"Don’t bother me, I’m meditating!”

Growing up, I knew that if Mom was lying upside down, I was not to disturb her. She would strap her feet under a belt at the top of a black vinyl reclining board and lie back at a forty-five-degree slant. This was her version of meditating.

Mom first dipped her toes into spiritual waters in the early '80s, after I was born. While working on her master’s of education, she signed up for a Transcendental Meditation class. She would leave the house with fruit and flowers (offerings for some deity) and come home with a secret mantra. Mom said she became interested in meditation because her fight-or-flight signals were constantly spiking. “I was always on the defensive. I needed to slow down,” she told me. But she was soon turned off by TM’s hierarchical structure, so she moved on to Zen meditation—and then found it too restrictive. “They made me sit cross-legged on the floor!” she complained. Mom eventually settled on Vipassanā, which is all about seeing things as they really are: “I took to it like an anxious duck to clear water.”

She was also into Iyengar yoga when I was little. Mom was always folding herself into various poses around the house—doing a more comfortable version of downward dog, for example, where she’d bend forward and rest her outstretched hands on the kitchen table. Or she’d drop down on the living room carpet and kick her legs up into a shoulder stand. There are baby pictures of me climbing up on her, mid-pose, as if she were a human jungle gym.

Mom’s proclivity for meditation and yoga was considered odd back then. We lived in the mostly Jewish, upper-middle-class Cedarvale neighbourhood, where head-to-toe Lululemon and an over-the-shoulder yoga mat were still decades away from becoming de rigueur. Mom was a teacher. We lived in a nice house with a pool. We certainly passed as normal. But I always had a feeling that Mom wasn’t like other moms.

Case in point: I remember in senior kindergarten coming home and announcing that I needed a Halloween costume for school the next day. After a few minutes of scrounging, Mom’s face lit up with an idea. “You’ll be garbage!” she proclaimed. She got a black garbage bag from under the kitchen sink, threw it over my five-year-old body, and used her hands to tear holes for my arms and head. It was her next move that was really inspired, though. She started fishing through the actual garbage bin for dry pieces of authentic trash that we then threaded together with string before festooning me from top to bottom. As a Jewish kid, it was as close as I ever got to trimming a Christmas tree.

The next day, I couldn’t have been more embarrassed, surrounded by My Little Ponies, He-Men, witches, and ghosts. How on earth did Mom think this was a good idea? There I was, with an empty box of our dog’s Milk-Bones dangling around my neck. My teacher, Mrs. Winemaker, looked me up and down before making a concerted decision to declare—a little too enthusiastically—that next year she wanted to be garbage for Halloween. Goddess bless.

Mom was very caring and loving in her own inimitable way, but she wasn’t much of a capital M Mommy. As a joke, she would sometimes refer to herself as “Mommy” when she’d catch herself performing something quintessentially motherly. But it was always said in self-reflexive jest. She didn’t bake cookies. She didn’t brush my hair. She didn’t put sweet notes in my lunch box. In fact, Mom never even packed my lunches. I distinctly remember when she said to me, “You’re in senior kindergarten now. It’s time you made your own lunch.” We were standing in front of the fridge. I looked up at the towering shelves of food with utter confusion.

“What should I bring?” I asked.

“Your cousin Sarah brings a yogurt,” Mom replied.

For much of elementary school I’d pack a cappuccino yogurt and a box of Smarties; when lunchtime came I’d pour the latter into the former and stir until the dye bled into a colourful swirl. Sometimes I’d bring mini pitas stuffed with Nutella. I usually rounded things off with a Mini Babybel, a Coke, and a Caramilk bar (for dessert). I was very popular in the lunchroom.

But even more than I enjoyed my signature concoction, I loved going to my friend Alimah’s for lunch. Her mom, Barbara, was a stay-at-home mother, so Alimah could go home every day for chicken noodle soup, tuna sandwiches, and sliced-up carrot and celery sticks. Seeing Barbara in action was fascinating. She was more like the moms on TV: aware of Alimah’s school assignments, making sure she did her homework, limiting how much TV she could watch. Their home was an oasis of routine and predictability. Barbara even assigned meals to days of the week. Wednesday was spaghetti night. Friday was pizza.

There wasn’t much cooking going on at our house. Much later Mom would insist she’d been “chained to a stove for eighteen years,” but the rest of us remember differently. For dinner we’d usually go out to restaurants, order in, or Mom would pick something up on her way home from work. Every so often Mom would courageously attempt to concoct something interesting, like Greek fish or chocolate pasta. But it would be more of a performance than a bona fide meal. “Mommy made supper!” she’d sing.

She certainly wasn’t interested in being the type of mother—or wife—who put her own life on the back burner, but she’d also made a conscious decision to not be “too overinvolved.” She’d felt smothered by her mother growing up and was afraid of even coming close with me. Literally. Sometimes she’d look over at me lovingly and pet the top of my head. “Pat, pat,” she’d say, careful to never intrude on my physical space.

Mom had had a list of things she’d do differently when she had a daughter one day. She would never tell me what to do with my hair. She would never make me feel guilty for choosing to do my own thing. Above all, she would never lean on me. “I never want you to feel like you have to take care of me,” she’d say.

Mom believed it was important to teach me things. She explained how her mother always wanted to do everything for her when she was little, which she interpreted as a power play to make her extra dependent. With me, the pendulum swung. Mom wanted me to be independent. Ultra independent. I was often left at home alone, and was the only seven-year-old allowed to walk up to Eglinton—one of Toronto’s major arteries—on my own.

I routinely made that six-block trip to do my errands. I’d go to my favourite candy store, The Wiz, and fill up a large bowl with Pop Rocks, Fun Dip, and Bonkers, and then head across the street to Videoflicks to rent a comedy like Heathers or Ruthless People. On the way home I’d stop off at China House for a bowl of wonton soup. At first the waiters were a little weirded out by a child dining solo, but they soon came to recognize me as a regular—who paid in quarters and dimes from her piggy bank.

When I inquired about Mom’s free-range approach to parenting years later, she happily defended herself. “I taught you how to look both ways and cross the street, and you were very good at it. So I let you go off on your own!”

I was allowed to eat as much Häagen-Dazs, watch as much TV, and stay up as late as I liked (I even had a TV in my room). Mom treated me like a mini adult. When I wasn’t in school, I could do whatever I wanted with my time.

I relished my freedom—I wouldn’t have had it any other way—but there were times when I’d fantasize about having some authority at home. Time to take your medicine, I’d say to myself as I popped my daily Flintstone vitamin, imagining an adult was forcing me. To fit in with the other kids at school, when I’d get grass stains or rips in my pants I’d pretend to be afraid of Mom’s wrath. “Man, my mom’s going to kill me!” I’d say, mimicking what I’d heard on the field. I knew Mom couldn’t care less. (If anything she was proud of me getting rough and dirty.)

I loved Mom so much, but I’d sometimes wish she was more like Barbara. Once when I was sick and she didn’t offer to bring me anything, I admonished her: “When other kids are sick, their moms bring them orange juice!” (“You don’t want one of those other moms,” she’d snap back. “I’m more fun!”)

Mom may not have been like other moms, but the truth was I wasn’t like other daughters. As I grew up, people mistook me for a boy. I was a tomboy—or what Larry David would later call “pre-gay.” I had short moppy hair, wore only jeans and T-shirts, and felt a profound sense of disappointment with the girls’ shoe section. I was pretty happy in general—I had friends and did well at school—but I always had a feeling of being on the outside. I didn’t feel like one of the girls, and I knew I wasn’t really one of the boys. The only other kid who reflected my gender was Casey from Mr. Dressup. And Casey was a puppet.

Once, when I was six, Mom attempted to put me in a dress for shul. I resisted. We struggled. She even tried to sit on me. “Please, Rachel! It’s the High Holidays!” she begged. “I don’t want to!” I yelled back, squirming my way out from beneath her. Back then Mom still cared a little about what people thought and didn’t get that it was actually humiliating for me to wear feminine clothes. Thankfully, she quickly gave up, and I emerged triumphant in ripped jeans and high-tops as we left the house. Staying true to the list of things she would do differently from her mother, it was the last time Mom ever tried to dictate my sartorial choices (or any of my choices for that matter).

When I was seven, I told my parents that I wanted to join the local Forest Hill hockey league. Back then there were only boys in the league, so the organizers were apprehensive. But no one said no.

Even when I got two penalties in one game, Mom was so proud of me for being the only girl in the league. Her little girl being called a “goon”? She couldn’t have been more pleased. She loved it when the other mothers would tell her that their sons were intimidated by me. “Way to knock ’em dead, sweetie!” she’d cheer.

Mom was an out and proud feminist, and she wanted me to be one too. She’d order children’s books from the Toronto Women’s Bookstore featuring strong female characters. (There were only a handful at the time; my favourite was Molly Whuppie, about a clever girl who fearlessly outwits a giant.) I was fully on board with being a baby feminist. I remember Mom teaching me the word “assertive,” although I didn’t need lessons in how to embody it. Mom recalled how, when I was three years old, she tried to scare me into submission. “I’m counting to three!” she warned. “One . . . two . . . three . . .” Apparently I just stood there, unimpressed. “What are you going to do?” I asked. Mom laughed and gave up after that. “I learned I had to go at things slant with you,” she explained yearsl ater. “I couldn’t go head to head. You’d win.”

When I was eight, I decided to switch schools. I was bored at my neighbourhood elementary school. I was already able to multiply in parts and do long division, so grade two math just wasn’t doing it for me. “I’m sick of counting animals!” I complained. One day I went to checkout an alternative school called Cherrywood with Barbara and Alimah, who was considering transferring there. What I saw amazed me. There were no walls, teachers were called by their first names, and students could work at their own grade level. Their system made perfect sense to me. That day I came home having made my decision: “I’ve found a better school and I’m going there,” I declared. Mom was totally supportive. She didn’t want me to feel held back, and besides, she was an alternative school teacher herself.

On PD days Mom would bring me along to City School, where she taught English and drama. There were posters on the walls with slogans like stop racism and being gay is not a crime, bashing is. I’d stare wide-eyed at the older students with their rainbow mohawks, lip piercings, and knee-high Doc Martens. Teenagers didn’t look like that in Cedarvale. They fascinated me. And they all loved my mom, their rebellious role model.

Elaine was an unconventional teacher, even by alternative school standards. She taught a course called “Nature Writing as a Spiritual Path” and got her students to meditate and hug trees. She’d take her writer’s craft class out to cafés to work and encourage them to write freely about whatever was going on in their lives, pushing them to go further than they thought they could go as writers. Mom thought it was important for students to own their education, to be involved, and to have a lot demanded of them. She was incredibly supportive of her students and treated them with more respect than adults usually did. “I wish your mom was my mom,” they’d say to me. I’d roll my eyes, even though deep down I knew how lucky I was.

To Mom’s credit, whenever I seriously asked her to change her behaviour, she listened. Unlike her mother, she wanted to be able to hear us. She stopped reading books during my hockey games after I told her I wanted her to watch; she refrained from gossiping about me to her friends when I asked her not to; and she even started bringing me juice when I got sick. “Mommy brought you orange juice!” she’d sing.

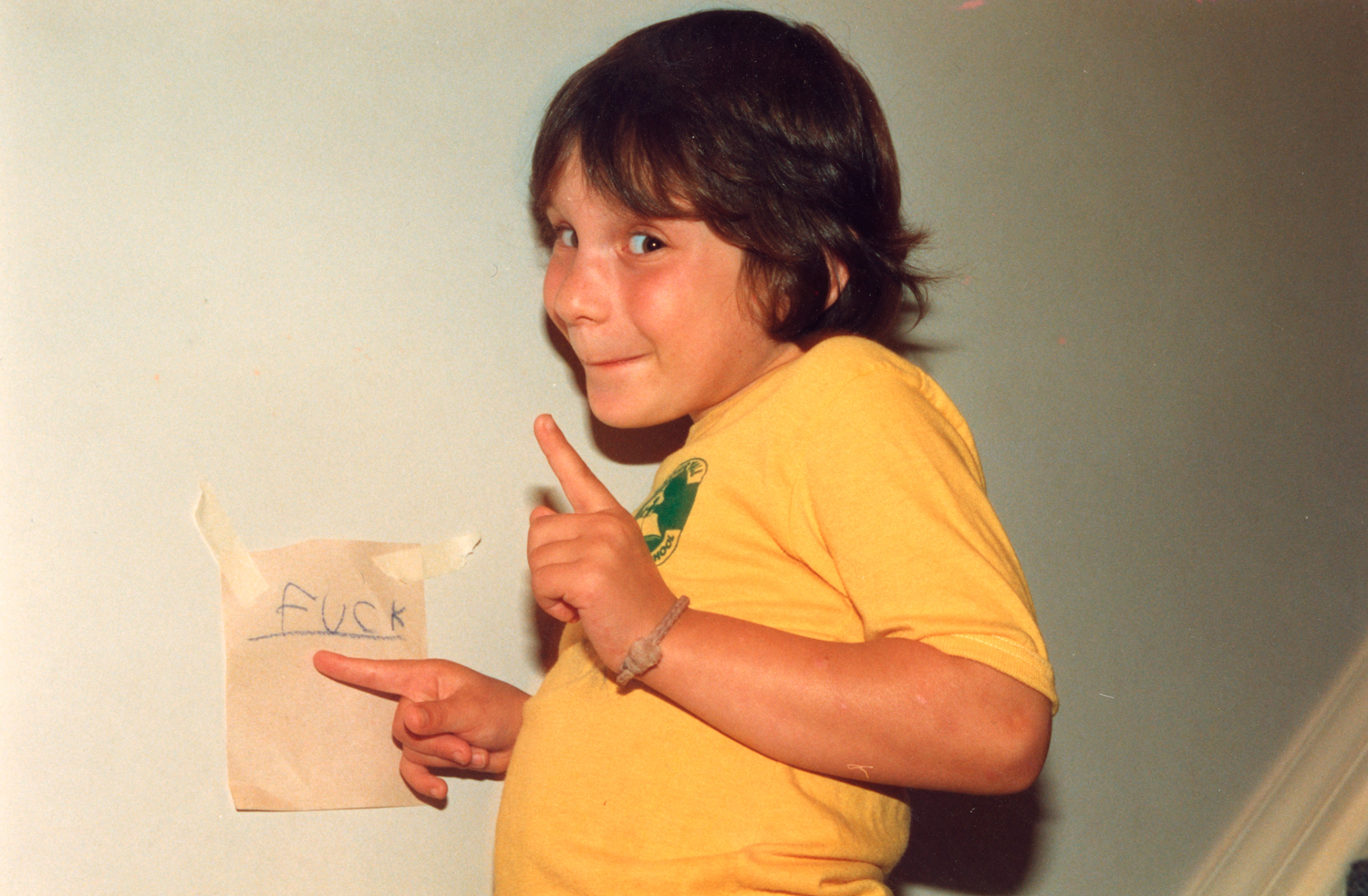

But the learning curve sometimes seemed like a gentle slope. I didn’t always feel heard. When I was really upset with Mom, I had to find creative ways of getting her attention. On one occasion when I was about seven, angry about who knows what, I took a pad of paper and wrote “Fuck” on every single sheet. Then, while Mom was out, I went around the house taping up my expletive art—on the walls and furniture, inside drawers and cupboards. There must have been a hundred sheets. I didn’t want to be cruel—I considerately used masking tape so as not to peel paint off the walls—but I did want to get my message across. She’ll see how mad I am, I thought. She’d open the front door and be greeted with “Fuck.” She’d walk into the hallway and see “Fuck.” She’d open the fridge, “Fuck” again.

I didn’t get the response I was imagining. I sat at the top of the stairs and watched as she stopped in her tracks, gazed around with wide eyes, and burst out laughing. “Get the camera!” Mom shouted. I came downstairs and joined in the laughter, cheekily posing next to my “Fucks.” I was satisfied to at least get her attention. Like goys finding Easter eggs well into May, mom continued to discover my four-letter treasures for weeks. “I found a ‘Fuck’!” Mom yelled out as she opened the china cabinet to get the Shabbat candles.

My parents weren’t religious, but we still lit candles on Friday night and kept kosher in the house. I resented not being allowed to have Lucky Charms—the marshmallows were considered treif. When Mom actually did make rules, they seemed so arbitrary. I can eat all the sugary cereals I want except the one that’s magically delicious?

By the same lazy logic, I was sent to Hebrew school every Sunday: apparently it was “what Jewish kids do.” I hated it. The idea of God was preposterous to me, the stories were way too far-fetched, and I definitely wasn’t into all the male pronouns. Mom would bribe us with a bacon-fuelled pit stop at McDonald’s on the way (she wasn’t one to care for Commandments of any kind).

Mom went along with the kosher thing at home. But when we were out of the house, it was a different story. She’d sometimes buy delicate slices of prosciutto before picking me up from one of my extracurriculars, and on the way home we’d park the car and dangle the mouth-watering strips of meat into our mouths, laughing like criminals.

In an effort to get my parents to allow me to quit Hebrew School, I emerged from my bedroom one Sunday morning having taped crucifixes all over my clothes (I was crafty with the masking tape).

I walked up to Mom and said, “If you don’t let me quit, I’ll marry a Christian!”

“So what?” she said, unfazed.

“Okay, well then I’ll marry a Nazi!” I shouted.

Mom burst out laughing. I’d won her over!

They eventually acquiesced, but not without warning me that I wouldn’t be allowed to have a Bat Mitzvah. That was more than fine by me. I wasn’t interested in selling out for some gold bling with my initials on it. And I certainly wasn’t interested in becoming a woman.

Although Mom exposed me to sophisticated culture—art galleries, museums, libraries, and culinary adventures—my interests veered more toward puzzles, riddles, and logic games. My teachers thought I might even become a mathematician. But if there was one game that defined me, it was chess. (One of the best parts about going to Cherrywood was that playing chess counted as math.) I started competing in tournaments when I was ten, and would regularly spend my weekends in hotel conference rooms playing with nerdy boys. I was consistently ranked fourth in Ontario in my age group.

What I liked most about chess was that chance had nothing to do with it. No need for lucky cards or dice or troll dolls. It was up to me to use everything in my arsenal—logic, calculation, memory, even psychology. Mom would remark on how I never got flustered when I was down. “You don’t give up. You become even more focused,” she’d say with great admiration. I learned to rely on my strategic-thinking skills on and off the board, believing I could think my way out of any problem. In our family, if I argued my case well enough, I could get whatever I wanted. I remember saying to my parents, “If you guys can have coffee in the morning for your caffeine, I can have a Coke.” For some reason, that one worked. “You’re going to make a fine lawyer one day” was a familiar refrain.

Mom spent most of her time at home reading. I can still picture her sitting in the living room by the fireplace, a book in one hand and a pink Nat Sherman Fantasia in the other. She wouldn’t even inhale—the thin, pastel-coloured cigarettes with gold filters were just props in her one-woman performance of “I am a Parisian.” She’d put on one ofher French records—Serge Gainsbourg or Edith Piaf—and escape into her French fantasy world. I can still hear Georges Moustaki singing “Ma Liberté.” She played that one a lot.

***

When I was thirteen, my parents divorced, and Mom moved into a bachelor pad she’d inherited from a fellow divorcé. It had one tiny spare room, which became my room.

When I stayed with Mom, it was just us. She was now living on only her teacher’s salary, but we’d still go out to restaurants in the neighbourhood. At home we did ear-candling treatments for each other and played a card game that featured feminist writers like Louisa May Alcott, Phillis Wheatley, and Emily Dickinson (Gertrude Stein was the wild card). While I’d be focused on collecting sets of four, Mom would tell me about her literary heroines: “Little Women is really the story of Louisa and her family. Louisa was Jo . . .” Often we’d just talk. More than anything else, talking was our thing. To this day there’s no one in the world I’ve ever had an easier time talking to.

What I liked most about Mom’s new place was that we didn’t have to keep kosher. For breakfast I’d often heat up a can of Chunky clam chowder, although most mornings Mom would go out to the corner and bring me back McDonald’s Hotcakes. She’d plop the golden Styrofoam container down on the kitchen table and sing “Mommy made breakfast!”

To most people’s surprise, the divorce wasn’t initially that distressing for me. It only really started to hit me once my parents began dating. Just as I was entering adolescence, the two of them began behaving like full-blown teenagers. Mom fell madly in love with a man who was about to move to Albany to be the director of the New York State Museum. She took a sabbatical to study holistic ways of teaching and began a long-distance relationship with him, regularly leaving town for weeks at a time.

I missed Mom like crazy when she was gone. It was hard being without her. I would often call her crying, pleading with her to come home. She’d listen to me and lovingly calm me down, but she wasn’t about to get in the car and drive back. She explained to me how important it was for her to have a full life of her own. “I’m not just a mother,” she would tell me. “I need passionate love too.”

As gross as it was to hear her say that, I understood that Mom had her own needs. I tried my best to respect her wishes, but there were times when I needed her to be there for me and she wasn’t.

***

It was during those three and a half years while Mom lived part-time in Albany that her journey of self-discovery really took off. The northeastern United States is a hotbed of spiritual retreat centres. Mom began frequenting New Age havens like Kripalu, Omega Center, Zen Mountain Monastery, Insight Meditation Society, and Elat Chayyim, a Jewish renewal retreat in the Catskills. (There, she told me, they’d sit in a circle, with their index fingers touching their thumbs, and chant “Shal-Ommm, Shal-Ommm.”) She often slept in dorm rooms and chopped vegetables alongside college students in exchange for what would otherwise be a thousand-dollar yoga vacation. Mom didn’t need a large income in order to have a large life.

Her retreats gave her time and space to work out her issues. She still had a lot of childhood resentment, even though by then she was getting along well enough with her own mother. She was proud that she’d taught her mother to treat her more respectfully. “It’s important to set boundaries,” Mom told me. Before her father died, he’d apologized to her in his Polish-Jewish accent for having not acknowledged her feelings enough. I know that meant a lot to her. But still, Mom was desperate to free herself from her family patterns. She would write unsent letters to her parents as well as responses from the perspective of her ideal mother or father.

I was happy that Mom was working out her shit, but sometimes I felt like I had to compete with her inner child. My heart would break every time she drove off in her cappuccino-coloured Honda with its one nuclear bomb can ruin your whole day bumper sticker. I spent a lot of time crying on my own, until one day I decided I wouldn’t cry anymore. I’m not sure if it was due to my natural temperament, my gender identity, or my parents not being fully attuned to my emotional world, but I resolved to toughen up and be a little man. Throughout junior high, I kept a busy schedule with sports and chess. I was on all my school’s sports teams, including the boys’ hockey team, and played competitive hockey, soccer, and softball on the side. I was the city’s school chess champion two years running.

It was also in junior high that I experimented with being a girl, albeit only part-time. I was invited to friends’ Bar and Bat Mitzvahs almost every weekend and could no longer get away with wearing pants to shul. When Saturday rolled around, I’d trade in my jeans and T-shirts for pantyhose and a dress. My friend Jane helped me pick out girl party attire at the mall and taught me about shaving my legs. My friend Sarah gave me a nudge when she’d catch me manspreading in a skirt in synagogue. Being a girl didn’t come naturally to me, but I passed well enough. Boys liked me, and I even had crushes on them. Though, looking back, I think my attraction was probably more about me wanting to be one of them (or because at that age they looked like cute little baby dykes, with their short hair and smooth cheeks, like little Justin Biebers).

Mom brought me along with her to Albany a couple of times. On our last trip there she took me hiking in the Adirondacks. We climbed a steep, rocky trail up Crane Mountain, scrambling our way to the summit. We both felt a great sense of accomplishment as we looked out over the forest-covered mountains below. Mom was proud that she’d taken me, at thirteen, hiking up a three-thousand-plus-foot mountain. “When I was thirteen my mother took me discount shopping for our bonding time,” she told me. On the way down we came to a large pristine pond where we decided to take a break, sitting next to each other on a giant boulder in the shade. Mom pulled out a watercolour set along with some paper. Together, both painting quietly, we stared out at the glistening water and tall beech trees in the distance. It was a serene moment we would often look back on fondly.

A couple of days later Mom broke up with her boyfriend. She’d felt increasingly torn between being with him and being with me in Toronto. I vividly remember seeing her break down in tears as we got in the car to drive home. She was always so conscious never to lean on me that she rarely showed any vulnerability around me at all. Years later, Mom would admit that although she’d wanted a great love, she was scared. “I had a strong feeling that if I married him, I would be happy for a year and miserable for the rest of my life.”

When I was fourteen, I decided to live with Mom full-time. By then Mom had moved into the Hemingway. She made a concerted effort to make me feel welcome. This time, she gave me the bigger room.

It was during this period, in the mid-'90s, that Mom’s alternative lifestyle began to rub off on me. I went to yoga classes with her and wore a crystal aromatherapy necklace she’d given me as a gift. She took me on road trips to Buddhist monasteries and silent meditation retreats. In the car, we’d take turns listening to her folk music (Joni Mitchell, Phil Ochs, the Stone Poneys with Linda Ronstadt) and my Ani DiFranco, Tracy Chapman, and Indigo Girls tapes. We visited the Kushi Institute for Macrobiotics in Massachusetts, where we sipped twig tea and learned how to cut a carrot properly (from tip to stem) so as not to kill its life force. My teenage curiosity and idealism latched onto these alternative doctrines. I was drawn to the rules and guidance they provided.

But for Mom, soul searching was more than just a teenage phase. She was always trying out something new. Trance dancing, magnets, meridian tapping, past-life regression therapy, colour therapy, cranial sacral therapy, chakras, crystals, rolfing, reiki—she would embrace each fad with the same enthusiastic yet noncommittal curiosity every time. Her perspective was, Why not try everything? It doesn’t hurt, and it might lead to unexpected wisdom. And hey, if they kept her looking younger, all the better! She regularly did these Tibetan exercises called “The Fountain of Youth,” where she’d spin around with her arms outstretched. (Mom said that when she first saw “spinning” classes pop up in New York City, she mistakenly thought her exercises were taking off.) I saw the marvel in her New Age dalliances, but I definitely took them with a big grain of Himalayan salt.

For Mom, spirituality was like a buffet where she was free to pick and choose what she wanted—she could create her own narrative blend that suited her personality and her needs. It was all about knowing herself better, being able to laugh more about her frailties, and becoming as real as possible. As a feminist, she wanted to own her spirituality without giving herself over to dogmatic ideas or practices.

Mom was a badass Buddhist. Of course, she believed that rules were optional, even the ones the yogis wrote. Her Four Noble Truths were coffee, wine, reading, and talking, or what Buddha might call “contraband.” When she was supposed to be staying silent on her meditation retreats, she’d leave me hushed, long-winded voicemail messages: “Hi darling, I’m not supposedto be talking, but I just wanted to let you know I’m okay. Um, it’s so weird to be speaking. . .” She would smuggle in novels and escape to nearby villages to get The New York Times and a cappuccino. When she did a work exchange at Thich Nhat Hanh’s monastery in the south of France, she led a group of fellow volunteers through the surrounding vineyards on a wine-tasting tour. “I was like the pied piper,” she told me. “They all followed!”

***

On my seventeenth birthday I set out on my own journey of self-discovery. My best friend Syd had lent me her copy of The Teenage Liberation Handbook: How to Quit School and Get a Real Life and Education. Essentially a recipe for teenage anarchy, the book became our bible. The Good News? Rather than being confined to classroom walls, teens could reclaim their natural ability to teach themselves by following their own curiosity and having real-world experiences. I had seen the light! After reading a few more books on “unschooling,” I knew what I had to do.

That January, I finished my last exam of the semester and flew to San Francisco. There, Syd and I hung out with an older anarchist couple we’d met who took us around to protests with their giant papier-mâché puppets. Like Mom, I learned to live large on not much. We couch-surfed at intentional communities in Santa Cruz and Palo Alto and travelled up the west coast of the U.S. on a backpacker bus called the Green Tortoise. We hitchhiked across B.C., working on organic farms in return for accommodation and three wholesome meals a day. As a city kid, it blew my mind to see what broccoli looked like in its natural habitat.

To say that I was self-righteous about my decision would be the understatement of the decade. If anyone ever said I was “dropping out of school,” I’d diligently correct them. “I’m not dropping out,” I’d say. “I’m rising out.”

I’d always gotten good grades, but I didn’t want to learn that way. I wanted to see the world and have adventures. Mom was a little anxious, but she understood where I was coming from. She was ultimately very supportive, even seeing me off at the airport. “You have guts,” she told me.

For the next two and a half years I travelled around the world to hippie hotspots with Syd and some of our other “unschooled” friends. I took silver jewellery–making lessons in Mexico, learned Spanish and taught English in Guatemala, trekked the twenty-day Annapurna Circuit in Nepal, and attended talks by the Dalai Lama at his temple in Dharamsala, India. I was living the teenage dream. I would come home in between my long excursions and stay with Mom just long enough to make the money to go back out again. I worked at a bohemian gift store in Kensington Market that specialized in Ecuadorian sweaters and Circle of Friends pottery.

Sure, I’d quit school. But it wasn’t like I was doing drugs—I was mainlining brown rice and Spirulina Sunrise bars. My form of teenage rebellion was being a hippie fundamentalist. I was a strict vegetarian. I used only “natural” body products. I refused to take any pharmaceuticals (not even Tylenol). I hung out at the health-food store as if it were the mall. My uniform consisted of second-hand jeans with colourful patches, striped Guatemalan shirts, and hiking boots—even in the city. And, if that wasn’t bad enough, the surest sign of my hippie cult status? Dreadlocks. It hurts to admit it, but I had ’em. In my meagre defence, it was the late ‘90s, when they were “in style” (and before I learned about cultural appropriation). I also theorize that my Manic Panic–dyed dreads were an expression of my dormant queerness—a gateway to the short dyke-y haircut I subconsciously knew I was moving toward.

***

One of the biggest perks to ditching high school was that I didn’t have to deal with normal teenage things, like dating. I could totally avoid it. And I did, even if I couldn’t avoid the subject altogether. The first spring after I quit school, Syd and I found ourselves pitching in at a women-only community near Nelson, B.C. This lesbian idyll was on a mountainside, up an old logging road, entirely off the grid. Even their bathtub was wood-fired.

One evening a bunch of short-haired wimmin arrived in their trucks, giddy with excitement. One of them had a VHS tape in her hands that she was cradling like some sort of Holy Grail. Our host let us in on the commotion: they were congregating to watch the “Coming Out” episode of Ellen. It was essentially the lesbian moon landing of 1997.

They all rushed into action. One of them peeled back a macramé tapestry to reveal a hidden TV in the corner of the livingroom. Another got the generator going. Everyone gathered around for the momentous—if pre-recorded—occasion. For one night only, we would plug back into civilization for the sake of Ellen DeGeneres.

I watched as Ellen finally got up the courage to say to Laura Dern’s character “I’m gay,” only to accidentally blurt the words into the airport P.A. system. I laughed out loud, but on the inside I was freaking out. It was the first time I remember seriously thinking, I think that’s what I am. I was a vegetarian who played competitive hockey and softball, who in that moment “happened” to find herself in a room full of lesbian separatists. How many more hints did I need?

***

After many months on the road, bouncing from place to place, the idea of staying put and going to university started to seem appealing—an exciting new adventure in itself. I had some older hippie friends who went to Trent, a lefty liberal arts university just over an hour’s drive from Toronto, and would sometimes visit them there. Their courses in feminist philosophy and alternative media sounded way more interesting than high school.

Emboldened by my “bible,” I booked a meeting with the dean and presented my case for why my self-education was just as valuable, if not more, than a high school diploma. He listened to my arguments and asked, “What if we said that if you go back to high school and get your senior year English credit, we will then consider your application?”

I shook my head. “I’m not going back,” I said. “It would be compromising my beliefs.”

I was cocky, stubborn, and defiant. I told him that if he wanted to know whether I could read and write I’d be happy to provide some samples of my work. He agreed, and a couple of months later, in the spring after my nineteenth birthday, I received a letter of acceptance. Mom was impressed with how I’d subverted the system, but she was even more in awe of my steadfast—if not insufferable—confidence in myself. “You have a strong centre,” she told me.

***

In stereotypical Sapphic fashion, I met my first girlfriend in my freshman women’s studies class. Anya had short red hair and a wallet chain, and she rode a skateboard. I liked that she was five years older and didn’t seem to give a shit what anyone thought of her. We flirted for several weeks before we finally kissed.

I was building up the nerve to tell Mom about Anya when I was home one weekend in December. I knew she’d be accepting, but I was still terrified to come out to her. I was only just starting to come to terms with my sexuality. Besides Ellen and k.d. lang, there weren’t many celesbian role models back then. This was pre–L Word; it wasn’t yet cool to be gay. Same-sex marriage hadn’t been legalized. Matthew Shepard had just been beaten to death. As good as I had it, I was still scared. Mom and I talked about a lot of things, but we’d never spoken about my dating life, or lack thereof. Afraid of prying, she never asked me overtly personal questions, and I never offered up what was actually going on inside my head.

At one point that weekend, we were sitting in her sunroom when I finally blurted out, “I’m dating someone.” Before I could even mention Anya’s name, or her pronoun, Mom replied, “Wonderful! Invite her to Solstice!” She didn’t even flinch. Sometimes Mom was too cool.

***

Mom had been planning an intergenerational women’s winter solstice party, which that year happened to fall on a full moon. It would be the first time I’d be introducing my new girlfriend—essentially announcing “Yep, I’m gay!”—to twenty of our closest friends. I didn’t think it would come as a big surprise to anyone, but I still felt nervous and self-conscious. In any case, it soon became clear that I needn’t have worried about being the odd one.

When our guests arrived, Mom led everyone through a series of activities. First she got us each to light a candle and share our intentions for the next year. Then she got us all to hold hands, walk around in a circle, and chant, over and over, “Freedom comes from not hanging on, you gotta let go, let go-oh-oh!” (She explained that a witch named Sophia had taught her the chant.) Next she got us all to stand in a circle and make a human web by tossing balls of yarn to one another. We ended up tangled in a big stringy mess. Anya couldn’t stop giggling. Mom thought she was high. I imagine Anya thought the same about Mom.

For the pièce de résistance, Mom ushered us all outside into the back parking lot. “It’s time to howl at the full moon,” she announced. We huddled around in our parkas and stared up at the night sky. “Aaah- woooooh, aah-woooooh!” Mom led the group in a series of loud howls.

A neighbour soon yelled down: “Shut the fuck up!”

“It’s just me! Elaine!” Mom reassured him cheerfully.

Anya and I stood on the sidelines howling with laughter. I could see, from Anya’s point of view, how this party, and my mom, might seem a little bizarre. I’d always written Mom off as quirky or eccentric—until I came to realize that she was just as queer as me, if not more. Considering the word’s traditional meaning—“strange, peculiar, off-centre”—I’d say Mom managed to outqueer me at what was ostensibly my own coming-out party.

When I look back on everything now, as someone who’s more comfortable in their genderqueer skin, I remember feeling confident and self-assured about so many things and yet totally strange and unknown to myself. I didn’t quite fit in with either gender or in a world where people just followed the script handed down to them. But Mom’s out-there-ness made it okay for me to be myself and to live life on my own terms, just as she did. I’m immensely grateful to her for that. But in the end, the pendulum may have swung too far—in her approach to me, and more consequentially, to herself.

Excerpted from Dead Mom Walking by Rachel Matlow, available now from Viking.