...for it is the fate of a woman

Long to be patient and silent, to wait like a ghost that is speechless,

Till some questioning voice dissolves the spell of its silence.

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1858, as quoted in Alias Grace

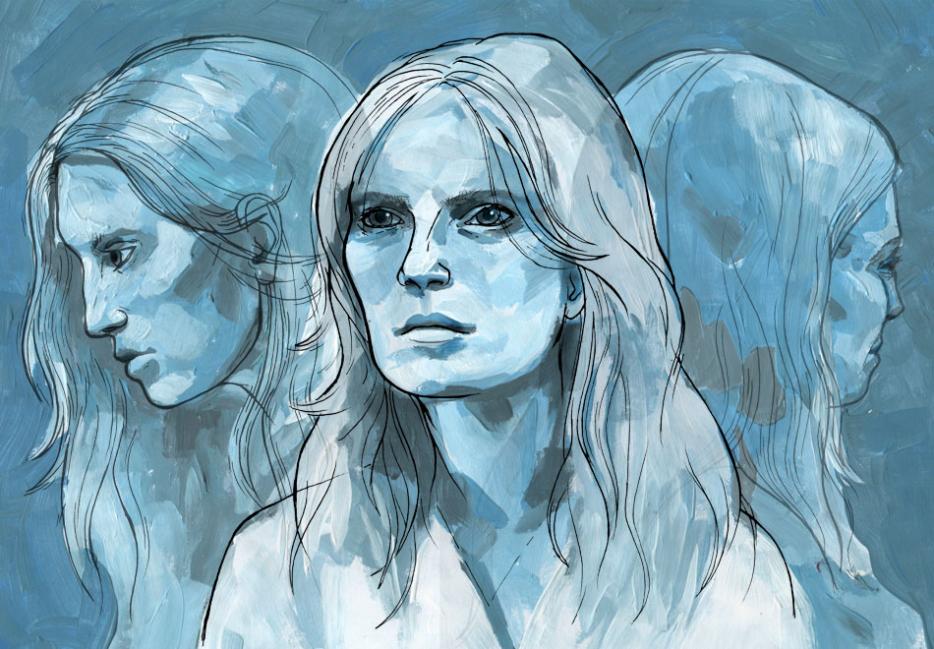

Alias Grace opens on Grace Marks’s reflection. Actress Sarah Gadon, as the “celebrity murderess” who may or may not have killed her employer and his housekeeper in 1843, wears little makeup, her hair in a white bonnet, her collar white too, grey-blue top matching grey-blue eyes. Her spartan accoutrement redirects our focus entirely to her countenance as we watch it flicker from one expression to another, floating along the waves of Grace’s narration:

I think of all the things that have been written about me...that I am of a sullen disposition with a quarrelsome temper, that I have the appearance of a person rather above my humble station, that I am a good girl with a pliable nature and no harm is told of me, that I am cunning and devious, that I am soft in the head and little better than an idiot. And I wonder, how can I be all of these different things at once?

Alias Grace was published in 1996, an almost six-hundred-page factual-fictional account of the life of a real sixteen-year-old Irish-Canadian servant girl. Through the eyes, ears, mouth, mind of Grace and her psychiatrist, through their conversations and correspondences, writer Margaret Atwood forms a picture of Grace’s transformation, over thirty years, from guileless maiden to keen convict. But what to believe? Are these memories real? Is Grace the person she presents to the world? Does she even know who she is?

Sarah Polley knew. At seventeen she read Alias Grace and saw herself in Grace Marks. Also young and famous and motherless, Polley too had difficulty knowing who she was, difficulty separating herself from the image others had of her and the image she had of herself. It follows, then, that the stories this Canadian filmmaker has chosen to tell—Away From Her, Take This Waltz, Stories We Tell and, most recently, Alias Grace (which she wrote and produced), as well as her next adaptation, Zoe Whittall’s The Best Kind of People—are also about women whose identities are in flux, who are knocking against a collective memory they no longer fit, who are searching for who they truly are. As Alias Grace’s co-executive producer Noreen Halpern says of Polley, so too could she say of Polley’s heroines: “She really is a woman who is so many facets of woman.”

I. The Actor: “I was shut up inside that doll of myself.” – Alias Grace

Sarah Polley’s parents were actors and, according to a family legend memorialized in the New York Times, as a young child she would grab their scripts and demand auditions. By the age of five, she had already made it to the big screen, as a penniless kid in the movie One Magic Christmas. Within three years, Polley was starring in Terry Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, in which she played the daughter of a theater director staging a production of the 18th-century nobleman’s Don Quixote-esque wartime exploits. “It wasn’t just a story, was it?” her character asks. Polley told Maclean’s that the role’s demands—periods in frigid water, proximity to deafening explosions—persuaded her to avoid epic productions in the future.

That same year, 1988, Polley became known in her hometown of Toronto for playing the title role in the 10-part CHCH adaptation of Beverly Cleary’s Ramona books, a series about an imaginative child whose curiosity lands her in countless compromising situations. In an interview with The Globe and Mail at only eight years old, Polley said that she “sort of” believed she was her character because she had played her for so long. “I liked the way Ramona stands up for herself,” she said. “She’s not a noisy or a mean girl, but I like the way she’s so brave and has trust in herself.”

But it was not until Road to Avonlea that Polley became “Canada’s sweetheart.” The loose adaptation of L. M. Montgomery’s less famous novel revolved around a ten-year-old heiress who loses her mother and, when her father is accused of embezzlement, is sent to live with relatives in P.E.I. where she insinuates herself into the lives of the town’s locals. From 1990 to 1994, Sarah Polley was inextricably tied to Sara Stanley, not only in name but in story—she had also lost her mother.11Polley was 11 when her mother died of cancer. “I was in a daze, a very happy childhood daze, and basically I came out of it the second my mother died,” Polley told Maclean’s. Like Grace Marks, unlike Sara Stanley, she did not grieve according to convention. Rather than retreating inside herself, her response was to look outside. “All of a sudden people became fascinating to me,” she said. “I became very aware of people being three-dimensional, and having motives and angles.”

Polley left Road to Avonlea in her mid-teens, admitting later to Toronto Life that the danger she felt on the set of Baron Munchausen had already “hardened” her, “isolated” her. “As a child, it’s a complicated thing to be forming your own identity while your job is to pretend you’re somebody else,” she told The Globe and Mail in 2007. “Especially for a girl, having generally older men constantly congratulating you for becoming who they want you to be.”

Having developed scoliosis the year her mother died, for four years she wore a brace that had to be concealed under her costumes. After a ten-hour operation, Polley spent a year in bed recovering. Then she quit acting. Perhaps, like Grace, who had not yet determined who she was before being imprisoned, Polley saw the risks of stasis. “That happens in the Penitentiary,” Grace says, “some of them stay the same age all the time inside themselves; the same age as when first put in.”

II. The Activist: “If God alone knew, then God alone could tidy it up.” – Alias Grace

Sarah Polley dropped acting for activism. During the Gulf War, in protest, she wore a peace sign to an American awards ceremony. Disney, which had picked up Road to Avonlea for U.S. distribution, reportedly asked her to remove it. Polley did not. “I don’t think I ever had any big transition where I decided, ‘I’m not going to be an actor, this isn’t what I want to do with my life,’” she told the CBC at the time. “I just sort of always knew that it wasn’t my thing.” Polley claimed she had always just acted for fun and that she now had an actual vocation: activism. Appearing on the Canadian teen talk show Jonovision, she said, “I feel passionate that there shouldn’t be inequality in society.”

So, in her mid-teens, Polley quit school to, as she told The Globe and Mail, “become a political activist and have more time to read.” She handed out leaflets for the Ontario New Democratic Party and, in a protest she helped organize against the provincial Progressive Conservative government, famously lost two back teeth in a fracas with the police. Polley also supported the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty, speaking out against income inequality, and in 1994 considered studying political science and philosophy at the University of Oxford. Says Brian D. Johnson, a contributing editor at Maclean’s who has known Polley for two decades, “For somebody in showbusiness who’s really smart and who has ethics and principles, she [might have seen fame] as a sort of vast diversion from what really matters in the world.”

Polley traced her activism in part to “middle-class guilt,” she told The Globe and Mail in 1996, but she came by her socialism honestly. Her biological father, Montreal film producer Harry Gulkin, was a communist who had also dropped out of school, in his case to join the Merchant Marines before becoming a union organizer. And Polley’s mother, Diane, and the father who brought her up, Michael, supported such values—one of her older brothers even worked for the NDP, enlisting his little sister to leaflet for him. “Being out of kilter with society in some way, a bit of a rebel—that was thought of as a necessary part of being a citizen, being in a dialogue with the world,” Polley told The Globe in 2007. So, she swore like a sailor and fought for equality, the reformed sweetheart’s response to the disparity of an industry she knew so well.

III. The Star: “…what is there to celebrate…?” – Alias Grace

Sarah Polley flits back and forth onscreen at eighteen between child and adult, adult and child. As Nicole Burnell in The Sweet Hereafter, she plays a girl sexually abused by her father, and also a woman who hates him for it. “Nicole is who I am internally in a lot of ways,” she told Maclean’s at the time, acknowledging the empowerment girls claim in the presence of men. “I probably acted it out a lot more with men on the set, when I realized that crawling into their laps had a certain gravity to it.” In her most celebrated scene in the film, Nicole leans on her father before standing up to him, wrapping a lie in a lie—Polley not only performs a lie in the shape of Nicole, but, within that performance, Nicole also lies in order to expose thetruth. She told Johnson that this was the first time her acting was taken seriously. “Having been an actor so much of her life, for the first time she was acting really as an adult,” he says.

Until then, Polley had dabbled in roles that slyly subverted her immaculate persona—the maybe-prostitute in Atom Egoyan’s Exotica, the goth girl in the series Straight Up—but she got serious in The Sweet Hereafter. “I guess the realization came from watching [co-star] Ian Holm act, and just recognizing that there’s something about the human contact you have when you’re acting with somebody who’s really looking at you, and you’re really looking at them,” she told Women’s Wear Daily. “That became completely intoxicating to me.” Before this, she had not considered herself particularly talented at performing, admitting she simply “toyed with” different sides of herself. But, despite her growth, there remained a purity to her acting. “She’s kind of incapable of giving a dishonest performance,” says Johnson. “She’s so transparent. She can do nothing and you can kind of read into her soul through those eyes.”

Those Uma Thurman eyes, those eyes that narrowly avoided the cover of Maclean’s in 1997 (Princess Diana had just died). “[Polley] was dressed down for it,” Johnson says of the shoot. “On the other hand, you look at her eyes in that shot and, boy, she’s on.” And Hollywood couldn’t stop staring. Following the premiere of The Sweet Hereafter at Cannes in May 1997, Saturday Night reported talk of a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nod, and, by 1999, Polley had officially become an “It girl.” That year she sent a frisson through Sundance when she appeared as Stephen Rea’s protege and much younger lover in indie overlord Miramax’s Guinevere and as mercenary drug dealer Ronna in Doug Liman’s Go. In the latter, however, she seemed oddly out of place, a mound of fertile earth among the garish blooms of teen paraphernalia—Katie Holmes, Scott Wolf, Breckin Meyer—and the bright lights of a derivative pseudo-Tarantino party. But she took the role because of her politics, she told Saturday Night, because of this exchange between her checkout clerk and a mother on welfare:

Mom: Don't think you're something you're not. I used to have your job.

Clerk: Look how far it got you.

Polley read it as recognition of society’s failure to live up to its citizens. Instead it played as a glib punchline at the expense of the poor—it played the opposite of her politics. “Everyone is only interested in themselves and getting more money and being completely reckless,” she said of the film in the aforementioned mag. “To an American making that film, that’s a celebration.” And, as a part of it, she was too.

The cover of Vanity Fair, the cover of Interview, gushing call outs in The New Yorker and Rolling Stone and Premiere and Esquire followed. “I think it’s really important to emphasize that it wasn’t just a matter of celebrity,” says Kay Armatage, co-editor of Gendering the Nation: Canadian Women’s Cinema, “it was a matter of really great valued work that she had done.” All eyes were on her and Johnson remembers Polley telling him she was nervous when he asked her to present a prize at the Toronto Film Critics Association gala. “She was obviously in love with the art of [acting], but she was wary of the celebrity thing,” he says. “Being a child actor, I think she recognized it was a kind of imprisonment in a way...”

And she rattled her shackles loudly. In 2006, Toronto Life reported that Polley once “threw a fit” over her Vanity Fair appearance as the magazine credited their advertiser, Tommy Hilfiger, with the vintage jacket she wore on its cover. “I’ll help sell the movie, but I won’t help sell Versace or Calvin Klein or smear makeup on my face,” she told The New York Times in 1999. That same year, she said in Women’s Wear Daily, “…I’m just too busy freaking out about who the hell I am when I’m not around cameras, you know? I don’t have time for figuring out how other people perceive me. I want to know what I think of myself first.” Her reaction perhaps hewed to where she was brought up, the place where she became famous first: Canada. “Canadian fame is that comfortable level of fame, but once it goes above a certain velocity I don’t think it’s that much fun anymore,” Johnson says. “Like anybody who is seduced by the spotlight, if you're going to stay level-headed, you've got to be suspicious of that.”

So Polley became guarded with the press, mentioning to Toronto Life that she had read Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer (about the ethics of reporting), considering interviews only if the journalist recorded them, hiring a publicist to “protect” her. In The New York Times in 2007, she described herself as “a really gregarious, loud person,” who would find herself becoming subdued during interviews, “playing a role of myself instead of myself...”

Then she stopped. At the time, Cameron Crowe had cast her in Almost Famous and for weeks she rehearsed as Penny Lane, a groupie who falls in love with the frontman of a ‘70s rock band. “The part didn’t fit me,” she told The New York Times in 2007. “Every day, it felt less and less like something I could pull off.” So she quit, leaving behind the movie that would have given her Kate Hudson’s life, a life populated by People magazine covers and paparazzi. “I realized I don’t want that,” she explained to Toronto Life in 2006. “I want to be completely in control of the choices I make.” But it was more than that. Last month, following the first allegations against Harvey Weinstein, Polley wrote an op-ed for The New York Times about the Miramax producer propositioning her when she met him while working on Guinevere. "I loved acting, still do," she wrote, "but I knew, after 14 years of working professionally, that it wasn’t worth it to me, and the reasons were not unconnected to the tone of that meeting almost 20 years ago."

That didn’t mean she knew what she wanted to do next and, after turning her back on Penny Lane, she fell into a depression. Her response was reminiscent of Grace Marks’s when she is finally set free, after three decades, into a world where nothing and no one is waiting for her: “So now, instead of seeming my passport to liberty, the Pardon appeared to me as a death sentence.”

IV. The Director: “And inside the peach there’s a stone.” – Alias Grace

Sarah Polley saw The Thin Red Line in 1999. Terrence Malick’s spiritual meditation on war—what it does to us, how it brings us together and pulls us apart, how we transcend it—changed her life. “It shifted something in me,” she toldToronto Life. “I’m an atheist, but…it gave me faith in other people’s faith.” She had no idea films could do that. She wanted to do that. “An actor is a filmmaker on a certain level,” says Johnson, “but not usually a filmmaker with control …” Polley had nevertheless made inroads. On The Sweet Hereafter, she had collaborated with Canadian director Atom Egoyan, not only acting in the film, but also writing some of the music as well as performing it. “That’s being more than just the talent, that’s more than being an actress,” Johnson says. “She was already thinking like a filmmaker. Atom, I think, was her entré into filmmaking.”

Post-Almost Famous, Polley had an idea for her own film. Within a month she wrote and shot the first in a series of shorts about long term relationships and, with that, she fell in love with filmmaking. She also had talent. Polley graduated from the Canadian Film Centre’s directing program in 200122Eight years later she would graduate once again in documentary filmmaking. and only two years later won a Genie Award for her short I Shout Love. The following year saw her first adaptation, an episode in a mini-series based on the work of Canadian author Carol Shields. Polley added a broken relationship to the short story “The Harp,” about a woman who loses a piece of bone after she is hit by the titular instrument. “Why does everything end so badly?” the heroine asks, before her father, hearing impaired like Polley’s (who plays the father in question), mishears harp as heart. “A heart is a relatively soft and buoyant organ,” he says. “You’ll get over it in no time.”

Polley’s first feature, her second adaptation, was also based on a story by a Canadian woman, was also about a woman being reconfigured. Away From Her (2006) centered on Alice Munro’s short story “The Bear Came Over the Mountain,” about a man (Gordon Pinsent) whose marriage of four decades dissolves when his wife’s (Julie Christie) Alzheimer’s sends her away from him and into the arms of another man. Polley later surmised that her own father’s experience of losing his wife subconsciously dictated her connection to the story. “[T]he most affecting emotional experience of my childhood was watching my dad lose the love of his life,” she said in Maclean’s in 2007. There was the theme of memory, too—it was not only her dad who lost someone—the seeds of which would germinate later.

Adapting the work of others made sense for Polley, who had already demonstrated her aversion to self promotion. John Galway, president of the Harold Greenberg Fund, which provided financial support for Away From Her, Take This Waltzand Alias Grace, says, “A short story is really a starting-off point and then you expand the story out to become a two-hour feature, whereas often with a novel it’s actually about what you take away.” In both cases, the story is the anchor, allowing for easier control.

Controlling the set was harder. Polley told the Toronto Star that she was an uptight director because she feared failure, feared losing the support of her crew, which she remembered from the sets of other first-time filmmakers. “You know as an actor so acutely what destroys morale, what creates complaints, and that can be good and bad, because when you’re directing you can become hyper-aware of that,” she said. The approach worked and her first effort was nominated for two Oscars: best adapted screenplay and best actress.33She lost the screenplay nod to the Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men. “When she did Away From Her, it was a revelation to everybody how good she was as a feature film director,” says Armatage, who is also a professor emeritus at the University of Toronto in the Cinema Studies and Women and Gender Studies institutes. “I think that her own career as an actor has everything to do with her talents as a director. When you look at Away From Her and Take This Waltz, for two, the performances of those two women in the leads are extraordinary.”

Take This Waltz (2011), Polley’s second feature, has Michelle Williams playing a wife in a happy marriage who is nonetheless dissatisfied and falls for an artist. The script was not an adaptation, and Polley repeatedly stated that it was not based on her 2008 divorce from David Wharnsby (she married doctoral law student David Sandomierski a month before the film premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and the couple now has two daughters). “I think in that case she wanted to challenge herself with coming up with an original story,” Galway says. Though the characters were younger, once again here was a woman re-establishing her identity, balancing reality and fantasy (a rickshaw driver-artist who can afford a loft that big in Toronto could only be make-believe). In one scene, Margot (Williams) sits on a carnival ride next to the man she is falling for, “Video Killed the Radio Star” booming, flashing lights blinding. Then the music abruptly stops, the fluorescent glare returns, and the tin can ride and concrete floor are revealed in all their colourless banality. This unveiling is something of a Polley signature, a former star grounding herself in reality. Polley told the National Post in 2012 that her psychiatrist had once said to her: “Life has a gap in it.” She had wanted to make a film about that gap ever since. “Since I was about 19 or 20, I’ve been thinking about these things, which is why every short film I’ve ever made, as well as Away from Her and this movie, are about long-term relationships,” she told the Post, adding later to the same paper, “I’ve been making films thematically about my parents in various ways...”

V. The Daughter: “I would like to be found.” – Alias Grace

Sarah Polley had grown up hearing the joke, how she looked nothing like her father, how her mother must have had an affair. The question of her paternity would punctuate her life until her late twenties, often preceding a transformation. First, from actor to activist in her mid-teens; then, after the jokes became more specific (was her father in fact actor Geoffrey Bowes?), from actor to star at around twenty; and finally, from star to director in 2006, when she found out that her biological father was not Michael Polley, the man who had raised her, but Lies My Father Told Me producer Harry Gulkin.

There were five years between Polley confirming her biological father’s identity and the 2012 release of Stories We Tell. Her documentary was inspired by the various interpretations—from family, friends—of the events and weaves together their memories and perspectives to create a kind of tapestry of the past. “I think the uncertainty of a basic objective truth is in my films, and that’s part of me as a Canadian. That’s a cultural thing that has been handed down to me,” she told the Toronto Star in 2014. “That there’s not one truth that everyone must obey, but that there are different realities for everyone.” Using real home videos intermingled with fake archival footage that she filmed on Super 8, Polley’s previous films re-emerged like prophesies, the opening scene, a grainy image of her mother, recalling the opening of Away From Her (“I never wanted to be away from her. She had the spark of life”); the mid-movie revelation that some of the home videos had been shot by Polley herself harking back to the revelation of Take This Waltz’s carnival scene. And the title, Stories We Tell, from a passage in Alias Grace:

When you are in the middle of a story it isn’t a story at all, but only a confusion; a dark roaring, a blindness, a wreckage of shattered glass and splintered wood; like a house in a whirlwind, or else a boat crushed by the icebergs or swept over the rapids, and all aboard powerless to stop it. It’s only afterwards that it becomes anything like a story at all. When you are telling it, to yourself or to someone else.

What emerged was a portrait of a woman not unlike Sarah Polley and not unlike the heroines she gravitated towards: “[Diane] was always trying to get out from under anything that she felt controlled her or made her feel like her life was very regulated,” says one of her sons in the film. “I wanted to share my experience of hearing the different versions and the way they were converging and diverging,” Polley told the Globe in 2012. “And to let the audience have the experience of being the observer—being me.” Despite this being her own story, the story of how she came to be, Polley consciously excluded a sit down with herself. But every scene, every shot, every fade, was evidence of her perspective, her own identity refracted through the film, just as it refracted through everything she had already made. “Before this I hadn’t realized that I was mining stories from my own life,” she told Film Comment in 2013.

VI. The Writer: “Or the story must go on with me…” – Alias Grace

Sarah Polley had a teacher in grade two who let her write all day. As a kid, Polley never considered writing for film. But then, at seventeen, she read Alias Grace. “To be a woman in that time, or any time, there are parts of your personality and responses to things that you’re expected to suppress,” she told The New York Times last month. “So what happens to all that energy and all that anger? What do you do with powerlessness? The idea of having more than one identity, the face you show to the world and the face that’s deep within, captivated me.” It was the first film she wanted to make, the story of a young woman whose mother died too soon, who became a celebrity without setting out to, who was imprisoned, who couldn’t parse the truth out of the past, who couldn’t even parse herself.

At first, she thought she might produce it and maybe play the title role. Then she realized she had formed every image of the book in her mind. She wanted to adapt it. Polley chased the rights in her teens, but according to The Globe and Mail, Margaret Atwood’s agent thought she was too inexperienced to handle them. She kept an eye on the book over the years and, following Away From Her, the rights were hers. So, after making two films and two babies, she started writing. "Screenwriting allows for so much more reflection and solitude," she told University College Alumni Magazine in 2012. "I think it’s my favourite part of the process because everything is still possible and not mitigated by the exigencies of production.”

The result was too long for a film, but short enough for a mini-series. Polley sent her six scripts to Noreen Halpern, the CEO of Halfire Entertainment. The producer thought the story of an elusive nineteenth-century servant who may or may not have committed murder, whose memory could not deliver her, was a seamless extension of Polley’s oeuvre. “I knew how much Sarah has always been interested in perspectives,” Halpern says, “who people are, how they present to the world, memory, how memory can be true, how it can be false, how it can be twisted in a way that isn’t even true or false, it’s just how memory changes over time.”

At a meeting at By the Way cafe in Toronto, Polley said she would not direct. “She didn’t feel she was the best person suited to direct this,” says Halpern. “That maybe is the producer side of her taking control.” Polley suggested Mary Harron instead, the Canadian director of American Psycho, who she had always admired. Halpern agreed, as Harron “has always been able to deliver visceral images that are very much tied to character.” The duo eventually sold the project to two other women, Sally Catto at the CBC (Canada) and Elizabeth Bradley at Netflix (the U.S.), the former being particularly gratifying. “I spent my childhood on the CBC, this bucolic vision of this time that never existed in this country,” Polley said in The Globe and Mail earlier this year. “As nice as it was for families to watch, it was a bit of a lie. So to be back on the CBC in this brutally honest look at what it was like for women in period costumes, and people get spattered in blood, was extremely cathartic.” Fittingly, the last word in the series, said by Grace’s dying doctor, is her name, “Grace.” Her identity finally confirmed, Grace breaks the fourth wall, shatters the chasm between us, leaps from our collective memory into the present: I am here, her look says.

This is Grace Marks. This is Sarah Polley.