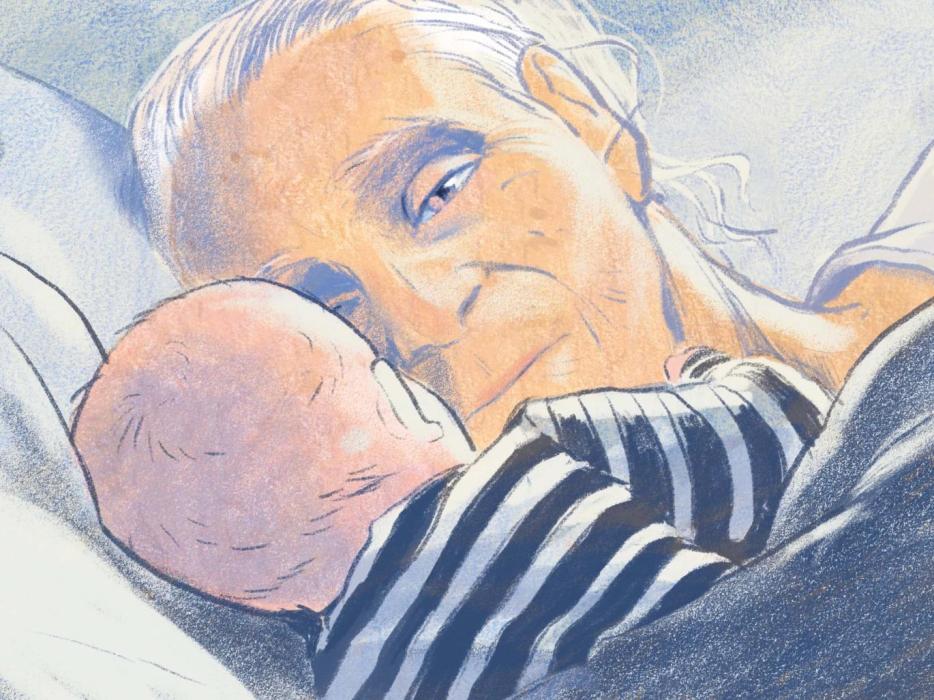

Our grandmother and the baby sat in bed together. The bed was in the dining room, and the light was bright. It was late July in Southern California, the hottest summer on record. Ripples from the backyard pool reflected on the ceiling. The nurse said that babies emerge from the womb crying because they feel a sense of vertigo.

It was my cousin’s baby, and he was eight months old. Our grandmother was eighty-eight. The two, it seemed, understood each other better than anyone else in the house—and there were lots of us, four grandchildren and two great-grandchildren and two daughters and one son-in-law. The baby was just a visitor. He’d come from a place that none of us could remember. Our grandmother was headed there.

I spent a lot of the summer watching grandma and the baby stare at each other. They stared for long, unbroken stretches, communicating on a private register. I liked to think that the baby was giving grandma advice, or telling her what she might encounter, stars or shadows or flashes of light. When they touched, a mysterious energy pulsed through the room. Then the baby would cry, my cousin would gather him, and we’d resume the day’s activities—reading to grandma, spooning her thickened water or pureed peaches, placing a mask on her mouth and pumping steroids into her lungs.

*

It took me four hours to drive from Las Vegas, where I lived, to my hometown, where my grandmother lived. The first time I drove that summer, it was nighttime. The headlights of the long-haul trucks illuminated Joshua trees and darting bats. A friend had offered to come with me, and we kept each other awake with a carton of cold brew, store-bought strudels covered in powdered sugar, and auto-tuned music we’d heard at middle school dances. I considered the call I’d received from my mother a few hours earlier, when she told me about the fluid in my grandmother’s lungs. Grandma had been in the hospital a week; doctors thought she’d had a stroke, but this was something else. Mom’s tone was different than when she’d told me of my grandmother’s other hospital admissions in recent years. This time, I detected fear.

When we pulled up to the ICU at 1 a.m., my friend stayed in the car. Inside, I found a hospital room tableau: my grandmother, asleep, draped in IVs; my mother dozing on a chair next to her. In the afternoon, when I returned, my grandmother was awake. “I’m alive,” she croaked, self-deprecation edging into her voice. “How hot is it where you are?”

She was an unusual grandmother. Every day when I was growing up, she drank a senior Diet Coke from a drive-thru and drove my siblings and I to school in a dented Toyota Tacoma. She liked turquoise and sterling silver; she hated police. She taught my brother to read. She owned at least three microwaves. We shared a bedroom for a while, twin beds with matching quilts. Marry a doctor, she’d tell me. Someone with money. But after thinking about it, she’d usually revise her advice to: Find someone good to you. She told my cousin: Find someone you can bear to look at over coffee every morning.

When I looked at her now, she struggled to eat, lest food get into her lungs. This was called aspiration. There were also problems with her potassium levels (hypokalemia), oxygen levels (hypoxia), and fluid in her lungs (pulmonary edema). Her face drooped. Her appetite waned. She slept for long stretches.

I’d recently trained as a death doula to learn how to shepherd the dying through their final weeks. The point of the work was to decentre the medical system and its attempts to defy death and instead treat dying as a normal part of human existence. I was also curious about what it was like to die. Was there, in this life, a way to get close to the experience? To witness the threshold without crossing it?

*

Death, wrote the Irish poet John O’Donohue, is “there at your birth with you.” The moment we are born, the adage goes, we begin to die. But if you could put a pin in the moment my grandmother’s dying quickened, it would be three years earlier, with the first ER visit. Mom had driven over to grandma’s house, knocked on the door, no answer. When she let herself in, she found grandma unresponsive on the couch. At the hospital, doctors said she’d had a major stroke. She woke up, saw my mom, and asked, “Is that a new blouse?”

At the stroke recovery centre, grandma had a room that looked out to a field of buckwheat. Mom pointed to a pepper tree swaying in the wind. “Coyotes probably live under there.”

“Is there a house under there?” grandma asked.

“A coyote house,” I said.

She couldn’t remember her age. Fifty-eight? she asked. Eight-five, we corrected. Numbers were difficult, and dates. But she knew the name of the president (Biden), her daughters (Kelly and Kathy), and herself (Betty). Specialists came in the mornings to teach her how to walk, holding her by the waist as she shuffled forward. She had once taught children how to read; now the specialists taught her how to write.

One night, mom went to the kitchen to get grandma’s dinner, and alone together, grandma and I dipped into the well of her memory. Despite her general confusion, the past stuck.

She remembered Tucumcari, New Mexico, the dusty town on Route 66 where she grew up. There was nothing much to do there but drive up and down Main Street, or climb to the water tower and look out over town. She remembered a single phrase in Spanish, from her time teaching elementary school in Albuquerque: Este es mi gato. Mi gato bebe leche. She remembered driving south to another town and dialling her parents from the motel bed, confessing that, at age seventeen, and still in high school, she’d eloped with my grandfather. Twenty years later, he left her for another woman.

She once told to mom that she was afraid of dying alone. But she seemed to relish her lack of romantic attachment. She never again wanted to merge her life with another person’s.

I suspected that, at this point, she knew her world would change. That, after forty years of living alone, she could no longer live without the intrusion of other lives. That night in the stroke centre, mom helped her change into a red night gown. I pulled off her socks. She sat back, lay down flat, grabbed the bed’s rails, and pulled herself up to the pillow. She couldn’t get into bed the usual way.

*

Three years after the stroke, grandma left the hospital through home hospice. The paramedics brought her to my parents’ house on the night of a full moon. They strapped her to a stretcher and wheeled her down the steep driveway. There were no streetlights or house lights, and the moon wasn’t yet sufficient, so we lit their path with our cell phones and car headlights, and she looked sheepish being carried down the driveway she’d driven thousands of times. The caseworker arrived with a clipboard full of questions. Has she lost weight over the past few months? Has she fallen? How many hospital visits? Incontinence? Method of eating? Has her appetite declined? The questions were about her, not for her. We went over medications, blood thinners, and steroids.

Dying, we learned, requires a lot of paperwork. The advance directive can state whether or not the dying person wants resuscitation or a feeding tube. Hospice nurses measure temperature and blood pressure. Caseworkers document the condition of the home. The family members make arrangements with a funeral parlour. They pick out urns and purchase plots of land at cemeteries. They order engravings on headstones.

My brother ordered a camera from Amazon. It was the kind used to monitor babies and pets, but in our case, we would watch grandma. We watched her when we were far away, at work or running errands or back in the places where we lived—Virginia and Northern California and Colorado and Nevada. We watched her looking out the window, at the pool and at the trees, and we watched as one of us painted her nails, or read her a book, or told her a story, or rubbed her feet, or put ChapStick on her lips. We watched her sleep. We watched her stir in the night. We watched mom rush to her bed. We called it the gramcam.

*

The days took on a shimmering, liquid quality, each one seeping into the next. Grandma liked watching the baby crawl across the floor, searching for blocks, putting things in his mouth. He liked chewing magazines. Sometimes, his three-year-old sister would prance barefoot over the cool tile and hug him. Grandma liked to watch her, too. She’d watch her follow the trails of ants outside over the patio, or jump into the pool.

Grandma liked sitting outside with the sun on her face, and listening to screech owls at night. She liked when a praying mantis landed in her hair, and when my brother flew his drone overhead. She liked to hear about the world outside my parents’ house. My sister told her friend gossip and roommate drama; I told her about the meteor shower I watched in Nevada.

On a balmy afternoon, as we talked about weeds in the yard—grandma loved to nitpick over yards—mom said, “You’re beautiful.” Grandma frowned. “Repeat after me,” mom said. “I am beautiful.” Grandma shook her head. She was tired of talking about herself. In her pre-dining-room life, she’d always been stubborn, and if she didn’t like the way a conversation was heading, she’d cut it short. But mom wanted to hear her speak. “Remember,” she said, “how the divorce lawyer asked you out?” Mom prompted her with another memory: After the divorce from my grandfather, grandma went on one date, and to her horror her date tried to kiss her. No more dates. For the rest of her life, she fended off potential suitors.

I’d never heard the divorce lawyer story before. There was so much about her life I didn’t know.

When the baby cried and my cousin was talking to grandma, my siblings and I would try to console him. He was heavier than I expected, and I held him away from me, as I would a snake. He moved his mouth toward my chest. Mom eyed him. “You aren’t getting anything from those,” she said flatly. She was disappointed she was not yet a grandmother; one night, when I was pretending to sleep on the couch, I heard her ask grandma if I’d ever get married.

In bed together, baby and grandma resumed their staring. He made lips like a fish and grandma mirrored him. He gargled. What was the baby telling her?

“He asked, ‘How are you doing?’” grandma told us. “And I said, ‘I’m fine.’”

*

One evening, my sister and I came with questions from friends. We were searching for ways to pass the time, to entertain grandma. We’d never deliberately looked to her for wisdom, and asking a dying person to offer advice for the living felt like a trope. Yet we asked her to play the part, and grandma received us at her bedside like an oracle. Her trembling throat reminded me of the flesh underneath a chicken’s beak.

“What’s the best decision you’ve ever made?” one friend asked me to ask grandma.

“Getting my master’s,” grandma said. Her voice was hoarse.

“What’s the most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen?” asked another.

“The mountains of New Mexico,” she said.

“Should I be open to a past relationship that is my greatest love, but also my greatest heartbreak?”

“Walk away,” grandma said.

“What’s the most important thing in choosing someone to marry?”

“They give more than they take,” grandma said.

“Is dating math or magic? A numbers game or a spark?”

“Spark,” she said.

“Should I get back in touch with an ex?”

“If he was good for you, he’d come around,” she said.

“What’s your biggest regret?”

“My marriage,” she said.

“Should I buy a house with my boyfriend?”

“Walk away,” she said.

Our questions were the kind you might ask a Magic 8 Ball while hoping for a certain answer. Shake the ball, close your eyes, squint as the letters become clear—yes? We were young, in our twenties and thirties, and wanted yes to romance. But grandma’s single love story had hardened her. In its place came self-reliance, a different kind of mythology. Yet as her body wore out, I saw that myth breaking down, too. When she grew tired of the questions, my brother spooned her water, for her throat.

*

According to my death doula handbook, two weeks to a month before death might look something like this:

Sleeps or drifts much of the day

Eats very little or may stop altogether

Drinks less

Difficulty swallowing

Episodes of apnea (arrested breathing pattern)

Disoriented and confused

Visions of people who died previously

May speak about dying

Swelling in the extremities may increase

Wounds won’t heal.

*

The drive from Vegas became familiar, routine, even. I’d pass a giant plaster ice cream cone, an abandoned water park, a faded yellow RON PAUL REVOLUTION sign, Zzyzx Road. Cresting a mountain pass, I’d drop into the suburban sprawl of Southern California’s Inland Empire, where the smog sometimes mingled with wildfire smoke and stained the sky orange. My sister drove with me once, the week a tractor-trailer carrying lithium-ion batteries exploded, shutting down the interstate and stranding thousands of travellers without food, water, or gas in 110-degree heat. We missed the accident by days.

I thought of these trips as part of a pilgrimage, a journey to the in-between. My parents’ house was tilting into the supernatural. Grandma was starting to see lights no one else could see, and she would glance upward from time to time, as though peering into her future. She spoke about wanting to go home.

One night, grandma saw her former students. (She’d taught second grade for decades.) Mom, hearing her rustling on the gramcam, emerged from her bedroom to find grandma staring into the kitchen. “The boys,” she said, “need to take their tests.”

“What tests?” mom asked.

“The English tests,” grandma said. She pointed to the kitchen, angry.

“How many boys are there?” mom asked.

“Fifteen,” grandma said. Mom shuddered at the thought. She mimed holding on to a stack of papers, and passed out their tests.

During the day, grandma saw visions of the bird and garden decor shop she’d opened with my mom fifteen years prior—the reason she moved to California from Virginia after she retired from teaching. The shop had been the centre of her life. She’d oriented herself around accumulating items—wrought iron flowers and plastic flamingos and ceramic fountains and metal birdcages—and spent her days sitting behind the counter, gossiping with other shopkeepers on her street.

From her bed, grandma saw strangers in the shop. They were clearly hostile, because she tensed. I approached the group of invisible people in the kitchen, trying to see what she saw. Were they emissaries from the afterlife, trying to tell her something? Or would they reveal how she was feeling? I wondered if she was afraid of dying. She’d told the hospice chaplain that she worried she wouldn’t make it to heaven. She feared that she hadn’t been good enough in this life. She worried she wouldn’t see her daughters again.

“You’re trespassing,” I told the people in her shop. “You have to leave.

“They left,” I told her, but she shook her head. Dad tried a different way, putting on a show of marching them to the front door.

She had benevolent visitors, too. She saw her parents, long gone. She saw her grandson, my cousin, who had died just before she had her stroke. “He isn’t dead,” she told my aunt, his mother. “He’s right here.”

One night at my parents’, when I was sleeping on the couch, I heard grandma tell mom she had to leave the dining room, go to the assisted living facility where she used to live. Her voice was faint; it took an exacting effort to produce words. “I don’t want you to have memories,” she said.

*

On a morning in August, grandma demanded I take her for a drive. Her visage had changed. It was cold and bitter, and she wouldn’t make eye contact. Indeed, her whole demeanour had shifted, as though she had been overtaken by an entirely different person. This happened more frequently now, though it was hard to predict when this cold grandma would emerge. Once, she receded into this persona when her bedside table was too messy; another time, when mom told her she couldn’t go back to her old house. With faltering strength, she would turn her body away and refuse to speak. We thought it had to do with her sense of losing autonomy and the ability to communicate. That’s why babies cry, a hospice nurse had told us. They can’t tell us what they need.

Her arms had become twigs, and it seemed like we could fold her up. How could we even get her into the car? In a fit of fury, she grabbed the bed rail and tried to stand up on her own. We conceded. What else to do but try to make her happy?

Dad scooped her up and placed her into my parents’ Prius. I pressed the child lock. She stared out the passenger window, fuming, and an eerie quiet descended into the car. In the 1960s, after interviewing hundreds of terminally ill patients, Swiss psychologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross theorized that there were five emotional stages to dying: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. (In the popular imagination, these are called stages of grief, and thought to be linear; Kübler-Ross originally intended the stages to describe the dying process, and clarified these emotional responses can be cyclical and repetitive.) “Few people place themselves in the patient’s position and wonder where this anger might come from,” she wrote. “Maybe we too would be angry if all our life activities were interrupted so prematurely.” If we were told when to lie down, when to be still, when to eat and drink, when to sleep. What we can and can’t do, like go for a drive.

When I got to the stop sign at the end of our road, I asked grandma where we were going. She jabbed her finger left without looking at me. I drove to another stop sign. Another jab left. Then right. At the stoplight, left. We’d left the neighbourhood and were on a main road. “Where are we going, grandma?” I asked. Still, she did not speak.

We passed the Carl’s Junior where she used to stop for her senior Diet Coke and my order of biscuits and gravy on our way to school in the mornings. Were we headed to my high school? When we were teenagers, grandma would turn sour if my siblings and I ran late. She’d give us a lecture if we didn’t bring our clothes down for ironing, if we forgot our lunches, if we weren’t dressed modestly. Was she inhabiting those moments, fifteen years earlier?

We didn’t have time to drive all the way to the campus. At a stoplight, I made a U-turn. She grabbed the door handle. “I’m sorry, grandma,” I said. She was silent.

She’s agitated, the hospice nurse told mom. Terminal agitation—a possible symptom of impending death, according to my doula handbook. A restlessness, an itchiness, a discomfort. We could give her painkillers to make her feel better. “She won’t let go,” the nurse said.

“But I don’t want to let her go,” mom told me, weeping on the couch.

The next morning, grandma pointed to a fraying cookbook. “Quiche,” she said. Mom made it every Christmas, and if we blended it and gave her small spoonfuls, she could eat it.

As I mixed the eggs and cheese together, I felt a pull at the back of my shirt. When I turned around, no one was there. I looked at my back in the mirror. Nothing.

*

Mom asked the hospice nurses if grandma was “transitioning,” the word they used for active dying. It was difficult to gauge timing. Some days she was alert and joking; others she was sleeping and silent, curled deep into herself. Her fingertips were turning purple. Her breath was becoming more ragged. The hospice nurse warned us this would happen: that she would start breathing with her mouth, with gasps and long pauses between inhalations. Her blood pressure might decrease. But the nurses told mom not to focus on the vitals or numbers. We could guess, but never predict, precisely when a person would die.

It’s generally understood that when a person is dying, the body slows down. But recent research has found that in the moments before death, the brain becomes hyperactive, potentially producing some of the behaviours we were seeing in grandma. In the early 2000s, Jimo Borjigin, a physiologist and neuroscientist at the University of Michigan who studied circadian rhythms, and in particular, melatonin secretion in animals,, made a curious discovery. After two of her test rats died during an unrelated experiment, she found they’d been awash in serotonin—twenty times the animal’s normal amount. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter best known for making us feel happy. “These animals,” she thought, “must be hallucinating.”

I spoke with Borjigin months after I witnessed my grandmother’s decline. I wanted to know what I had been seeing, and why. Dying is shrouded in spiritual mystery, and rightly so—there’s so much we can’t understand, and won’t understand, until the moment we die ourselves. Even then, perhaps we will never understand. But surely the body has its reasons for giving us visions and showing us white lights, signs we often interpret as the afterlife encroaching into our life on earth.

Bjorgin agreed. For another study, she collaborated with University of Michigan physicians to examine hospital EEG data used to detect seizures in cardiac arrest patients. She found four patients who had died while being monitored. After they’d been taken off their ventilators and cut off from their oxygen supply, two demonstrated increases in high-frequency gamma waves, which indicate cognitive activity. The activity occurred in a part of the brain associated with altered states of consciousness, suggesting the patients might have seen visions or light, even though their eyes were closed.

Scientists did not exactly embrace her findings, she told me, because her work upends the long-held scientific idea that the dying brain is inert. It complicates the notion that there is a firm line between life and death. Even more controversial is its potential affront to religion; the near-death and dying experiences we’ve often attributed to gods and angels may instead simply be chemically mediated.

But I’ve come to think that science and mystery aren’t at odds. I wasn’t sure about my grandmother’s malevolent visions—they are messages I will long try to decode—but the gentler ones, the serotonin and gamma rays, the light and sound and sights, seemed to be the body’s way of dissolving our terror of the unknown, of blunting physical pain, of giving peace. The body eases our passage as we leave it.

*

We began to sense that she wouldn’t die in our presence. That she was holding on until we were gone. So we turned off the gramcam and booked our plane tickets. I planned a drive north, to the mountains, where the air would be thin and I would think only of breathing. The hospice nurse told us that we shouldn’t administer her oxygen anymore because it would stimulate her heart. She no longer needed her heart.

On one of our last days, the chaplain had us pray around her bed. We formed a circle, mom and aunt holding grandma, cousin holding baby, three-year-old peering through her legs, brother off early from work, dad taking his lunch to be with us, sister on video call. Four generations of family in one room and beamed across timezones. We touched grandma’s feet and hands and hair. It’s okay to leave when you’re ready, the chaplain said.

Grandma was wearing her glasses, hand pressed to her cheek, as though settling in to read before bed. Where was she? I couldn’t tell. After the chaplain left, she turned to me, her face questioning. “How old was I when I died?” I told her what we both knew. Eighty-eight.