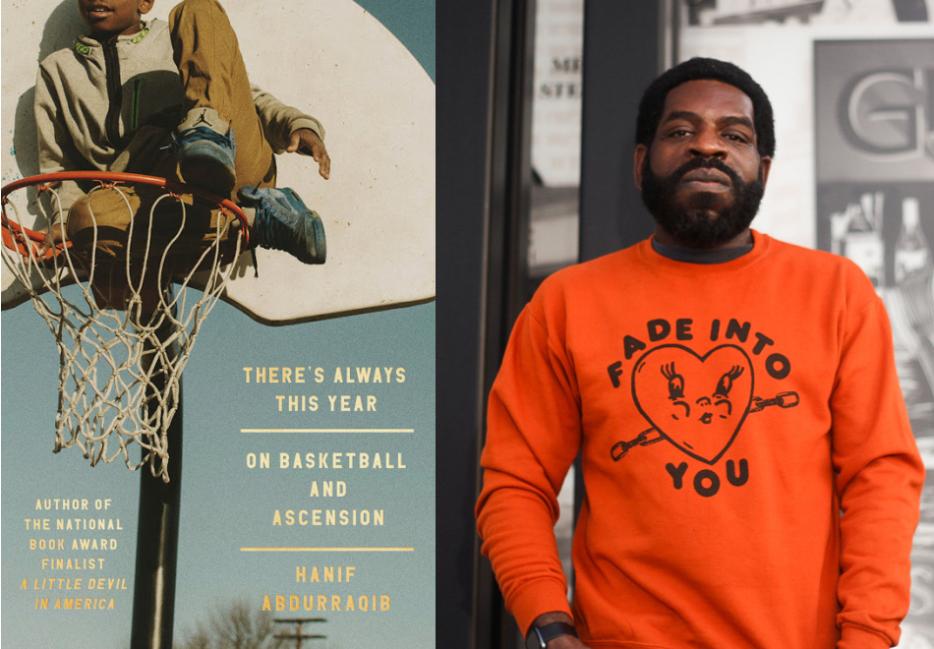

There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension (Random House) is the culmination of six years of dreaming for poet and essayist Hanif Abdurraqib. The book has followed him in draft form through a MacArthur Fellowship, the releases of three other award-winning titles, the hosting of two podcasts, creating over a hundred Spotify playlists, and through the paradigm shift that the pandemic brought to the world’s doorstep. All of this momentum culminated in a sense of catharsis as Abdurraqib approached the book’s release date during our conversation in late March.

Though the book is ostensibly about basketball, There’s Always This Year is also fundamentally shaped by Abdurraqib’s keen eye toward social, political, and cultural dynamics, imbued with poetic pacing, musical allusions, and a vibrant mental map of his hometown. Through this pathway, There’s Always This Year shows the ways in which our lives are marked by the people we love, the losses we endure, and the departures and returns that define our existence. “A good court,” he writes, “is not defined by infrastructure but by who shows up to play on it.” The conviction at the core of this story is that the deliberate channelling of devotion—be it toward other people, ideologies, or the divine—drives individuals to the arenas of their choosing, moulding both their communities and their personal identities.

There’s Always This Year charts where that sense of allegiance leads the basketball community, Cleveland, and Abdurraqib himself. In it, we follow the legendary LeBron James—a figure to whom Cleveland’s basketball community is hopelessly devoted—juxtaposed with local talents like Kenny Gregory and Esteban Weaver, whose paths have diverged from James’s due to personal and systemic obstacles. Through these players, Abdurraqib scrutinizes the complex relationships between individuals and the communities that simultaneously nurture and neglect them, highlighting the dual role cities play in both fostering and failing to offer support, security, and respect.

The book is also one of Abdurraqib’s most intimate pieces to date, structured around narratives of his own coming-of-age in Cleveland. “I am afraid of what getting under the hood of this moment will reveal about my own messes—the ones of my past and the ones that are surely on the horizon,” he writes. “I don’t learn from my repeated heartbreaks as much as I learn to catalogue them, to pull them from their cases and admire them with a type of fascination for a while before locking them away again.” Abdurraqib chronicles his own myriad devotions throughout, showing readers how they have shaped him into the person he is today.

Our conversation covered—among other topics—the writing process behind There’s Always This Year, fasting for Ramadan while on tour, and the themes, places, and states of mind to which Abdurraqib returns.

~

Shereen Lee: It’s such a joy to be speaking with you today. I’m catching you for a conversation just as you’re about to head on tour for There’s Always This Year. How are you feeling about it?

Hanif Abdurraqib: I haven’t been on a tour in real life since 2019, which for me is a long time. I can feel how different I am. Not just the impacts of linear time and age and all that, but—I think like a lot of people, if I’m honest—I’m less eager to leave the house. The comforts of my home are a bit more robust. There’s a way that I am anxious about leaving and going on tour. But the thing that’s overriding that is a really pure, just extreme excitement—and a chance to animate this book that has been in my head for so long.

It’s a gorgeous piece of writing, and I’m glad you get to celebrate this way. I’m curious: What’s on your road trip playlist?

I like to do this thing called 12 Tracks, where I make little 12-track playlists throughout the day, all based around themes. And I’ll just kind of make those as I go, you know: love songs that reference rain, or songs about dancing that don’t say the word “dancing”—really hyperspecific. That builds me up. I have this playlist called Driving In Circles At Sunset that is about three hours long, and that’s always the thing that gets me set on tour. When I started going on tour, that’s what I was doing. A playlist that is made to feel like you’re driving in a circular loop while the sun is setting. That is what I need.

I’m curious about how you arrived at the themes of There’s Always This Year, and how those concepts percolated for you. Did you think that you were going to write the book that you ended up publishing?

The origin point of all of my books so far has just been: something that drags me to the page. Something that kind of allows me to pursue the work. When I get to the work, the work transforms and tells me what it needs or wants to be.

I first dreamed this book up in early 2018, and I thought I was going to be writing a book about Ohio in the age of LeBron James. I’m about the same age as him; we grew up playing basketball in Ohio at around the same time; there’s some depth in the similarities in our lives. Obviously, there are also just massive, massive differences. But I wasn’t thinking about that. At first, I was just thinking about Ohio in the era of LeBron James, whatever that meant.

It became more interesting to me when I started to think about those differences. What I was actually thinking about is the question of who gets to make it and who doesn’t, and what it means to make it, and what making it even represents in the scheme of loving a place—and loving a place so much that you don’t want to leave it. But in order for those things to come out, I think I needed to actually do the writing.

Taking to the writing allowed me to say: “Oh. It turns out that I am also—unbeknownst to myself—writing about the passage of time and mortality and the kind of fear that comes with aging and being grateful for that aging, but also being aware of the toll that aging can take. Not even physically but actually just plainly, emotionally.”

A very striking feature of the book for me was how you structured it into the four quarters of a basketball game and print a countdown timer that ticks down throughout the narrative. How did that form develop?

I really wanted to offer people the shape of a basketball game. I don’t think the book is all that much about basketball, but having that physical shape, I think, can convince people that they are in the throes of something that they aren’t necessarily in the throes of day-to-day. It presents this kind of urgency: a hybrid of real urgency and an imagined frantic urgency. I think the book is trying to get into a sort of performance pace, adding real time markers to it.

You have a beautiful line that I’ve been thinking about since I first read it. “With enough repetition, anything can become a religion. It doesn’t matter if it works or not, it simply matters if a person returns.” Can you tell me more about what things you return to, and how they interact with each other?

I’m from the Johnny Cash school of thought. Johnny Cash, early in his career, was like, “I’m going to write three kinds of songs: love, God, and murder.” The reality is that those themes are broad, and large things fit under those umbrellas. It’s up to us as the writers to manoeuvre the many possibilities that exist within whatever themes we choose.

Very early on, I realized that mine would be grief, place, and devotion. Devotion is such a broad one because I think it, in some ways, encompasses the other two. Those will be the things that I am going to be returning to, whether or not I am deeply intentional about it. That’s just the way my brain is wired. My brain is wired to perhaps steer myself toward an examination of one of those overarching themes and asking myself, what can I fit underneath them? What is this pursuit telling me? What is the pursuit telling me this time out? I’m always asking myself those questions. I’ve been really lucky to be able to push myself to a kind of flexibility with those things.

Do you think people participate in devotion for the sake of devotion, or is there something more to it? Does religion play a part in how you see devotion?

I don’t know if I believe in devotion for the sake of devotion. I think my pursuit and investment in devotion means that devotion always has to be acting for the sake of something, even if it is something that has not revealed itself to me yet. I do think that it does return to faith, because I was raised Muslim and I think that there is a very material drive, in turn, toward devotion in the Islamic faith—in all faiths, really—but I’m saying I grew up praying, or the expectation was to pray five times a day. You can touch the material impact of the devotion that’s being asked of you. I think I’m curious about that.

I live a life of returns. I live a life of ritual. I’m very disciplined. Well, I’m pretty lazy overall—I would rather do nothing—but my commitment is not even to what I love, as much as it is to the disciplines that I’ve built around the pursuit of the things I care for. I think that that does feel somewhat religious to me, or it’s summoning a religious motion that I know and understand well. And so the motion, as it manifests itself to me, is maybe not explicitly religious all the time. But I think it’s driven by, or at least informed by, a faith-based relationship.

Speaking of ritual, are you participating in Ramadan now?

Actually, I am. And my Ramadan life is bizarre because I don’t really break any of my routines. I just move the times around. So, like you know, I’m a runner, and I take my reading seriously. So now I just get up at four thirty in the morning; I run, do my eight miles. Then, I eat, hydrate, eat, hydrate again, and then go back to sleep for a couple hours. And then, I start my day. But the challenge of Ramadan for me right now is that so much of the process, I think, relies on decentring oneself. In thinking about how you can better be a version of yourself that does not centre your own needs and wants and focuses, instead, on things outside of yourself. And so, it’s coming out of a strange time for me to have to do this, in a moment where I am—

Going on tour.

Yeah. But I’m looking forward to these kinds of internal examinations bearing external fruit. Or at least, inshallah, bear external fruit. That is something that I hope to see as the year goes on.

A challenging thing about fasting for me is how unsettled and alone I can feel during that process of decentring. Do you feel that at all, especially at times when you’re away from home?

Of course, there are ways that we fast alone, but we also don’t fast alone. You know what I mean? I say that because we’re acting in solidarity with the full body, you know, the full body of the ummah is fasting. I think fasting is a solidarity action. I am driven by the fact that I feel like I am actually not alone. Which is why I have such a hard time making up days, you know.

People ask me if I’m going to make up days because of the rigours of being on tour while fasting. I’m not, because I think that there’s actually something really rejuvenating and renewing to me about saying: “Okay, I’m fasting in solidarity with a full body of people who I don’t know, who don’t know me. We are doing this in this kind of unspoken community.” That gets me through my Ramadan.

For you, does the fierce devotion you experience for others in general have to be earned, in a way, or is it unconditional—as in, something you do because of who you are, because you can’t help yourself?

It’s just a part of my makeup—my mental and emotional makeup. I think devotion and obsession are simply passengers in the vessel of curiosity. I think that these are things that are informed by my nature to be eagerly curious. I think devotion and obsession kind of come out of that now. Not all things are equally moving for me, at all times. But I see curiosity as a vessel through which I like to love more deeply and think more deeply about the people I love and think more critically about the places and things I love. And that, in some ways, can afford me a somewhat clear conscience at the end of the day.

The concept of ascension is a theme that I loved following in the book as well, and I think it’s linked to devotion in a way. Do you think of devotion, maybe, as the harvest that someone reaps from ascension in the beholder’s eyes?

I don’t know. I think it can be, but I also think that it depends on the who, the when, and the where. If it’s a celebrity or an athlete or someone I have no actual personal connection with, that’s one thing. But I think it is beautiful to watch people in my life ascend in many different forms and many different definitions of the word. My devotion or affection for them has not changed or shifted. It’s been the same, for these people I know and love.

How do you feel when you experience a moment of ascension yourself?

To me those moments come with a renewed clarity. I am seeing the world differently than when I saw it in moments prior; a new door has been opened for me. If I am hearing the world differently—if I’m slowing down and being observant of the sights and sounds of a familiar place that is literally unfamiliar to me, through my looking upon it—it feels like I’ve moved past a version of myself that was not capable of seeing the world the way it was. It even rewires my brain, my ears, my eyes to be newly observing a world. That’s really where I feel like I’m settling. It doesn’t happen intentionally, much like my writing process. But through that pursuit of what I’m excited about or interested in, things open up for me.