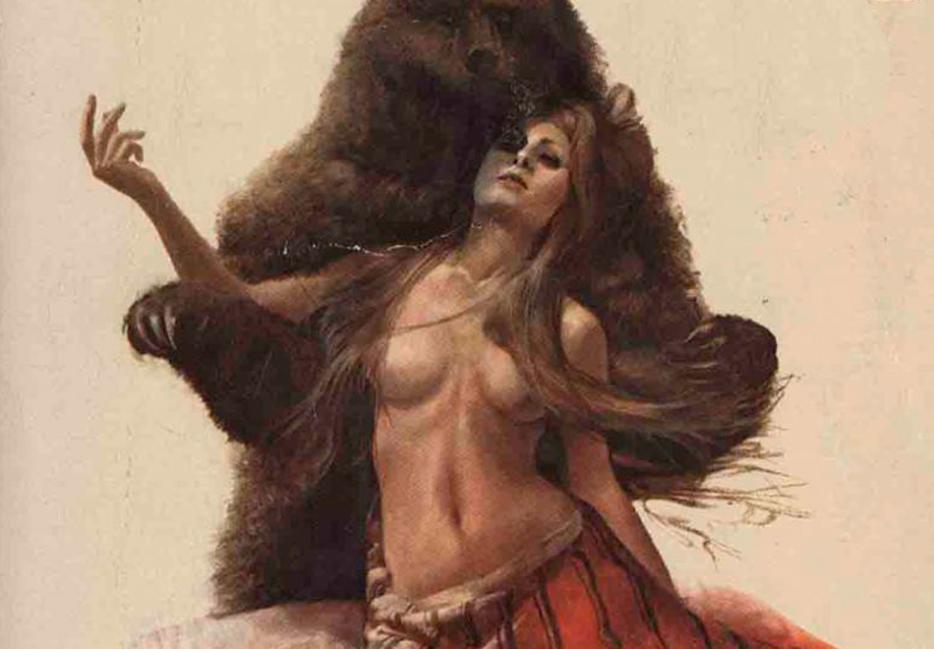

To celebrate Bear, we asked five illustrators to reimagine the novel's startling 1976 cover.

The first thing you need to know about Marian Engel’s 1976 novel Bear is that it is about a woman who has sex with a giant bear. Not a metaphorical, figurative, concept-within-a-creature bear: a real, furry, wild brown bear. There’s more to it than that, but why bury the lead?

The second thing you need to know, however, is that this is not some fringe underground chapbook: it won the Governor General’s award—the highest Canadian honour for the literary arts—in a year in which the jury included Mordecai Richler, Margaret Laurence, and Alice Munro.

We’re talking about Bear right now, though, because someone recently posted its cover and some particularly raunchy sections of the book to Imgur under the title, “WHAT THE ACTUAL FUCK, CANADA?” There was even a little boost in e-book sales after the book’s cover—an illustration of a lithe, topless woman with flowing brunette locks being embraced from behind by a bear standing on its hind legs—went viral. It looks like a Harlequin romance novel: ursine Fabio and his eager human companion, lost together, alone in a world that will never understand the depths of their potentially life-threatening interspecies love.

The story, ultimately, is not as sexy as all that, though it’s not without its moments of high erotica. It begins with a librarian named Lou heading to an island in remote northern Ontario to catalogue the library of an estate bequeathed to the institute for which she works, and, as luck would have it, finding a bear living on the property. Their affair truly blossoms two-thirds into the book, though, when, one night, she’s lying by the fire with the bear, feeling incredibly lonely. Overheating, Lou takes off all her clothes and proceeds to “make love to herself,” as women are wont to do. The bear, apparently knowing how to take a hint, starts to lick her—as bears are wont to do.

As the bear begins to survey the landscape, Lou remarks upon his “moley tongue,” which is, “as the cyclopedia says, vertically ridged.” (Ever the librarian, our Lou—her head in the books even as the head of Stephen Colbert’s number one threat to America is between her legs.) After a few laps, Lou begins to emit little horse-like “nickerings,” and goes on to call the episode, on the whole, “warm and good and strange.” This is probably as accurate a description as possible of the experience of reading Bear. It’s remarkably poetic: “Bear,” Engel writes, “take me to the bottom of the ocean with you, bear, swim with me, bear, put your arms around me, enclose me swim, down, down, down, with me.” And, “Bear, I cannot command you to love me, but I think you love me. What I want is for you to continue to be, and to be something to me. No more. Bear.”

As time goes on, Lou realizes she’s in love with the bear. Bear, being a bear, does not reciprocate her feelings. Is there a more total rejection than being turned down by a wild animal? He can’t even get an erection for her, “his prick [not coming] out of his long cartilaginous sheath.” In one desperate moment, Lou pours honey on herself to entice the bear to stay. “Once the honey was gone,” though, “he wandered off, farting and too soon satisfied.” It’s possible to see Lou, who has had bad luck with men in her past, as a stand-in for Engel herself, who was going through a divorce of her own while writing the book, imbuing it with equal parts empowerment and loneliness. Bear is dedicated to “John Rich—who knows how animals think.” John Rich was Engel’s psychotherapist at the time.

As time goes on, Lou realizes she’s in love with the bear. Bear, being a bear, does not reciprocate her feelings. Is there a more total rejection than being turned down by a wild animal?

Canadian Literature is sometimes prematurely marginalized in the minds of readers for its supposed over-reliance on rural narratives and abundance of stories about humans at some sort of critical or bittersweet impasse with nature; imagine a CanLit drinking game in which you have to empty your glass every time you read the words, “the sound of the loon cry.” But Bear subverts the cliché: here, after all, is a woman actually getting down on all fours and presenting herself to an animal, almost as if to say, “You think we love nature? Oh, I’ll show you how much we love nature.”

Bear garnered largely favorable reviews upon its release, finding support among respected writers and editors. As Canadian novelist, playwright, journalist, and fellow GG winner Robertson Davies wrote in a letter to Engel: “I’m fearful that the book might not be taken as seriously as it is intended and that you might be exposed to comment and criticism of a kind which, in the long run might not be helpful to you.” Considering the context of the book’s current moment of Internet fame, it’s tough to argue with Davies’ assessment. One notable pan at the time came courtesy of the critic Scott Symons, though, who, in his West Coast Review essay “The Canadian Bestiary: Ongoing Literary Depravity,” called the book “spiritual gangrene… a Faustian compact with the Devil.”

But if the book were all bear-on-broad action, it wouldn’t have the resonance it does today. It’s not simply a bizarre bestial farce; it’s a modern Canadian fable, an ironic play on romantic pastorals, and, above all, totally readable. Margaret Laurence wrote in praise of the book, calling it “fascinating and profound… [a] moving journey toward inner freedom, strength, and ultimately toward a sense of communion with all living creatures.” It won the Governor General’s award because of the strength of its writing, and because it challenges the reader as much as it strikes an emotional chord. It was published towards the tail end of second-wave feminism in North America, as women’s sexual empowerment was being pushed to the foreground; it wasn’t just gonzo—it was the zeitgeist. Recently, author Andrew Pyper wrote a defense of Bear, recommending it to readers “not because it’s a feather ruffler of a book ... [but] because it brings something to the conversation that wouldn’t be spoken if we didn’t read it, if we kept things strictly appropriate. Bear is brave. We should be too.”

The book was far from Engel's only significant contribution to CanLit. None of her other novels were quite as noticed or acclaimed, but the small group of Toronto writers that organized the Writer’s Union of Canada did so on her front porch in 1972; she was elected chair at its formation, and spearheaded the Public Lending Rights, which gave authors and editors payment for their titles in library circulation.

Engel died in 1985; we’ll never know how she might have felt about her sudden burst of Internet fame, four decades after the fact. But her place in history is secure: a friend to publishing, an award-winner alongside the authors of The Diviners, The English Patient, and The Stone Diaries, and a woman who, one day in the tumultuous 1970s, sat down, and, with full command of her craft, wrote of a lonely librarian in love with a bear: “She cradled his big, furry, asymmetrical balls in her hands.”