In the early aughts, Frank Warren ran a medical document delivery business in Germantown, Maryland. It was a monotonous job, involving daily trips to government offices to copy thousands of pages of journal articles for pharmaceutical companies, law firms, and non-profits. By his early forties, he had a house in a nice subdivision, a wife, a young daughter, and a dog. His family fostered children for a few weeks or months, and he felt a sense of purpose in helping kids who were suffering acute crises in their own homes. From the outside, things appeared to be going better than well. But inside, something was missing: A sense of adventure, or at least a little fun. An outlet to explore the weirder, darker, and more imaginative parts of his interior world. He’d never been one for small talk, preferring instead to launch into deep discussions, even with people he barely knew. He wondered if he could create a place like that outside of everyday conversation, a place full of awe, anguish, and urgency.

In the fall of 2004, Frank came up with an idea for a project. After he finished delivering documents for the day, he’d drive through the darkened streets of Washington, D.C., with stacks of self-addressed postcards—three thousand in total. At metro stops, he’d approach strangers. “Hi,” he’d say. “I’m Frank. And I collect secrets.” Some people shrugged him off, or told him they didn’t have any secrets. Surely, Frank thought, those people had the best ones. Others were amused, or intrigued. They took cards and, following instructions he’d left next to the address, decorated them, wrote down secrets they’d never told anyone before, and mailed them back to Frank. All the secrets were anonymous.

Initially, Frank received about one hundred postcards back. They told stories of infidelity, longing, abuse. Some were erotic. Some were funny. He displayed them at a local art exhibition and included an anonymous secret of his own. After the exhibition ended, though, the postcards kept coming. By 2024, Frank would have more than a million.

*

After his exhibit closed, the postcards took over Frank’s life. Hundreds poured into his mailbox, week after week. He decided to create a website, PostSecret, where every Sunday he uploaded images of postcards he’d received in the mail.

The website is a simple, ad-free blog with a black background, the 4x6 rectangular confessions emerging from the darkness like faces illuminated around a campfire. Frank is careful to keep himself out of the project—he thinks of the anonymous postcard writers as the project’s authors—so there’s no commentary. Yet curation is what makes PostSecret art. There’s a dream logic to the postcards’ sequence, like walking through a surrealist painting, from light to dark to absurd to profound.

I’m afraid that one day, we’ll find out TOMS are made by a bunch of slave kids!

I am a man. After an injury my hormones got screwed up and my breasts started to grow. I can’t tell anyone this but: I really like having tits.

I’m in love with a murderer… but I’ve never felt safer in anyone else’s arms.

I cannot relax in my bathtub because I have an irrational fear that it’s going to fall through the floor.

Even if you don’t see him on the website, Frank is always present: selecting postcards, placing them in conversation with one another. Off-screen, he’s a lanky, youthful 60-year-old emanating the healthy glow of those who live near the beach. Last August, we met at his house in Laguna Niguel, in a trim suburban neighbourhood a few miles from the ocean; when I asked about his week, he told me his Oura Ring said he’d slept well the night before. He offered me a seat on his back patio, and the din of children playing sports rang out from a park below. His right arm was in a sling. He’d fractured his scapula after a wave slammed him to the sand while he was bodysurfing.

As we spoke, I gathered that his outlook on most everything is positive—disarmingly so. The first time he had a scapula fracture, after a bike accident a few years ago, “I had this sense of release, I would say, from my everyday concerns and burdens,” he said. Physically exhausting himself through endurance exercise is his relief from the postcards, which skew emotionally dark. “I’ve had to become the kind of person that can do this every day,” he told me.

For years, Frank has been interested in postcards as a medium of narrative. Before PostSecret, he had a project he called “The Reluctant Oracle,” in which he placed postcards with messages like Your question is a misunderstood answer into empty bottles and deposited them in a lake near his house. (A Washington Post article from the time said “The form is cliche: a message in a bottle,” but called the messages themselves “creepy and alluring.”)

What he considers his earliest postcard project, though, dates from his childhood. When he was in fifth grade, just as he was about to board the bus to camp in the mountains near Los Angeles, his mother handed him three postcards. She told him to write down any interesting experiences he had and mail the cards back home.

Frank took the cards. “It’s a Christian sleep-away camp, so of course a lot of crazy stuff happened, and of course I didn’t write my mom about any of it,” he said. But just before camp ended, he remembered the postcards, jotted something down, and mailed them. When he saw them in the mailbox a few days later, he wondered, Am I the same person that wrote this message days ago? The self, he had observed as a grade schooler, was always in a state of flux.

Examining secrets was part of a lifelong inquiry into what it means to speak. Frank’s parents split up when he was twelve—a shocking and destabilizing event that would define his adolescence. Soon after, he moved with his mother and brother from Southern California to Springfield, Illinois. Messed up by his parents’ divorce and his cross-country move, Frank became anxious and depressed.

While he was in high school, Frank went to a Pentecostal church three or four times a week, searching for a sense of connection with others. At the end of every service, churchgoers would pray at the altar to receive the Holy Spirit. Then, they spoke in tongues. All around him, the Spirit took hold, and people flailed their arms, wept, and danced. Frank looked on with envy and shame. No matter how hard he tried, no matter how many people tried to help him, he never spoke in tongues. It was a spiritual failure, this failure of language.

After college, while living in Virginia, he met a guy named Dave on the basketball court. They became close fast. Dave was funny and sensitive, and also athletic: he and Frank played hundreds of pickup games together. But Dave seemed to be struggling. He was living with his parents, couldn’t land a job. He spent a lot of time on computers, and confided in Frank that he was being bullied online. “You’ve got to get out of here,” Frank told him. That was one of the last things he ever said to Dave. Frank moved to Maryland, and not long after, he got a call from Dave’s father. Dave had killed himself. Frank was crushed. He felt like he should have seen more warning signs, and at the same time, felt helpless. He ruminated on how Dave might have interpreted their final conversation. Out of his parents’ house, he’d meant. Not out of this life.

In the wake of his loss, Frank wanted “to do something useful with his grief,” so he decided to volunteer on a suicide prevention hotline. In training, his supervisors modelled how to inflect his voice to sound non-judgmental, how to ask open-ended questions and get below the surface of everyday conversation—lessons he would carry into his later life. He felt catharsis in listening to other people’s pain, and, in turn, sensed that they appreciated his presence. Simply by talking about their struggles, he found, they sometimes gained new understanding. Once every week or two, Frank listened for six hours, up until late in the quiet of his house, as people unravelled. He let them talk, and he let them stay silent. Listening to people’s confessions in the wee hours of the morning, Frank realized that people needed a way to talk about the messy topics often off limits in everyday conversation.

PostSecret contains echoes of his time volunteering on the suicide prevention hotline. Like the hotline, the project draws attention to the ways people conceal parts of themselves, and encourages disclosure. But the postcards go even further: They’re public, available for anyone to see. They show us the types of stories people normally keep guarded, creating, in the aggregate, a living inventory of our taboos.

*

What is a secret? Knowledge kept hidden from others, etymologically linked to the words seduction and excrement. To entice someone to look closer; to force them to look away.

Secrecy, writes psychologist Michael Slepian in his 2022 book, The Secret Lives of Secrets, is not an act, but an intention — “I intend,” he writes, “for people not to learn this thing.” “To intend to keep a secret,” he continues, “you need to have a mind capable of reasoning with other minds.” Thus, psychologists believe we start to develop a concept of secrets at around the age of three years old, when we also begin to understand that other people have minds—beliefs, desires, emotions—different from our own. At that point, researchers believe, we also develop the ability to experience self-conscious emotions like guilt, shame, and embarrassment. As our theory of the mind develops, we begin to worry that other people are unable or unwilling to understand us, which, in turn, motivates secrecy. Our teenage years are especially ripe for secret-keeping. As we develop stronger senses of self, we distance ourselves from our parents in a bid to assert control over our lives. Keeping secrets from our parents “allows an escape from [their] criticism, punishment, and anger,” Slepian writes, “but it also precludes the possibility of receiving help when it’s most needed.”

Cultural taboos create secrecy. Systems and structures uphold it. The nature, and content, of secret-keeping varies across cultures, but we have always hidden things from one another. The Greek gods had secret affairs; for centuries, women in central China wrote to each other in a secret language to evade the ire of oppressive husbands. Today, people keep secrets for safety: They conceal medical conditions to receive better insurance coverage, and hide their legal status so they don’t get deported. Even scripture has something to say about secrets, which is, mostly: don’t keep them. Proverbs 28:13 reads, “He who conceals his sins does not prosper, but whoever confesses them and renounces them finds mercy.” God, in other words, wants full disclosure.

We keep secrets because we are ashamed or afraid; we tell them because we want an escape. We want to feel accepted, seen. Naturally, we share some secrets with our friends and partners, but sometimes those relationships are the source of a secret, so instead we seek out neutral interlocutors. A bartender in Las Vegas told me the same client came, week after week, to talk specifically with him about her anxiety and troubled dating life. A hairdresser in Salt Lake City told me that Mormons grappling with their faltering faith came to her, an ex-Mormon, to work through family conflict. A therapist I met in Arkansas observed that many of her clients were leaving Christianity and using therapy as their new religion, which she found “a little spooky.”

When I asked what she meant, she told me that people, ex-Christian or otherwise, often look to therapy to find a source of meaning and release in their life—to fill a spiritual and emotional vacuum. Evangelicalism, she said, values “inappropriate vulnerability,” where people share testimonies and break boundaries in public venues. She’s wary when she hears those same stories within the context of therapy—when clients come in and feel obligated to spill everything up front, then ask for cures to their emotional ailments.

Later, thinking about secrets, I remembered this conversation and the phrase “inappropriate vulnerability.” How much vulnerability with strangers is appropriate? How much is too much?

*

For a while, PostSecret was my secret. The website existed in the internet nest I made for myself during adolescence, along with sites like fmylife.com, where users each posted a few lines about the tediums and mishaps of their days, often involving anxiety, depression, alcohol, and sex. They were websites that revealed glimpses of how other people lived, where I could gather anecdotes about adult life and begin to construct an idea of how my own world might look one day.

I grew up in Temecula, a California suburb not too far from where Frank currently lives. My friends and I wandered around the mall to try on skinny jeans, and sprinted around after dark to toilet-paper our classmates’ yards. Suburban life often felt stifling, so I had a habit of inventing stories to make my world seem more interesting. I recounted to friends, with narrative flourish, an encounter I’d had with a freshwater shark in an alpine lake. I created a mysterious, dark-haired boyfriend who I’d met at a soccer tournament. I’d never actually had a boyfriend.

Temecula had a distinctly conservative atmosphere, and it was impossible to escape the shame that accompanied any stray thought about boys, or my changing body. Ours was a town where, in 2008, neighbours supported a California ban on gay marriage. Residents protested the city’s first mosque with signs reading “no to sharia law” in 2010. Arsonists set fire to a local abortion clinic in 2017, and, just in the past two years, the school board would ban critical race theory and reject an elementary school curriculum that referenced Harvey Milk. My family went to a Methodist church, but I sometimes went to Mormon dances with friends; at one such dance in middle school, my dress was too short, so a chaperone made me staple cloth to the hem to cover my knees. During slow dances, we held on to boys’ shoulders from an arm’s length away.

Most everyone I knew in Temecula went to church on Sundays. But I found church boring. I’d excuse myself to go to the bathroom and linger there during sermons, counting the flowers on the wallpaper. I didn’t understand how God, who I didn’t see or hear, could exist.

But even if I didn’t believe God was real, my family did, and religious ideas subtly permeated our home life, shaping what we did and did not talk about. We talked about doing well in school and sports; we didn’t talk about our feelings, or puberty, or dating. My body was a secret, softening and bleeding, fascinating and repulsive.

I didn’t really speak to anyone about these changes, though I do remember one car ride to school with a friend. Her mom was driving, and my friend slipped me pieces of paper in the backseat. In her scrunched-up handwriting, she asked: Do you wear bras? Do you have hair down there? When I was a freshman, my period bled through my capris, and upperclassmen stared as I waddled across campus to the cross-country teacher’s classroom for gym shorts, sweat slicking down my back. I’d only ever used thin pads, and I was too anxious to ask about buying tampons. I didn’t want to talk about it, and no one ever asked.

I can barely remember sex ed programming in school; for years, I thought just sleeping next to a boy could get me pregnant. When, in high school, I started the drug Accutane to tame my unruly face, my dermatologist listed off options for pregnancy prevention to avoid harm to an unborn fetus. A family member who was in the room interjected: “She’ll choose abstinence.” It was only after I left and my world opened up that I understood where I came from. That my hometown, and even my own family, bred secrecy.

If I wanted answers to questions—Should I be shaving? Why do I sometimes feel sad?—I had to find them elsewhere. So I swivelled for hours on an office chair in front of a wheezing PC. It was here I learned of Frank’s work.

I remember the glow of the monitor in the dark upstairs hallway, the feeling of the mouse under my hand as I scrolled through secrets. I remember the padding of feet on stairs, the quick click of the X. Browser window vanished.

*

Over the years, Frank has developed a process for selecting secrets. He sorts the most promising ones into a few boxes. A good secret involves a particular alchemy of art and content. He likes secrets he’s never heard before—there are fewer and fewer these days, but every once in a while something new will pop up—and secrets he has seen but which are presented in a surprising way. At this point, twenty years after the project began, he mostly relies on intuition to select those he posts to the website. He’s kept every postcard over the years, even during a cross-country move. (The secrets he’s posted in the past decade are stored in his upstairs closet and garage; the rest are mostly on loan to the Museum of Us, in San Diego.) Every postcard, that is, except one. He blames a relative for losing it.

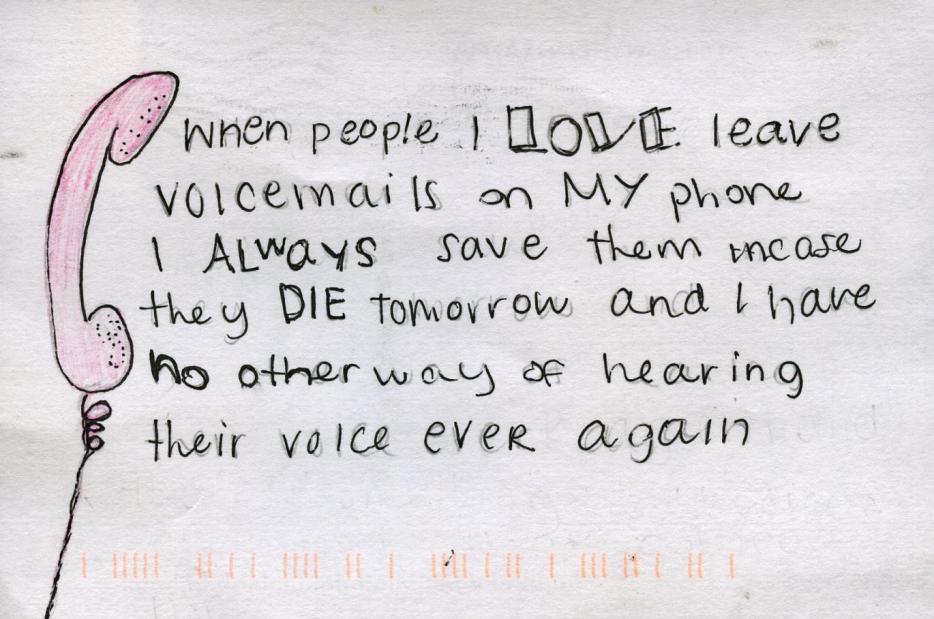

On the website, the scrolling experience is simple enough—scroll, rectangle, scroll, next rectangle—but within the rectangles, something else is happening: a cacophony of colour, scrawl, scribble, cross-outs, stickers, stamps, maps, photographs, sketches. Once, I saw locks of hair taped to a postcard; the writer said they collected the hair of children they babysat. The spectre of tactility, if not tactility itself, reminds the viewer that there are thousands of people behind these postcards, and thousands of hours over the course of twenty years were spent creating them.

Is this sociology? Psychology? Voyeurism? The postcards are shaped like little windows, glimpses into someone’s life, devoid of context. Frank likes to think of them, in the collective, as a cross-section of human nature, and each week he tries to select a range of moods, including a smattering of lighthearted secrets to round out his postcard representation of the psyche, even though most of what he receives is dark. I wondered if reading all these secrets gave him some sort of unique lens into who we are, but he’s not sure. Everyone has different parts of themselves or their lives that they’re afraid to acknowledge. Today, most secrets he receives are about relationships—either feeling dissatisfied with a partner or revolving around loneliness.

“My hope is when people read the secrets each week they have no idea what I think about religion, politics, or feminism. I want to be across the board, so anyone can see themselves in a secret,” he said. “If it’s strong and offensive, guess what, people keep offensive, racist secrets in their heart. That’s part of the project—exposing that.” He doesn’t intentionally seek out racist or sexist secrets, and doesn’t post anything that’s “hardcore racist,” but he thinks there’s value in representing the less-than-savoury aspects of human nature, because that’s a true representation of who we are as a whole.

That said, there are some kinds of secrets he generally doesn’t post. He often doesn’t upload postcards written from the throes of suicidal ideation. He doesn’t want the website to become a toxic cesspool of hopelessness. He also doesn’t generally post the photos included with secrets when doing so might share with someone intimate knowledge that they didn’t know themselves. One postcard, for example, included a family photograph alongside a secret reading, My brother doesn’t realize his father isn’t the same as our father. All the faces were visible. What if the brother saw it and recognized himself? “I don’t feel like I have ownership of that secret,” Frank said. Instead, he posted the text.

There’s no way to fact-check the secrets; Frank takes those sharing them at their word. In 2013, he posted a secret depicting an image from Google Maps and a red arrow. It read: I said she dumped me, but really, I dumped her (body). After an internet uproar, Reddit users found that the location was in Chicago, someone called the police, and the police found nothing, eventually determining the secret was a hoax. Legally, Frank told me, the postcards are considered hearsay.

*

The secrets come without context, so Frank put me in touch with a handful of their authors so I could understand what inspired them to send him their postcards. (Occasionally, the authors email him and reveal their identities.) One of them, Casey, was possessed by secrets for all of her childhood. (Casey is a pseudonym; some people in this piece asked that their names be changed to maintain their privacy.) Her father discouraged his kids from making friends and conditioned in them a suspicion of other people. Because he didn’t work, and because her mother, who she suspected had undiagnosed schizophrenia, was shuttered inside all day, Casey was forced to support the family financially. At age fourteen, she was collecting soda bottles for money. The roof was falling in. She was afraid to tell her family she was gay.

When she left home for college in the early 2000s, she was finally able to make friends of her own accord. All of them knew about PostSecret—it was, at the time, in its heyday—and they’d scroll through the entries every Sunday to compare favourites.

Casey liked the honesty of PostSecret, how it gave voice to the unspoken. Her father still had a psychic hold over her life, but she started opening up about her family to her new friends. One of them, Ramón, was gay, too, and not out to his family. They soon became close. He was an aspiring actor, extroverted and funny. It seemed like he knew everyone, and in turn, everyone said he was their best friend. Casey and Ramón were the only people in their friend group who didn’t drink. They’d both grown up with unstable families and were afraid that alcohol would make them lose control.

But when, in junior year, she started experimenting with drinking, he cut off their friendship, accusing her of betraying her values. She was baffled and frustrated; she thought his response was extreme. To do something with her frustration, she submitted a secret decorated with a photo of him in a Halloween costume reading: A real friend would have stayed around and helped me. She heard he’d seen the postcard and was furious, but they never really talked about it, and today, decades later, they’re no longer close. Casey doesn’t keep secrets anymore. She doesn’t tolerate them.

Some secret-keepers described their postcard as liberating. One woman, V., sent in a secret acknowledging that her infertility was a relief because she wouldn’t have to go off her bipolar medications while pregnant. She wanted to become a mother, but she felt that, even if fertile, her body wasn’t capable of carrying a baby, and she didn’t know how to tell her husband. When she wrote her secret, she stared at it on her table, and when it was posted, she stared at it on her screen. She was struck by the fact she could reveal her secret to the public but not to her partner, and decided to tell him how she felt. Last September, they adopted a son.

Others didn’t seem to think much about their secrets after the fact, I learned when I talked to Carl, aged sixty-seven, a former federal law enforcement agent who lives in Washington State. His postcard depicted a hand of eight playing cards. With a Sharpie, he’d written in all caps: GAMBLING DESTROYED MY 4TH AND LAST MARRIAGE.

As we talked, he was to the point, answering questions in a sentence or two and never elaborating. I could picture him: a gruff, single, middle-aged man who left the house every once in a while to get a cup of coffee with a buddy. He must be lonely, though he’d never admit it, and gambling must have distracted him from his loneliness. “I don’t have any secrets,” he said. “And if I did, I wouldn’t be telling you.”

In 2007, he found a postcard among the “boxes and boxes of crap” in his dead mother’s house. At the time, the divorce from his fourth wife was fresh and he was feeling bitter, so he grabbed a Sharpie, scrawled his message, and put it in the mailbox. “That was that. I was blowing off steam,” he said. “It wasn’t some contemplative therapeutic thing.” Then, he told me something that upended my assumptions about him. “It wasn’t my gambling,” he said. “It was her gambling.”

Some postcards are impulsive, I realized. And because the postcard hadn’t specified whose gambling was the issue, I’d filled in the gap. Fascinated by my own mental jump, I asked more questions. How long had they been married? How did he learn about the gambling? Four marriages? What about the other three? To that last question, Carl said, “I don’t think that applies.”

I wanted to tell him: Of course it applies! I felt like his whole life was bound up in that postcard. Something led to the breakup with his first wife, and his second, and his third, which then led him to his fourth, and to their breakup, and to this piece of mail that ended up on Frank’s website. I wanted his autobiography. I wanted to know everything.

*

Frank told me, “Most of our lives are secret. I think that in the same way that dark matter makes up ninety percent of the universe—this matter that we cannot see or touch or have any evidence of except for its effect on gravity—our lives are like that too. The majority of what we are and who we are is kept private inside. It might express itself in our behaviours, and our fears, and even in human conflict and celebration, but always in this sublimated way.”

Carl was less philosophical. “This thing happened, I forgot about it, and now I’m talking to you.”

*

In the years after he created the website, Frank wrote several books and held live events, which were often sold-out with more than a thousand people in the audience. The events were usually scripted: Frank shared secrets he’d received and secrets of his own. He was no longer the invisible curator. He was, instead, the very reason people gathered. Today he doesn’t do many events, and he says he’s finished writing books. But at the height of PostSecret a decade ago, the events were central to his work—and underscore how much he values the catharsis that follows disclosure.

In 2013, Frank travelled to Australia for a PostSecret tour. At an event in Melbourne, he seemed comfortable assuming his central role; midway through the evening, he shared his own story. He played a voicemail from his mother, who’d seen a copy of Frank’s first book. “I’m not too happy with it, so forget about mailing me one,” she said. This, Frank told the audience, was not a surprise. “My mom has been like that as long as I’ve known her.” His brother and father were estranged from her, but he and his mother still had a functional relationship. “Even so, my earliest memories being around my mom are memories of having to have my defences up. I couldn’t let my guard down. My earliest memories keeping secrets were from my mom,” he said.

He told the audience about his experience with the Pentecostal church. At the end of every service, he explained, members would share their testimonies, and the congregation would cheer and shout, “Amen!”

Evoking that part of the service, Frank said he wanted to share his own testimony with the audience: If he could go back in time and erase all the moments in his life that had caused him pain and humiliation and suffering, he wouldn’t. Each one of those moments, he said, had brought him to this moment and to the person he is today. He likes who he is today. Suffering in silence led him to make PostSecret; the darkest parts of his past were inseparable from the parts of himself he liked now, and they made him a better father. If you can get through your own struggles, he told the audience, “you’ll have this beautiful story of healing, a story that you can share with others, others who are in that struggle.” Adopting a faint Southern accent, he asked, “Can I get a witness? Can I get an amen, brother?” Someone shouted amen. “Thank you, sister.” The theatre erupted into applause.

Then, Frank invited people to line up in the aisles and share their secrets. When one woman stepped up to the microphone, she said, “About a year ago, my ex-boyfriend raped me.” Her voice broke, and through tears, she continued, “And then told me he was getting engaged the next day. I think it’s about time I ask for help.” The audience applauded, and Frank commented that often the first step to making change in one’s life is sharing a secret. The woman left the microphone. The next person stepped up to share.

There was something both beautiful and garish about this spectacle. I remembered my conversation with the Arkansas therapist and the idea of inappropriate vulnerability. Watching the woman speak, I felt a mix of queasiness and regret and rubbernecking and curiosity. It was the feeling I have when I reveal too much about myself too quickly, without the slow buildup of trust and intimacy. Then the microphone went to another person, as if this were a conveyor belt of secrets, and there was no time to grapple with the weight of what had just been said.

In a 2016 LitHub essay, the writer Erik Anderson accused Frank of profiting, however indirectly, from other people’s traumas with his books and speaker fees. Frank often refers to secrets as the currency of intimacy—we exchange our secrets and become deeper friends or partners—but to Anderson, they’re also Frank’s professional currency, the reason he has a career at all. What happens to the secrets of PostSecret, he asks? Does having a secret posted actually do anything beneficial for the sharer? “Warren’s feel good message about the healing benefits of disclosure, about self-actualization through confession, may elide a painful truth about secrets,” he writes. “Once shared, especially anonymously, they become secrets again, hidden by and in the very excesses of the internet that made them possible.”

Frank told me he’s aware of the delicate role he plays as the keeper of people’s secrets. People trust him to treat their stories with care, so he’s never tried to monetize the website. It’s true, he says, that most of his income from the past decade has come from book advances and speaker fees. But, he told me, “I don’t get too much negative feedback from anyone in the community.” And as for what happens to the secrets, he says he hopes that by sharing them, people might be motivated to take action. Or perhaps, like on the suicide hotline, they can begin to see their secrets differently. We often assign secrets a physical weight; maybe by making them public, we can make them lighter, or smaller. But none of that is guaranteed.

For an hour, the theatre in Melbourne was transformed into a church of secrets. In the church of secrets, pain is pedagogy. Pain must teach us something, must have meaning, or else how could we live through it? We turn pain into a story, and make that story public in the hopes that we might get something in return. Empathy. Action. Friendship. Money. If I could go back, I would never choose pain.

*

I have a secret—this is the language we use. We possess secrets, hold them close, though sometimes, perhaps, it’s better said that secrets possess us. And by secrets I mean the things we feel we cannot say, and so no one says them. What I mean by secret is taboo. What I mean by secret is fear.

Around a year ago, when I was in California for the holidays, a high school friend who I’ll call Sam invited me to meet in a park. Another friend, Alex, was in town too. I hadn’t seen either of them in years. We sat underneath a cypress tree and threw a rubber Frisbee to the Australian shepherd Sam was dog-sitting. The air smelled of salt. The grass itched our legs. Sam told us she’d been going to sex therapy with her husband, who she married when she was twenty-three. She was now twenty-seven. She and her husband were both deconstructing from the church, a painful personal reckoning with a culture that preached sexual purity. She’d always felt guilty about sex, and she didn’t know about pleasure.

“I didn’t start going to the gynecologist until after college,” I offered in commiseration. “Until tenth grade I thought having sex was just sleeping next to each other.”

“I always felt so observed,” said Alex, the first of us to have a boyfriend in high school.

“You were observed,” I said. We laughed, and I sat back and marvelled. The three of us had slept together on blow-up mattresses and swum at the beach and splashed in backyard pools but had never really talked—at least, not about the things we considered secrets. We were women now. All these years later, we’d finally found the words.

I wondered if Frank had ever been able to talk openly with his family. PostSecret was, after all, partly inspired by the difficulties of his upbringing. Frank told me his father was initially skeptical of the project, finding it voyeuristic, and maybe unnecessary. But eventually he began to appreciate the project and even told Frank something he’d been holding in for a while.

But Frank’s mother never came around. When we were sitting on his patio in Laguna Niguel, I asked about her a few times, and he told me a story. When he was a teenager, after he’d moved to Illinois, Frank got into a fight with her. He can’t remember what happened, only that he’d probably done something to anger her. He ran to his room and locked the door. His mom pounded on the door with a mop, broke through one of the panels, and reached her hand through to unlock the door. Frank ran into his bathroom and opened the window. It was snowing and dark outside, around 9 p.m. He climbed through the window and ran a block down the street to his friend’s house. He and his friend started talking as though this were a normal hangout, but eventually, his friend looked down at his feet. “Where are your shoes?” Frank was wearing only socks.

I asked another question. Gently, without drawing attention to what he was doing, Frank changed the subject. It was the first time I’d seen him withhold information. He didn’t want to talk about his mother anymore, and I didn’t need to know.