On a good day, to someone like me, superheroes are a juvenile distraction, like deep throating a box of Nerds when you’re old enough to know better. On a bad day, they are a capitalist virus, multiplying across the culture and eclipsing everything in their path. Maybe it’s conceivable for one good guy to destroy one bad guy, but how does one person—even one person with all that power—fix a world whose enemy is itself?

The day I spoke to Supergirl, May 30th, a global pandemic had pushed the American death toll past 100,000, protests had broken out across the country over the killing of yet another Black man, George Floyd, and the U.S. president had tweeted, “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.” It sounds like the ideal setting for a superhero to suddenly materialize and clean house, but that’s not how it works. One bad apple is not responsible for this dystopia, this is a corruption embedded in our soil.

So maybe it was the world that was cloudy and not the Zoom call that was blurry when I spoke to Helen Slater. Either way, she looked mortal in a way I didn’t remember her in 1984, when she starred in the first ever female-led superhero movie. Instead, I remember her in Supergirl as white blond, bowl eyed, diaphanous, the kind of soaring Aryan beauty that can only be created in captivity, or at least with a lot of bleach and blusher (“I’m Jewish,” Slater says). More than 30 years later—me 40 and not 4, her 56 and not 19—Slater’s hair is still long and light, but it isn’t white. She wears heavy-framed glasses that she keeps punching up her nose. She says her daughter is teaching her about fourth wave feminism and that she is studying mythology. Slater is grounded in California, but she may as well live right next door. Because at this moment she is as impotent as the rest of us.

White supremacy, patriarchy, transphobia, every other phobia—the roots of inequality have so invaded the core of society that the very notion of a single solution, let alone a superhero to provide it, is not just a fantasy, it’s an affront to reality. And yet we are overrun by superheroes. They are predominantly white men, though some superheroes of colour have recently emerged; more persistently celebrated, however, seem to be the women, most of them white, as though female-led superhero films are the last bastion of feminism. And with the December release of Wonder Woman 1984, it’s impossible for me not to think of Supergirl, which was released in 1984, two stories with identical time periods made thirty years apart. It’s impossible not to think about how much has changed and how much hasn’t. Women still don’t own superheroes, of course, but are superheroes even worthy of them?

***

You would think that the decision to make the first female-led superhero movie would be a monumental one. You would think that, but only if you thought that way. The kind of people who think that way aren’t usually the kind of people who make those kinds of decisions. Businessmen make those kinds of decisions. And, sure, some businessmen are culturally inclined, some can think abstractly. But a lot of them don’t. A lot of them think in money and that’s it. In Hollywood, those kind of businessmen (and they are usually men) care about movies insofar as movies mean box office. A good movie makes good money, a bad movie doesn’t. Those are the kinds of men who made Supergirl. “For us, as producers,” Ilya Salkind told Film Comment in 1983, “the point of making a film is that moviegoers looking through the newspaper pages in any big city will want to see . . . one film!”

The Salkinds were a kind of producing family dynasty. Grandfather Mikhail worked with his son, Alexander, the money guy, and his grandson, Ilya, the creative one, on The Three Musketeers and The Four Musketeers. It was on that set that Alexander, whom Ilya described to me as “crafty” with money, became infamous for being the first producer to shoot two films at once (the Salkind Clause was subsequently created by the Screen Actors Guild to keep one contract from being stretched across two projects). In 1974, Alexander and son were looking for a new project when, out of the blue during dinner one night, Ilya said: “Why don’t we do Superman? He’s got power, he flies, he’s unbelievable!” To do that, the Salkinds had to get the rights from DC Comics. Ilya called the process a “pain in the ass” involving months of negotiation and even a draft of the script. In the end, though, they secured the rights to Superman for twenty-five years. And not just Superman.

Supergirl isn’t as old as Superman. Kara Zor-El first appeared in Action Comics in 1959, two decades after her cousin, as a kind of secret sidekick with similar powers—superhuman strength, speed, flight. While she was created by men, she did enter an industry already occupied by Wonder Woman. And if Superman is the Übermensch, Wonder Woman is the Überfrau. She is the female superhero against which all other female superheroes are compared. It’s common knowledge now that psychologist William Moulton Marston created Diana Prince (who was drawn by suffrage cartoonist Harry G. Peter) in 1941 as a kind of catch-all antidote to comics’ toxic masculinity. She appealed to lefties because she was an immigrant from an all-female island encouraging women to use their powers to act in solidarity for peace. She appealed to righties because she was a conventionally attractive white cisgender heterosexual who uses violence to get her way. “She combines multiple ideologies in one body so anyone can see in her what they want to see and that’s I think what makes her so popular,” explains Professor Carolyn Cocca, author of Superwomen: Gender, Power, and Representation, and whose latest book Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel: Militarism and Feminism in Comics and Film was released in August.

Supergirl had to wait until the late Sixties to become the lead, by which point feminism was in its second wave. This culminated in Gloria Steinem throwing Wonder Woman on the cover of Ms. Magazine in 1972. Four years later, the most accessible female superhero in the world would get three seasons of her own television show, with a couple caveats. As producer Douglas S. Cramer put it, “She should be built like a javelin-thrower but with the sweet face of a Mary Tyler Moore.”

That would be Lynda Carter. In her starry trunks and scarlet bustier, both of which got skimpier as the seasons progressed, her Wonder Woman became the iconic female superhero. Despite the character’s activist origins, however, ABC didn’t take her particularly seriously. Wonder Woman was clearly satirical. It had a super cheesy theme song—“In your satin tights,/fighting for your rights”—used comic book-style speech bubbles, and its pièce de résistance was a ridiculous transformation involving a slow-mo beep-laden twirl. “Please, whatever you do, don’t ask me what I think of women’s lib,” Carter told Orange Coast Magazine two years in. “I’ve heard that question so many times I could scream.” It was a good way to avoid explaining why the first time we see Diana, she is running through a jungle in a gauzy pastel teddy and big hair like she’s in Valley of the Dolls. “There’s a reason it’s called jiggle TV,” says Cocca. “There’s a lot more running than you need to see.” Which is not to say Wonder Woman did not touch on feminism—it couldn’t really avoid it. “Any civilization that does not recognize the female is doomed to destruction,” Diana says in the pilot. “Women are the wave of the future and sisterhood is stronger than anything.” It’s just that she says it while torturing the woman beside her.

***

Superman III was “a disaster.” Ilya tells me this no less than three times, with the same flattened gravitas each time. It was bad enough that the Salkinds chose to start a Supergirl franchise instead of continuing with Superman—it seemed to be less about wanting to make Supergirl than about not wanting to make another Superman. Everything about the way Supergirl was made signaled her second-class status. While the budget for Superman was $55 million, the budget for Supergirl was $35 million. While the director of The Omen made Superman, the director of Jaws II made Supergirl. While Christopher Reeve was paid $250,000 for Superman and Superman II (amounting to $125,000 each), the actress hired to play Supergirl was paid only $75,000. When I brought up the comparatively low fee to Ilya, he remained unfazed: “I mean, she was totally unknown.”

That part is true. Helen Slater had just graduated from a performing arts high school when one of her agents put her forward for Supergirl’s best friend while the other suggested her for Supergirl. “I don’t want to go up for the friend, I want to go up for the lead part,” Slater remembers thinking. So, her mom sewed her a costume, including a cape. “I remember feeling very self conscious that I had maybe gone too far,” she says. But she had brought a copy of Moby-Dick to the audition because she was supposed to be reading it during her scene and she remembers casting director Lynn Stalmaster commenting on that. It was one of the “little sign posts” that told her she was doing well, despite the nerves. To get an idea of what all of this looked like, you can find images online from Slater’s 1982 screen test. Despite the big hair, the cheesy red headband, and the bib-like cape, she looked as earnest as she would on screen.

The moment Slater was cast as Supergirl was actually caught on film because a documentary was being shot around the production. “I probably cried, right?” she says. No, she didn’t. She appears surprisingly poised, in fact. The footage shows Slater being called into an office, ostensibly as a farewell, when the news is sprung on her. “It seems you have the part,” she is told. “Really?” she says. “Oh my gosh. Oh my God. Alright.” Slater explains that she came from a school that considered theatre the be-all, not television or film. She didn’t think she was the best actress, nor did she think this was the best part. But she knew it was big. “The feeling was just so much excitement that I might be able to make a living at this,” she says. In press from the time she looks perpetually awestruck. In behind-the-scenes footage, she is wide-eyed. Slater was so wide-eyed, in fact, that she didn’t question the quality of the script (“You feel you’ve been chosen for something,” she explains, describing her younger self as “compliant”). Nor did she question Faye Dunaway being given first billing. Presumably Dunaway was also paid a lot more, though Slater doesn’t begrudge her own low salary: “For me, that was more money than I could ever imagine.”

Though Slater grew up in a “broth” of strong women—an activist mom, an academic step-mom—she was only 19 when she was cast as Supergirl. And this was the Reagan era, the era of the conservative backlash to second-wave feminism. As Slater put it, “I still felt so much of my identity and what mattered was how men viewed me.” To get an idea of how they viewed her, consider People Magazine’s December 1984 issue. In an article titled, “My Dinner with Supergirl,” Scot Haller writes about Slater’s chest growing though workouts and inquires whether she thinks Supergirl has sex. “What a strange question,” the actress replied at the time. When I bring up the interaction during our interview, Slater doesn’t remember it. What she does remember is making the film itself. “It had a male director, it had a male writer, it was male producers,” she says. “It was very female diminished in a lot of ways.” Set footage bears this out, showing a good number of the male crew on set (including director Jeannot Swarcz) shirtless in jean shorts. In the middle of them all, Slater is in head-to-toe Supergirl regalia diligently performing her duties.

“Helen’s beautiful, but not threatening to other women,” Ilya said on the Supergirl press tour in 1984. It was another way of stating the persistent unofficial rule in Hollywood that all female protagonists must abide by: be relatable. It was actually less about Slater being non-threatening to women, more about her being non-threatening to men—where Superman was strength and power, Supergirl was elegance and style. Whatever feminist gains Wonder Woman, and protagonists like Princess Leia and Ripley, had made, the Eighties’ conservative retaliation against progressive movements as a whole helped ensure that female superheroes didn’t get too fierce. This backlash, the plummeting newsstand sales of comics, the rise in specialty shops to fill the void, and a loosened comics code all converged to create an exclusionary fan base that, according to Cocca, was “older and more male and more white.” This demographic increasingly preferred hypermasculine male superheroes and hypersexualized female superheroes—basically everything they couldn’t have. Moving into the Nineties, comics got even more hostile for women, the art more pornographic, the stories more violent. An Archie reader forever, I remember visiting Toronto's Silver Snail comic shop when I was a teenager in the Nineties. I always felt out of place. And I never went in alone.

***

There was a 20-year gap between the first major female-led superhero film and the second. In the intervening years, the circumstances hadn’t much changed. In 2004, Catwoman was as much of an afterthought as Supergirl had been in 1984. It was also a spin-off, this time from Batman, and, after a decade in development hell, it was rushed into production when another Batman movie—Batman vs. Superman—was dropped. The Batman series had reintroduced Nineties audiences to Catwoman, but director Tim Burton’s retelling was still very much within the realm of comic books’ fantasy world. It was Marvel, first with X-Men in 2000, then with Spider-Man two years later, that relocated superheroes to modern day reality. X-Men may have had three male stars, but it also had four significant female superheroes, most notably Halle Berry as Storm. A year later she would become the first (and only, so far) Black woman to win an Oscar for Best Actress (for Monster’s Ball). Three years after that she would lead her own superhero movie and be the first Black woman to do so. Unfortunately, the movie was even worse than Superman III.

Catwoman shouldn’t be as bad as it is. The budget was a healthy $100 million. A couple of women were behind the scenes this time—Denise Di Novi was one of two co-producers, and one out of its six writing credits was playwright Theresa Rebeck—and the star had just won the most prestigious acting award in Hollywood. Yet somehow all of this still coalesced into a third-rate music video. French director Pitof (yes, he goes by one name) never once lets us forget he is an effects guy, zooming and panning across every scene to the point of regurgitation. The flimsy plot has Sharon Stone fully camped out as a beauty brand ambassador shilling cream that turns your face to rock. Berry, meanwhile, seems to have aimlessly wandered off of the Dolby Theatre’s red carpet into the role of a meek “ugly” graphic designer whose ethereal beauty fails to be constrained by a few errant strands of hair and some baggy tunics. Her self actualisation requires being thrown off a viaduct and swarmed by an army of cats, which turns her into a half-naked wall-climbing femme fatale.

Catwoman paws at feminism—“Catwomen are not contained by the rules of society,” Berry’s character says—but this soft-core fantasy is still bound by the limits of the male imagination. The film is very much an expression of a popular brand of feminism from the early aughts, just as Elektra would be a year later (another spin-off afterthought rush job, this time from Marvel’s Daredevil, with Jennifer Garner playing a bustier-clad assassin). While real activism could be found that year in Washington’s birth control march and in personal blogs by a diverse array of young women, popular culture preferred a more photogenic brand of lipstick feminism. Practitioners performed their sexuality as a means of subverting male strictures on women’s bodies, except that their behaviour happened to play into the very male gaze it claimed to be challenging. As Ariel Levy writes in Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and the Rise of Raunch Culture: “Proving that you are hot, worthy of lust, and—necessarily—that you seek to provoke lust is still exclusively women’s work.” Has a male superhero ever been asked, like Elektra, if he has time to get laid? Female superheroes may be immortal, but the Gods remain men.

The failure of Catwoman and of Elektra became a self-fulfilling prophecy—the work that featured women was not as good, which, as Marvel’s CEO later made explicit, proved that work that featured women was not as good. In the meantime, Christopher Nolan changed the superhero genre for good in 2005 with Batman Begins, followed three years later by The Dark Knight, which gave superheroes real gravitas, which made them worthy of cinema. That same year, 2008, with the brighter, wittier Iron Man, Jon Favreau made certain there would be no turning back. Because of them, Marvel and DC and everyone else was suddenly all about the IP. If you have the good fortune of not knowing what that stands for, it’s intellectual property, which is to say, any idea or character or story that already exists, that has in some sense been tested already (see Batman, see Iron Man, see any other comic book character in existence). And as you run your way down the IP, from the most popular superhero to the least, from Marvel to DC to everyone else, you are working predominantly with male characters because those are the ones that were originally pushed.

Well, DC had Wonder Woman. She had done well on television. In 1976. But a movie? There was no successful precedent for a female-led superhero movie. And Hollywood needed one. Hollywood is one of the most precedential industries around. Even if that precedent is often misguided. “Conventional wisdom is so easily proven false, it’s really a conventional fear,” explains Cocca. “It’s based on how we devalue women so we assume men don’t want to watch women, but we value men, so we assume women will watch men.” Hollywood is risk averse, it needs certainty, at least a little bit, and there was nothing that suggested a woman-fronted superhero movie could be successful. Alien? No, that was a sci-fi movie. Terminator, too. Xena? Buffy? Alias? TV, TV, TV. But female-led superhero movies? They all bombed.

“Where are all the female superheroes to save the world?” Hannah Gill asked in the Scotland Herald in 2004. Three years later, Mother Jones reported on “the new wave of feminist fangirls” who had their own websites and “hate nothing more than when real-life problems like the glass ceiling intrude on their escapist fantasies.” As the aughts chugged along, this generation of feminists brought a backlash to the backlash, signalling that progressive movements were back on track. Online growth meant comics were accessible outside exclusionary zones, and with the boom in superhero movies and series, the audience broadened, conventions became more inclusive, and that more diverse fan base became vocal on social media. “When you put all those different kinds of pushes together you do start to have the hiring of more diverse people behind the scenes,” Cocca says.

That’s where Melissa Rosenberg comes in. In 2010, her gritty series based on the Marvel comic Alias was supposed to appear on network television (a less risky proposition than film). Superhero Jessica Jones had a dead family and functional alcoholism and a knack for investigating. She was also goth hot and super strong and could jump really high. ABC passed in the end, but after Disney ransacked its IP to make a bunch of shows leading up to its mini-series The Defenders, Rosenberg was recalled. Her updated pilot, which has more than a passing resemblance to the hardboiled teen cop show Veronica Mars (precedent!), hit Netflix in late 2015. Jessica Jones starred Kristen Ritter in a hoodie and combat boots and was praised for its handle on trauma.

If Jessica Jones owed The Dark Knight, the new Supergirl TV series owed Iron Man. Set to premiere the same month as Jessica Jones, CBS moved its launch a month earlier. Once again, the show was somewhat reactive, with co-creator Greg Berlanti basing his version of Kara on Ginger Rogers, who “had to do everything Fred Astaire did but backward and in heels.” Like Iron Man, Supergirl is high on gloss and high on quips, though Supergirl herself has the same doofiness Superman did way back in 1978. She also preserves the dregs of male fantasy. Star Melissa Benoist expressed discomfort with her character’s signature micro mini, while Supergirl has often been accused of pandering to feminists. (A little less sophisticated than Jessica Jones, this series includes lines like, “Supergirl? We can’t name her that! Shouldn’t she be called Superwoman?”) But while Jessica Jones was cancelled last year, Supergirl remains afloat (its sixth season, airing next year, will be its last, but a new spin-off, Superman & Lois, replaces it). Television executives seem to prefer their female superheroes in line with their predecessors. That Helen Slater appears in the Supergirl series as Benoist’s foster mom only underscores the proximity of the past.

***

While Superman took place in a big city and a bustling newsroom, 1984’s Supergirl was restricted to a small town and a smaller school. Even its sexism was banal: the heroine narrowly avoids a sexual assault pretty much the second she arrives on earth, her schoolfriend cautions her not to show off her smarts, she is saved multiple times by a himbo, and in the final stand-off, the worst insult Supergirl can conjure up for Selena, the woman trying to kill her, is that the older woman has no friends.

Though planes were flown over Cannes to announce Supergirl just as they had announced Superman, the latter made five times its budget at the box office, while the former made less than half its own. Film critic Roger Ebert seemed genuinely disappointed by Supergirl’s mishandling. “There’s a place, I think, for a female superhero,” he wrote. But it wasn’t 1984. Slater thinks one of the reasons the film didn’t fly was because of the gendered expectations around the genre: “It was really coming up under the veil of the Superman movies and male superheroes.” And while she would have loved for it to have been a success (and, presumably, to have made the two sequels she was contracted for), she wasn’t too broken up about it all. “I remember the feeling being that I’m not going to get stuck the way Chris got stuck,” she says, referring to Superman star Christopher Reeve. “I felt genuinely that I got away with the best possible scenario. The movie didn’t do so great, but I still got in the door enough that I could keep working.”

No wonder 2017’s Wonder Woman took forever to get here. In 2007, a Joss Whedon feature based on the character was reportedly cancelled and, in 2011, a David E. Kelley pilot was, too. In 2013, DC Entertainment president Diane Nelson said that Wonder Woman was a priority but, “we have to get her right, we have to.” While the cancellation of Batman vs. Superman cursed us with Catwoman, Batman v Superman made Wonder Woman possible. Released in 2016, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice was the first time Wonder Woman appeared in a live action film. She took the form of Gal Gadot, who, like Lynda Carter, was a statuesque former model. As an Israeli expat, Gadot (who had also appeared in four Fast and the Furiouses) had served time in the army, a detail both Hollywood and the press couldn’t seem to get enough of. She was a dream come true for the superhero genre: a kick-ass supermodel. And though she appeared on screen for less than five minutes and only had a handful of lines of dialogue (her grunts take up more screen time), she left a lasting impression.

“I think she deserves grand cinema,” director Patty Jenkins says on the Wonder Woman Blu-Ray. Jenkins had in fact pitched a Wonder Woman movie in 2010, a story that centered around Steve Trevor, the pilot who crashes near Diana’s island, but DC passed. Instead they went with an origin story conceived by Batman v Superman’s director (Zach Snyder), one in which Steve acts more as Diana’s chaperone to 1918-era Europe. DC initially hired Michelle McLaren to direct, but “creative differences” sent them back to Jenkins. She pitched Wonder Woman as the ideal universal woman, not unlike Superman for men. She wanted to make something that hearkened back to the first modern superhero film, Richard Donner’s Superman, the implication being that this would be the long-awaited first modern female-led superhero film. And it lived up to the burden. Wonder Woman is exponentially better than any of the female superhero movies that preceded it. It has a better script, better direction, better effects, better acting. It is grandiose, transcending the pages from which it was born, just like Batman Begins, just like Iron Man. But as Wonder Woman’s mother tells her, “Be careful in the world of men, Diana, they do not deserve you.”

There appeared to be a concerted effort not to make Wonder Woman about politics, which is to say not to make it about feminism. That makes sense if you want to appease fan boys, but it makes less sense when you realise fan boys appear to consider any progressive change political. Discrimination is also political. And fourth wave feminism is here whether Hollywood likes it or not. So, when Jenkins says of Wonder Woman, “the idea of sexism is completely absurd to her,” the same cannot be said of Wonder Woman. None of the choices made in the film have been made in a post-sexist world. It says something that the most powerful women on Diana’s island are white and that Diana was not conceived by her mother out of clay (as she was in the comics), but by a man and a woman. It says something that the friends Diana fights alongside are not women (as in the comics) but men, and that the enemy she fights is a man, not a woman (as in the comics). Diana in the film is also quicker to violence—Jenkins has said the most important scene for her was the war scene—than she ever was on the page. In Cocca’s words, “They tried to center this female character but they got nervous about it.”

***

Captain Marvel was designed to be Marvel’s “big feminist movie,” star Brie Larson told Entertainment Tonight two years ago. The film’s release on International Women’s Day in 2019 was in line with this plan. That this release date was the culmination of various scheduling conflicts with male-led superhero films gets closer to the truth. As opposed as its approach to politics was from Wonder Woman and as tonally different as they were, Captain Marvel wasn’t so dissimilar. The heroine here also wore red and blue and gold and was also a soldier and also had a boyfriend in the military. “Both of them are created to be feminist but both of them are also created to be militarist,” says Cocca. Captain Marvel and Wonder Woman are alike for a reason. It’s hard enough, beyond their super powers, to distinguish male superheroes’ individual personalities on screen, but it’s even worse with the women, who always seem to be a generic mix of vulnerability and strength. But either you’re an individual, or you’re an everywoman, and an everywoman has a better chance of representing the underrepresented.

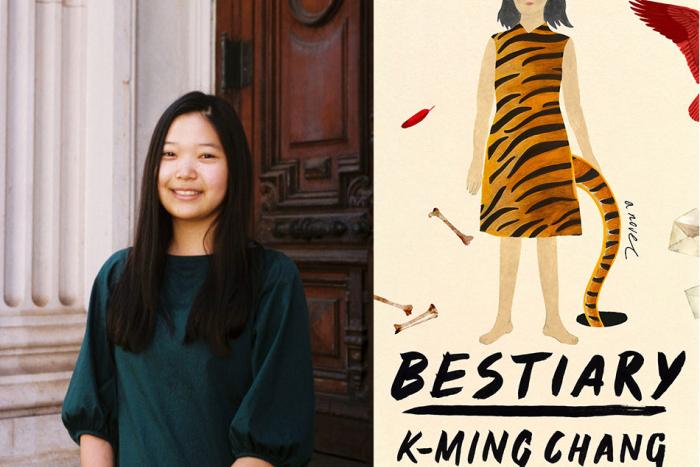

Two months before Wonder Woman premiered, Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck—the duo behind the indie films Half Nelson and Sugar—were announced as the co-directors of Captain Marvel. Boden, the first woman to helm a Marvel Cinematic Universe film, tells me they were fans of the 2013 independent film Short Term 12, in which Larson played a supervisor at a group home, and always wanted to work with her. “It’s her humanity, you know, and how in touch she is with her emotional world,” Boden explains, “and that in combination with a super powerful hero got us really excited to tell a story about somebody who maybe was trying to push that part of themselves down.” At the same time, they didn’t want their movie to be too serious. I asked Boden if that Marvel CEO email from 2014—the one in which Ike Perlmutter cited Supergirl, Catwoman, and Elektra as reasons not to make more “female movies”— was added pressure for them, but she said no. “We felt pressure to make something good,” Boden said. “I think that all Marvel directors feel a lot of pressure to make a movie that is successful because all their movies are successful and you don’t want to be the one that just like completely fails.”

Captain Marvel is good enough. It takes a character that was introduced in 1968 as a love interest and turns her into a fully formed heroine whose pugnacious alien side is at odds with her tender human side. Larson is funny and charming in a way that reminded me of Chris Pratt in Guardians of the Galaxy. The musical cues were similarly jukebox, if a little more glaring—playing No Doubt’s “I’m Just a Girl” during the huge fight scene was a little on the nose—and it does hammer on a lot more than it needs to about Carol Danvers’s mortal sensitivity. Captain Marvel doesn’t announce itself in quite the way Wonder Woman did, but it ultimately passed the billion-dollar mark, even if it didn’t make a huge impact beyond that. Still, it’s hard to gauge exactly why Boden and Fleck are not involved in the sequel; Boden seemed to be weighing her words very carefully when I asked about that. “I can’t say exactly, it’s just that we’re”—long pause—“moving on to doing other stuff.” And then the publicist abruptly ended the conversation.

***

This is supposed to be the year of the female superhero and, maybe so, but what does changing the gender of a well-established genre really mean? From Supergirl to Jessica Jones to Captain Marvel to Wonder Woman, the players may have changed, but the game remains the same: The men made the rules, now the women are just operating within them. Is it even that many women, anyway? While fan outrage makes it seem as though superheroines are taking over, per Cocca, “it’s a really really small change, you know, numerically.” Film, television, comics, each of these media only has women starring in under 20 percent of its titles. That may be a 300 percent growth from a decade ago, but that doesn’t mean the representation is fair, it just means it’s slightly less unfair than it was. Hollywood may want to diversify its audience, but not at the expense of the old one. That means you start with white women, maybe some men of colour, but women of colour? They may make up the majority of earth but they make up the minority in superhero movies.

The only way to keep female characters from being burdened, from being basic, is to have more of them. That way each one doesn’t shoulder all the pressure of representing an entire gender. But to have more of them, there has to be more diversity behind the scenes, so that homogenised groups of executives at profit-oriented companies are not making all the same decisions. “While there are a number of popular, strong, complex female superheroes,” Cocca writes in Superwomen, “in general what we see is underrepresentation, domestication, sexualization, and heteronormativity.” But I don’t want to sound too pessimistic. It is something to go from 19-year-old Helen Slater being given one shot at Supergirl by a man to 34-year-old Gal Gadot co-producing and starring in a four-film Wonder Woman franchise directed by a woman. And despite the pandemic, a number of female-led superhero movies are still set to go in the next few months besides Wonder Woman 1984. Cathy Yan’s recently released Margot Robbie vehicle Birds of Prey was followed in August by The New Mutants, an X-Men spin-off starring Maisie Williams, while Cate Shortland’s Black Widow starring Scarlett Johansson is still on Marvel's slate. Not to mention Chloe Zhao’s Eternals, which will be fronted by Angelina Jolie and Gemma Chang in 2021, and talk around the role of the Black Panther potentially being taken over by Letitia Wright following Chadwick Boseman's sudden passing. Female superheroes are so in vogue right now it’s virtually impossible to keep on top of which ones are coming when and how and with whom in charge.

But in case you’re getting too excited, as one of those barely considered last questions I sometimes absently put to sources, I fully expected Cocca to laugh off my pessimism when I asked what there was to say there wouldn’t be, at some point in the future, another backlash? “Nothing,” she responded flatly. “Certain people have to prove themselves over and over.” Oh.

***

Supergirl may be one of the weakest superhero movies around, but it still has one of my favourite scenes of any superhero movie ever. It’s a moment around 15 minutes in that was absent from the release I saw as a kid. In it, Supergirl has just landed on earth. After zapping open a daisy with her eyes (just go with it), she discovers that smelling that same flower sends her floating above the ground. Delighted, she wiggles her red-bootied feet and squeals as she stretches her arms wide and her chest out and floats from rock to rock, before gliding for a long spell through the trees. Slater was on wires to shoot this scene, which only really allowed her to move her arms, but several months of practice results in an entrancing “flying ballet” that has her gently swooping upside down and around, her primary colours popping against the comparatively drab landscape and Seventies music. As opposed to contemporary superhero films where everything is amped to the extreme, Supergirl’s juxtaposition against this prosaic backdrop makes her movements, her figure all the more magical.

It’s unfortunate that when TriStar pushed to make Supergirl shorter, according to Ilya, this is what was cut. It’s unfortunate that what remains is Supergirl predominantly using her powers in the context of conflict, rather than in stolen moments of peaceful solitude like this. Because at a certain point you have to question the very idea of the superhero at all. The idea of the exceptional individual, whose superiority manifests in their power to combat and to destroy. Even Supergirl herself finds it unfortunate. “It would be great for me, selfishly,” Slater says, “if we saw more, in the spirit of feminism—true feminism—just a wider range of women carrying the mantle that are not necessarily vaulted or held up for their ability to conquer.”

She’ll have to look beyond Wonder Woman 1984. The sequel to Wonder Woman is about the greed that led us to where we are today, sure, but it is also made within an industry that is itself a symptom of that greed. Diana returns in Reagan times to face a Trump-type (Pedro Pascal) against a backdrop that is now a trope of retro pop culture: the Eighties mall. The film’s release was originally pushed to October 2 in the midst of the pandemic, which you could argue is because it looks better on the big screen. But, again, it’s really about the numbers. It’s more lucrative to have a theatrical release than a direct VOD release, as together they allow a costly film like Wonder Woman 1984 (budget: $175 million) to profit. Which may be why, pushed again to December 25, in a climate that is seeing very few people in theatres, the film will still premiere simultaneously on screen and streaming on HBO Max (a move which was reportedly made to bolster the fledgling service, though international markets without HBO are restricted to a theatrical release only, from December 16 on). Regardless, with the industry’s iron-clad hold on superhero product, I haven’t been able to see the film. Even Vogue, which featured Gadot on its May cover, was only shown half an hour at the Warner Bros. lot (for all of that, Vogue’s verdict—“it is an all-encompassing and visually stunning (and quite loud) experience”—tells us nothing).

In an interview with Collider in December, Jenkins took pity on her public and revealed that the Orwellian date of the title doesn’t just serve as a setting for Wonder Woman 1984, but as a metaphor for today, in which our excesses have virtually sunk us. “I was like, What does Wonder Woman—if Wonder Woman is half God and is wise and kind and loving and generous in this way—what would she say about our world right now? How would she encounter that?” From what I can tell, she encounters it much as she has encountered everything else, with a lot of kicking, lassoing, yelling, and bullet-dodging, leaving plenty of destruction in her wake. But perhaps that’s the big joke. That the tagline, “a new era of wonder,” for a film set in the past, in the end reminds us that we are doomed to repeat ourselves.