Guin on technique, style, and form. It was Spanbauer, a former student of Gordon Lish and the author of five novels himself, who created the Dangerous Writing workshop, which pushed Palahniuk to write Invisible Monsters and then Fight Club in the mid-’90s. What Spanbauer meant by “dangerous writing” was to explore the work that personally scares or embarrasses the author; to make it dangerous is to express those fears honestly through art. It was through Palahniuk I found Spanbauer’s workshop, too. In 2013, I spent a weekend in Portland working on a short story in that Dangerous Writing workshop, and then two subsequent years working with Spanbauer on my own novel.

Palahniuk has never been one to write characters people would see as likable or upstanding; rather, they are deeply flawed. In Choke, one of my favorite books by Palahniuk, the narrator, Victor, concocts a convoluted plan to pay for his dying mother’s hospital bills which involves pretending to choke on food at restaurants. While he chokes, he waits for a person to “save" him so they can bask in the glory of being the hero, and as a result, these "saviors" send Victor money, which he uses to pay the bills. In Diary, the main character, Misty Wilmot, suffers through caring for a husband in a coma following a suicide attempt, after having given up her dreams of an art career to raise a family; she struggles with her past of poverty, the desire for fame, and the oppression of the wealthy islanders who are related to her comatose husband. Many of Palahniuk’s characters are trying to find success through some kind of glory, and are willing to humiliate themselves, lose all dignity, and hopefully live through it to get there. In Consider This, Palahniuk says this kind of obliteration of self is also the writer’s job, that the point of writing is to coach one’s self where one would never have gone voluntarily.

The problem with being vulnerable as a writer is there’s a paradoxical desire for the work to be liked, whether that means validation through the publishing process or being accepted by some sort of readership, while simultaneously shutting out self-critique or worry about whether others will accept the work. I once talked to a writer friend who discussed the need to “lean in to your disaster”—disaster being the raw, distinguished pain of one’s words which makes a writer’s work unique, wild, and telling. Often in Spanbauer’s workshop, this practice started with an assignment about the thing you’re most afraid to tell. The idea was you might exhaust all of the emotional or psychic pain of a moment through writing, make the pain totally vulnerable, and come to a new place on the other side, changed.

Perhaps this is what draws people to Palahniuk’s work: the sense that a flawed character always has the hope of being redeemed (even if they never are). I recently spoke with Palahniuk by email about craft, writing workshops, and who inspires him to be a better writer.

Elle Nash: Could you talk a little about the effect of Tom Spanbauer’s teaching on your life? Consider This is dedicated to him, and the subtitle of the book is: moments in my writing life after which everything was different, a callback to his workshop. His influence on me has been very deep, and it is hard to say what guidelines I tried to follow before his workshop, even. I loved reading your words about him in the book. I know you’ve discussed his workshop a lot, mostly I’m curious to know what your ideas about writing were before Tom—before you were changed?

Chuck Palahniuk: Like so many would-be writers, prior to Tom I was a Lousy Stephen King Copy. Or I was a Pathetic F. Scott Fitzgerald Copy. Meaning I'd read and try to emulate the style of successful writers. Among the first things Tom told me was, "The world already has a Stephen King." And then he showed me empirical ways to unpack and reverse engineer storytelling, and in doing so create my own style and voice. Instead of mimicking the superficial aspects of a famous writer, under Tom's direction I could begin to build the deep framework needed for truly unique stories.

Presuming there is no workshop to give feedback, how do you think a writer can learn to trust their intuition?

Minus any workshop, go to parties and tell your stories. Test to see whether people engage with them and give an emotional response. Also test to see if strangers approach you with similar stories from their lives, ones you might use to expand your original story. Parties are the best. A distant second-place option would be "open mic" public readings. Such readings allow you to hear where a story earns an emotional response, but most of your audience is too competitive and distracted (drunk) to offer anything beyond their laughter or gasps or groans. This sort of testing will help build your story-telling instincts.

On the note of workshops, I’ve always felt that art is never a solitary act. I’d love to discuss with you the effects collaboration can have on a writer’s work—from trusting their peers in workshop to simply feeling inspired by another writer. Who inspires you to be a better writer?

Go to where the rawest stories occur. In Alcoholics Anonymous I'm always blown away by the most unlikely people inventing a phrase or sharing an anecdote so tragic that it makes the listeners laugh. My background is in journalism so my impulse is always to preserve, archive, curate these incredible moments. Good, real people telling true stories inspire me to become a better writer in order to better honor such stories.

You said once your formative years were the punk years. What makes something punk versus not punk? Is there contemporary fiction you’d consider punk these days?

My reference was to an observation made by Billy Idol. He said that all punk songs started abruptly, ran three minutes and fell off a cliff at the end. Hearing that I realized that my best short stories began at full throttle, went only a few pages, and ended—blam. With that insight I could start to vary my pace and length in fiction. But in my reading I still prefer work that drops a reader instantly into a reality and resolves circumstances in twelve pages rather than twenty or forty.

Are there any short stories or authors you recommend that drop the reader into reality like that?

For instant immersion, I look for short stories. Mark Richard's The Ice at the Bottom of the World, The Collected Stories of Amy Hempel, Honored Guest by Joy Williams, The Informers by Bret Ellis, Miles from Nowhere by Nami Mun, and Jesus' Son by Denis Johnson.