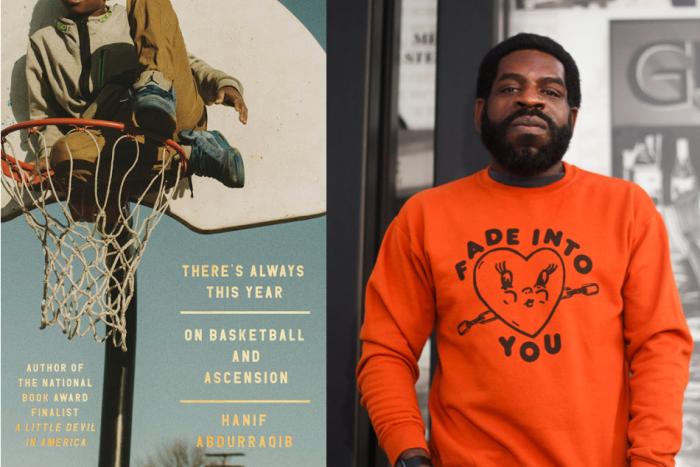

What’s the difference between mazes and labyrinths? Proverbs and adages? Clementines and tangerines? You’ll find the answer to at least one of these questions in the following excerpt from Eli Burnstein’s Dictionary of Fine Distinctions (Union Square & Co.). Charmingly illustrated by cartoonist Liana Finck, peer into the world of the ultra-subtle and—at long last—parse the meaning of thrice removed.

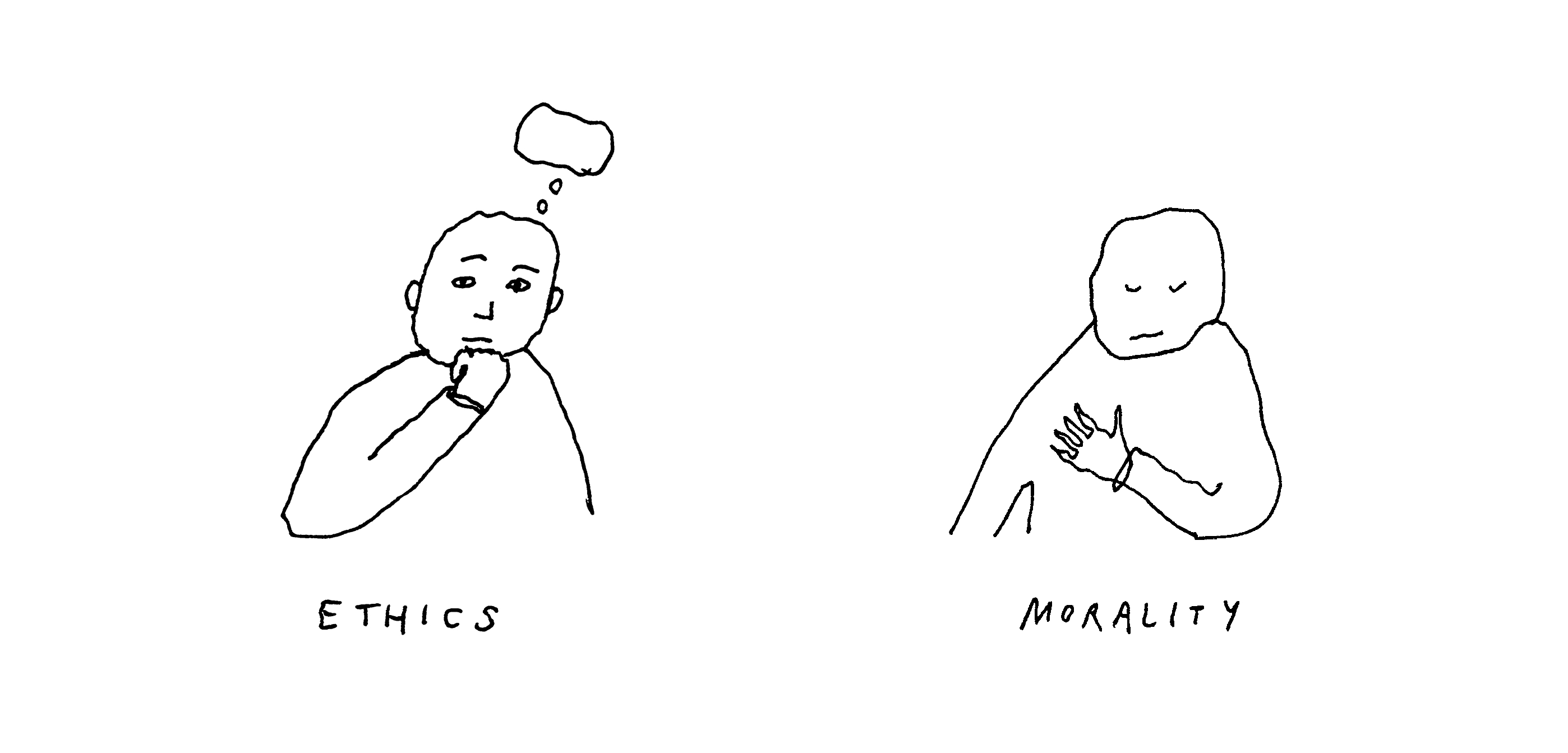

Ethics vs. Morality

Ethics refers to intelligible principles of right and wrong.

Code of ethics

Workplace ethics

Morality refers to right and wrong as a felt sense.

Moral compass

Moral fibre

One is rational, explicit, and defined by one’s social or professional community; the other is emotional, deep-seated, and dictated by one’s conscience or god.

That’s why an immoral act sounds graver than an unethical one: One may get you fired, but the other could land you in hell.

The Fine Print

With characteristic sass, usage master H. W. Fowler notes that “The two words, once fully synonymous, & existing together only because English scholars knew both Greek & Latin [ethics being Greek in origin, morality Latin], have so far divided functions that neither is superfluous...ethics is the science of morals, & morals are the practice of ethics.”*

While Fowler is here alluding to ethics as a branch of philosophy, the conceptual flavor of the word can be heard in its everyday sense as well: Whether theorized by Aristotle or spelled out in a code of conduct, ethics is morality, as it were, with glasses on.

* H. W. Fowler, A Dictionary of Modern English Usage, 1st ed. (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1926), 152.

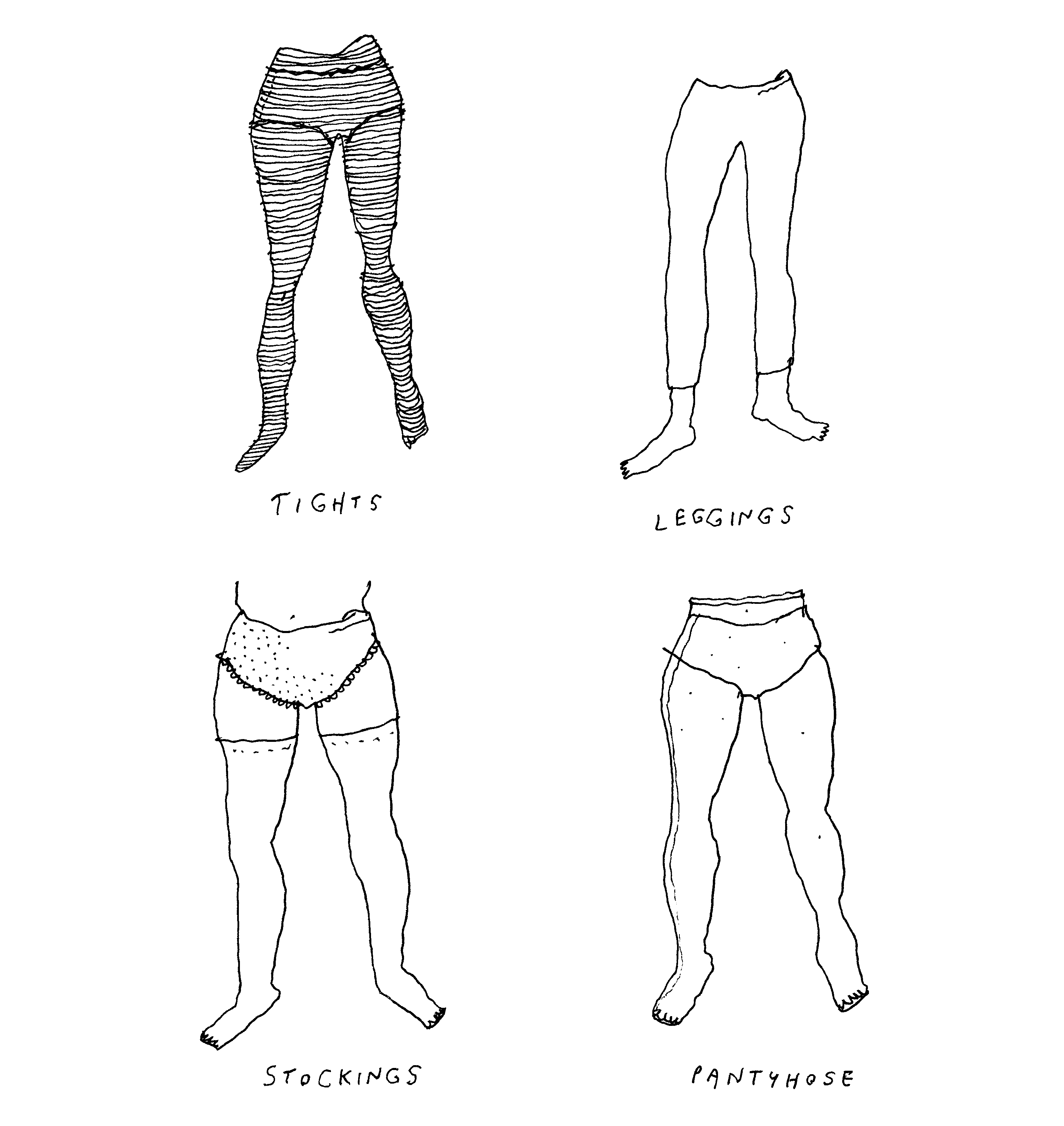

Tights vs. Leggings vs. Pantyhose vs. Stockings

Tights cover the feet. Leggings, as their name suggests, don’t. Tights are also an undergarment and so tend to be thinner and somewhat sheer, whereas leggings can be thicker and worn as pants all on their own.

Pantyhose are an extra-sheer form of tights, often with more opaque fabric covering the upper or “panty” portion of the panty/hose combination that their name suggests.

Less common today, stockings are detached undergarments that stop around the thigh. Sort of like the ones hanging over the fireplace at Christmas.

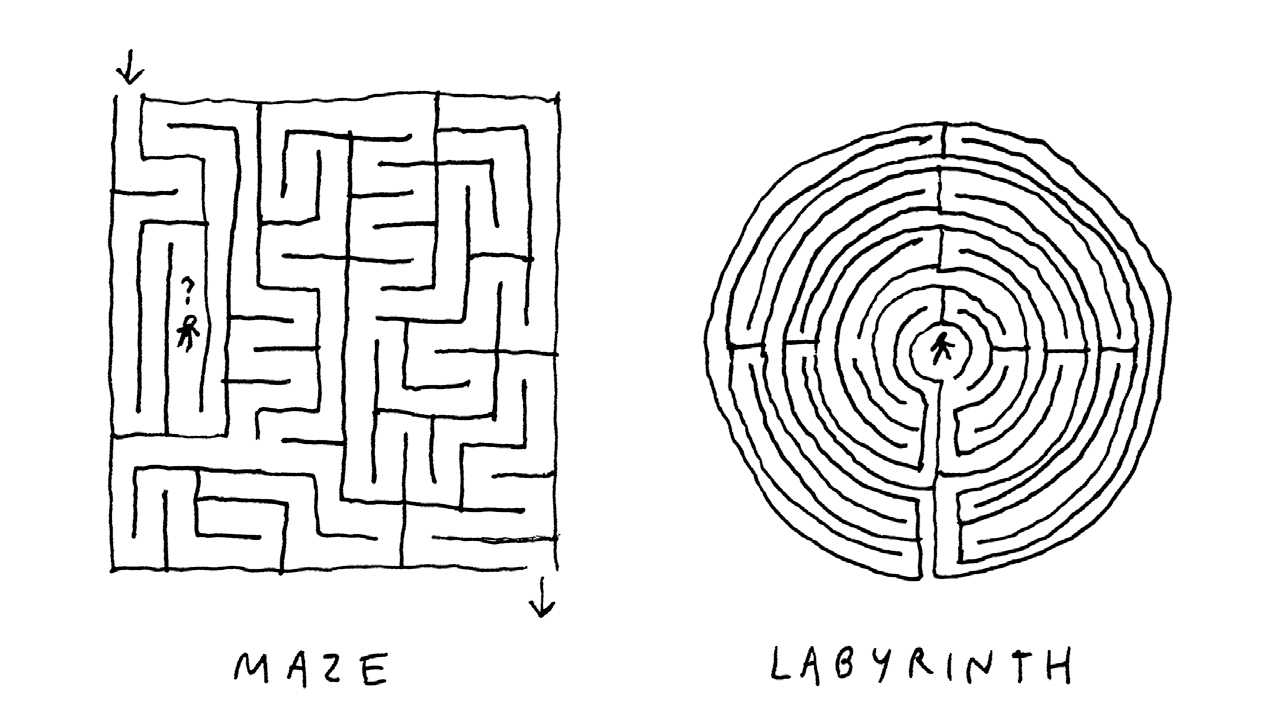

Maze vs. Labyrinth

A maze has many paths and challenges you to find the exit.

A labyrinth has one path and draws you toward its centre.

One is a puzzle designed to challenge and amuse. The other is an exercise designed to calm down the mind.

Walking in Circles

Labyrinths have served a variety of ritual and religious purposes over the millennia, from traps for evil spirits, to burial grounds, to crucibles of personal transformation and symbols of the path to salvation. Wherever they pop up, the idea, in part, seems to be that the repetitive and uncomplicated motion of walking in spiral-like formations can bring on a relaxed, even contemplative frame of mind. Hence the labyrinth’s modern therapeutic appeal.

EXCEPTION

The eponymous labyrinth of ancient Greek mythology—the one with the ferocious Minotaur in its depths—is, in descriptions by classical authors, pretty obviously a maze. Otherwise, why would Theseus need to retrace his steps with a length of thread after slaying the monster? Shouldn’t it be easy (albeit tedious) to get out?

Verdict

Greek namesakes notwithstanding, there remains a meaningful difference between a forking navigational game that’s riddled with dead ends and a winding hypnotic track that isn’t. Mazes refer to the first kind of object; labyrinths, alas, are a bit either/or.

SARAH: You’re a worm aren’t you?

WORM: Yeah, s’right.

SARAH: You don’t by any chance know the way through this labyrinth do you?

WORM: Who me? Naaah, I’m just a worm.

—From Labyrinth (1986)

Endnote

For further discussion on the historical discrepancy between written descriptions of the labyrinth as many-pathed (or multicursal) and its visual depiction on coins and mosaics as single-pathed (or unicursal), see Penelope Reed Doob, The Idea of the Labyrinth from Classical Antiquity Through the Middle Ages (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990). Also, yes, technically, mazes can have centres as their goal (e.g., England’s Hampton Court Maze).

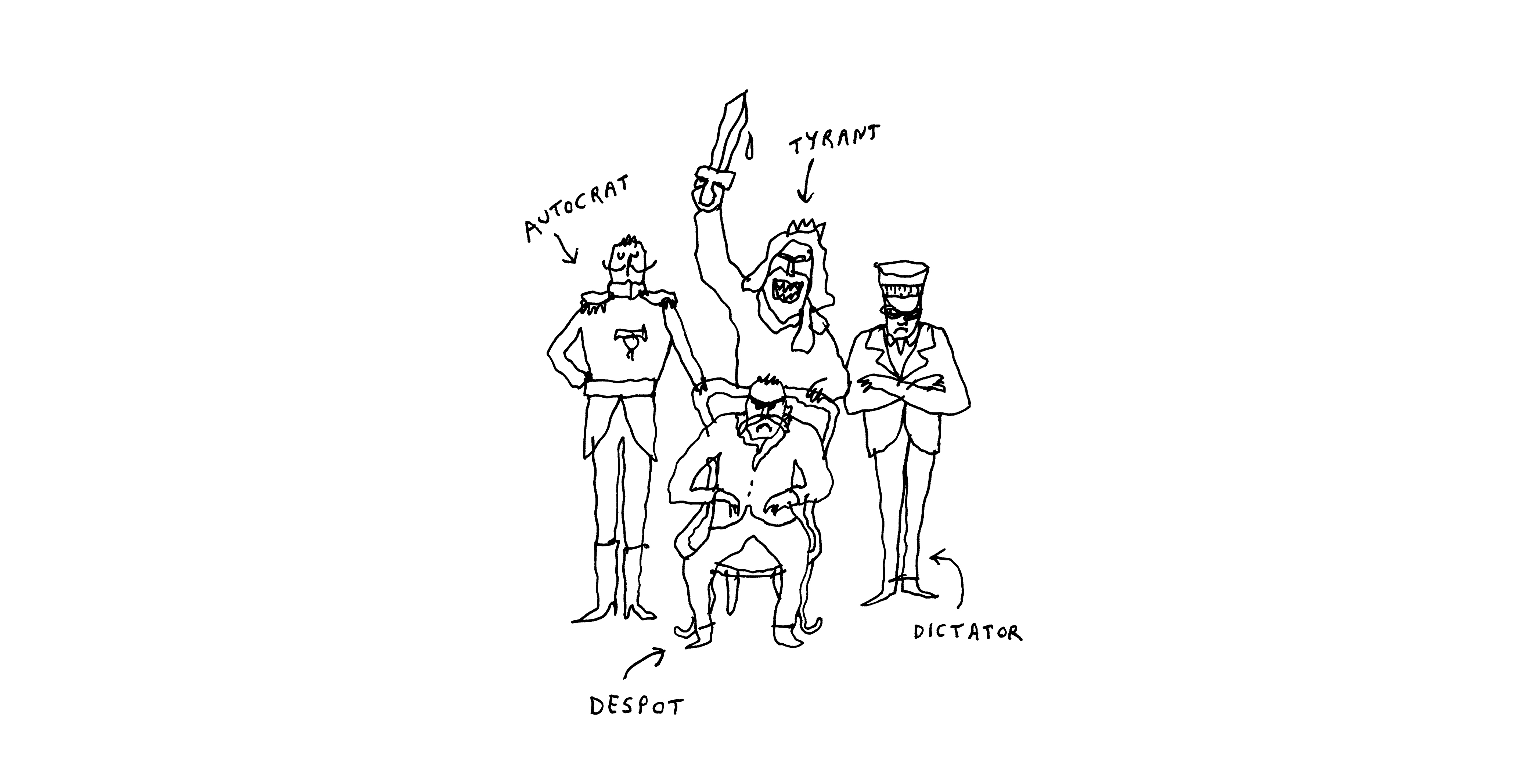

Autocrat vs. Despot vs. Tyrant vs. Dictator

Autocrats rule with absolute power. Despots rule with absolute power cruelly and oppressively. Tyrants rule with absolute power cruelly, oppressively, and illegitimately (usurper). Dictators rule with absolute power cruelly, oppressively, and under a newly established regime.

The Fine Print

• An autocrat rules with absolute power by legitimate means, often within a long-standing or established political system such as a monarchy. Of the four terms, autocrat carries the least negative connotation, though it’s still widely considered undesirable.

ARCHETYPE: Czar Nicholas II of Russia

• A despot rules with absolute power by legitimate means, but oppressively so, and often within a long-standing political order where the domination of the ruler and the unfreedom of its people is the norm. Carrying a regrettable hint of orientalism, the term has historically been used by Western nations in reference to leaders of countries elsewhere—a counterpoint, as it were, to the freedom of one’s own state.

ARCHETYPE: Pharaoh Ramesses II of Ancient Egypt

• Unlike the first two rulers, whose sovereignty is sanctioned by law or custom, tyrants are illegitimate usurpers, seizing the reins by nefarious means. And while despots may hold entire peoples under their thumb as a matter of course, tyrants add an extra measure of frenzied, paranoia-fueled cruelty toward perceived rivals and political threats.

ARCHETYPE: Macbeth, King of Scotland

O nation miserable,

With an untitled tyrant bloody-sceptered,

When shalt thou see thy wholesome days again...?

—Macbeth, act 4, scene 3

• A dictator, finally, rules with self-legitimizing power within a recently established (rather than long-standing) political order, which is why a dictator is typically not a monarch (tyrants aren’t so picky). Here, too, cruelty and oppression are the norm, drawing on ideology, propaganda, and militarization to convert its people from the old way of doing things to the wholly new regime.

ARCHETYPE: Adolf Hitler, Führer of Nazi Germany

ORIGINAL MEANINGS

In the Roman Republic, the term dictator referred to an individual temporarily granted extraordinary powers in a state of emergency—but when Julius Caesar was pronounced dictator perpetuo, the original meaning of the term was perverted, prefiguring the doublespeak of modern dictatorships (e.g., “president for life”).

Tyrant, meanwhile, originally referred to usurpers but not necessarily bad ones—maybe they deposed a despot.

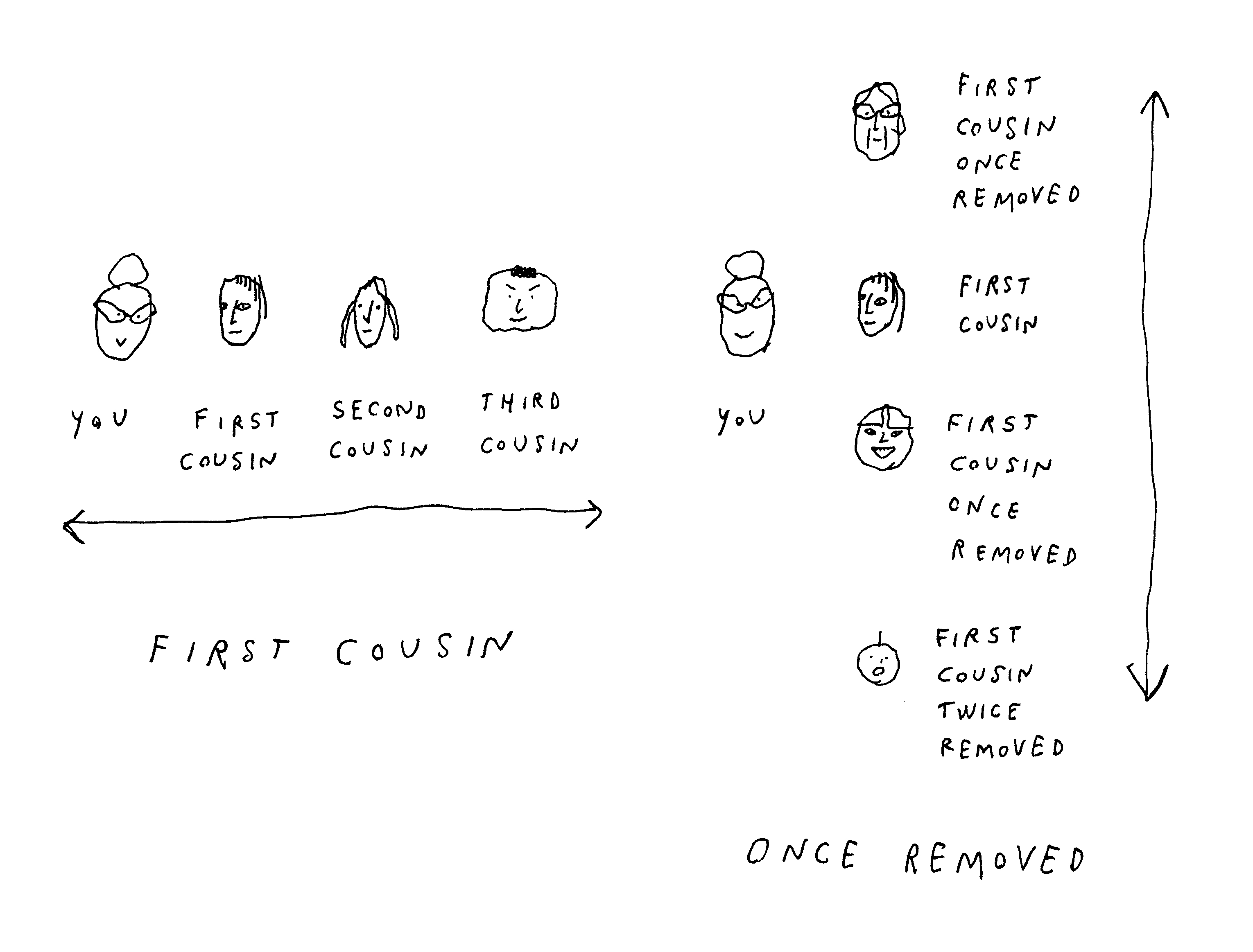

First Cousin vs. Once Removed

First cousins have the same grandparents. Second cousins have the same great-grandparents. In general, degree of cousinhood is determined by distance to a common ancestor.

Once removed means you’re a generation apart. Twice removed means you’re two generations apart. In general, degree of removal is determined by the generational difference between the two cousins themselves.

In short, when you hear “third cousin,” you’re about to meet someone you’re barely related to, but when you hear “thrice removed,” you’re about to meet someone astoundingly old.

MNEMONIC 1: HORIZONTALITY

Cousinhood is horizontal. Removalhood is vertical. If you don’t hear the word “removed,” you’re in the same generation.

MNEMONIC 2: THE G RULE

To establish degree of cousinhood, simply count the number of g’s before finding a shared ancestor: Same grandparents? First cousins. Same great-grandparents? Second cousins. And so on...And if you’re of different generations, simply pick the smaller number of g’s between you: If my grandparents are your great-grandparents, we’re first cousins—and because of the single generational difference between us, we’re also once removed.

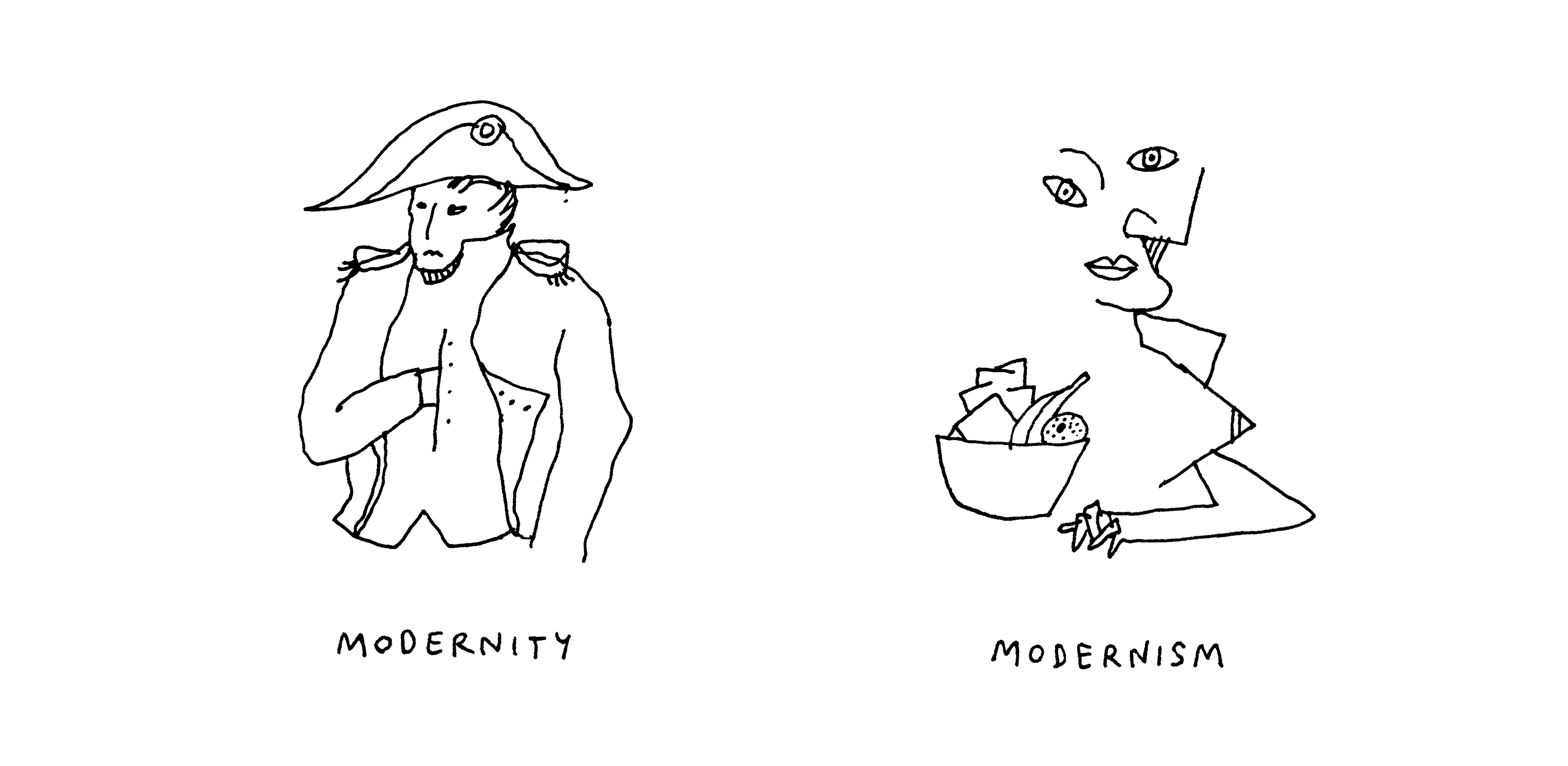

Modernity vs. Modernism

Modernity is a historical period.

Modernism is a cultural movement.

The Fine Print

Modernity refers to the period roughly spanning the mid-1400s to the mid-1900s, though some historians start later or extend it to the present day. Whatever your dates, the idea is that modernity generally refers to the post-medieval world—a world that gradually became more rational, urban, industrial, individualistic, secular, capitalist, and liberal. What follows modernity is sometimes called the contemporary period, though in lay contexts both modern and contemporary roughly mean nowadays as opposed to the past, or up-to-date as opposed to old-fashioned.

Modernism, by contrast, is a literary, artistic, and philosophical movement that was in vogue from roughly the 1890s to the 1940s. Modernist works are characterized by a fascination with novelty and the desire to break with the past; a fragmented sense of time and space; a preference for creativity over imitation; and formal experimentation. Notable modernists include Virginia Woolf (stream-of-consciousness novels), Pablo Picasso (cubism), Arnold Schoenberg (twelve-tone technique), and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (International Style architecture).

Excerpted with permission from Dictionary of Fine Distinctions © 2024 Eli Burnstein, illustrations by Liana Finck. Published by Union Square & Co.