On Friday, October 2nd, Clinic 554, the only clinic to provide clinical abortion access in the province of New Brunswick, closed after successive provincial governments refused to fund clinic-based abortions. Now, abortion access is restricted to three hospitals concentrated in two regions of the province.

It may feel like this headline is plucked from 1988, when those seeking an abortion were not protected by Section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms—the right to life, liberty, and security of person. Then, 32 years ago, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in R. v. Morgentaler that Section 251 of the Criminal Code (prohibiting abortion except where life or health of the woman was endangered as confirmed by at least two doctors) violated Section 7. The law of the land may have changed, but the law in New Brunswick remained.

Indeed, the premier of the day, Frank McKenna, refused to let Dr. Morgentaler operate an abortion clinic there (Morgentaler did it anyways). The province fought Morgentaler in court as New Brunswick continued to subscribe to the so called two-doctor rule, in violation of the Supreme Court of Canada ruling. Successive Liberal and Progressive Conservative premiers maintained the position of McKenna. Dr. Morgentaler died in 2013, yet the province of New Brunswick continued to litigate the issue until the Morgentaler clinic closed in 2014. In 2015, Premier Brian Gallant removed the two-doctor rule, meaning that those seeking an abortion could now receive one free of charge in three publicly funded hospitals.

Clinic 554 took the place of the Morgentaler clinic and continued to offer abortion services, in addition to being a family practice and an LGBTQIA2S+ centre of excellence. Although the Government of New Brunswick began offering abortion services in those three hospitals, it has yet to fund abortions in a clinic setting, which means those seeking an abortion at Clinic 554 have to pay out of pocket. Clinic 554 often provided abortions even when patients could not afford the cost of the service, which ultimately proved financially unsustainable for the clinic.

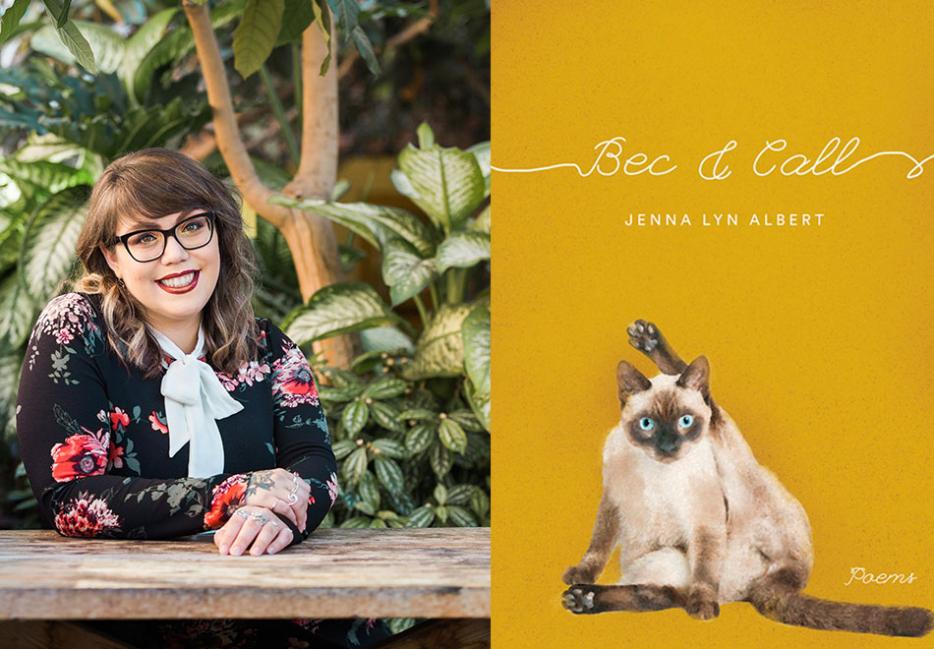

Activists, advocates, patients of Clinic 554, and concerned New Brunswickers alike mourned the closing of the clinic and engaged in various forms of advocacy to try to keep it open. Among them was Fredericton’s poet laureate, Jenna Lyn Albert, who used her platform to share a perspective that the 92-percent male Fredericton City Council wouldn’t necessarily have. For her regular reading to city council, she chose the poem “Those who need to hear this won’t listen” by Conyer Clayton, which details the experience of having an abortion. Two councillors were quick to decry the poem as “too political” and inappropriate for the Council setting—other councillors disagreed, and a community conversation ensued.

I spoke to Albert, most recently the author of the collection Bec & Call (Nightwood Editions), about the political power of poetry and the role it can play in Atlantic Canada.

Katie Davey: As poet laureate, you read poems at the Fredericton City Council meetings regularly. On September 28th, you selected a poem that was questioned by a few councillors. What happened?

Jenna Lyn Albert: Every two weeks, there is a regular City Council meeting. It's custom for me to share a poem during their moment of reflection. There was nothing particularly different about this council meeting. I prepared a poem. It was a poem by another poet, which is, again, typical. I don't read one of my own poems every single council meeting, partly to use my platform to share diverse voices. Rather than constantly hearing poems from just one person, it is a great way to lift up poets in the community and poets who are discussing pertinent topics.

So, I had chosen a poem that was about a poet's experience having an abortion. And I very intentionally chose that poem. That week, Clinic 554 was shutting down. It was timely, and [the closure was] cause for a big discussion in our community. A lot of people here in Fredericton are mourning the loss of the clinic, for multiple reasons, including for the lack of abortion access. Clinic 554 is also a centre of excellence for LGBTQIA2S+ healthcare. And [the clinic’s] Dr. Edgar is a family physician, so there are going to be 3,000 patients added to the waitlist for family doctors in the province.

I had introduced the poem by stating that the clinic was shutting down this week, and I was dedicating this poem to the clinic itself. I shared a few details about the poet and shared a little note that the poet had included with the poem.

One of the councillors, Dan Keenan, spoke up in opposition to the poem, feeling that it was too political, and that is not what the poet laureate role, or the intention of the moment of reflection, should have been. Another councillor also spoke up, Councillor Chase. One thing that was discussed was how, prior to there being a moment of reflection, that time was used for a prayer. [Chase said] they had gotten rid of the prayer because it was “too political,” which is not the case. They got rid of the prayer because the Supreme Court said that city council meetings should not have that religious aspect at the start of their meetings.

I got a little more information afterward. The former poet laureate, Ian Latourneau, was actually one of the inciting forces to having poetry read during that moment of reflection. It was just a moment of silence. And Ian asked if he could share poetry, and it became a tradition from his laureateship to mine.

So, if it isn't the role of the poet laureate to be political or to cause real reflection, what is the perceived role of the poet laureate?

I would say that it is, and I'm certainly not working outside of what poet laureates across Canada have done historically, and are still doing right now. I really took inspiration from other poet laureates. For example, El Jones and Rebecca Thomas are both former Halifax poet laureates. They certainly used their platforms to discuss really uncomfortable but important political issues. Rebecca Thomas wrote a poem about removing a statue of a colonizer and Halifax City Council considered it and the statue was removed.

I think what is surprising to so many people is the power that poetry can have. So often these [poet laureate] positions are perceived to be about painting cities or countries in a positive light and writing things that government officials would love you to write that are praising the beauty of a city, or an organization's important work. But when it comes to actual politics, which, it’s a municipal government body, so they're discussing politics in that forum. Some cities are really welcoming to that with their poet laureates and others are not. So, I think it's becoming a wider discussion, because I'm certainly not doing anything that hasn't been done before.

This isn't the first time you've experienced this type of pushback from the municipal government over the poem you selected, is it?

No. Back in June, I had made the request to share a video that a poet here in Fredericton had made. His name is Thandiwe McCarthy. It was in response to the Black Lives Matter movement and police violence, and systemic racism as a whole. The poem is called “enough,” and the only reason I reached out to the city council beforehand was because I wanted to share the actual poet’s video, rather than just reading it. I wanted that poem to come from the poet's mouth and not my own. When I wrote the city clerk, she passed it on to the mayor, and he said the poem was fine as long as it didn't deal with anti-police sentiment or use strong language.

On those grounds, I was not able to share the poem and instead read a poem, also about systemic racism, by Danez Smith that had no cursing and didn't explicitly call out law enforcement. When I informed Thandiwe McCarthy about what had happened, I let him know that if he did want to address this, whether it was with media or city council directly, that I would fully support him, whatever his choice may be, and once it made the news, city council very promptly changed their mind about allowing that poem in.

Growing up, my dad would always share music of the ‘60s and ‘70s with me and just say: “Listen to the words, Katie.” These words were often very political. He was sharing the sentiment and the politics, quite frankly. Isn't poetry the same? Isn’t it often political by nature?

It really is. There are certainly poems that are more of the fluffy, pretty kind of pastoral poetry that you might expect to read from the Romantic poets, but there are poets who, their entire careers, their entire collection of poems, are political. They explore issues that are really important. It's more than just pretty words. Even some of the poems that might seem like that just on the surface have more going on behind those vocal flourishes, which, it's again an opportunity to give voice to poetry. Rather than just having it read on the page, city councillors are able to hear a poet read these poems to them. It's another way of taking in the art form, where you're actually forced to listen. Or to be really kind of soaked in it in a way that—not always being on the page has that same effect. And that plays into the tradition of spoken word poetry. Often, it's kind of looked down upon as a lesser form of poetry, because it originated with disenfranchised groups, people who are LGBTQIA2S+ or BIPOC, or disabled, or in these other situations that make it so they might not have access to formal education in the poetic form. So, it's also hearkening back to some really old traditions of storytelling. That’s where poetry has that freedom. There's really a lot of importance behind those words. And hearing them proves a different experience.

In a place like Fredericton, or even more broadly, in New Brunswick, what role do you see the arts playing in actually shifting the narrative and contributing to change?

I'm really hopeful. With the current generation of poets and the future generations of poets, there has been a lot of change. Historically, in Fredericton, a lot of the poetic traditions here have been predominantly white, predominantly straight, predominantly male. And we're seeing now the power that female poets, Queer poets, Black and Indigenous poets have when they're able to be heard and have their poems given a platform, whether that's a spot in a literary journal, or a slot in a live event where they can share their poetry. It really has the chance to incite change.

I think a lot of people look at poetry, and they don't take it seriously, or they think it's boring. I always say that there's a poem that someone out there will love, even if they don't like poetry. It's not all sonnets. It's not all the things you learned in high school, there is poetry that's so diverse and has such different perspectives, and can educate and inform, and really change perspectives.

I think that's such a great transition into talking about your first collection of poems, Bec & Call. I ran out to Westminster Books and bought it as soon as it came out. I remember when I first started flipping through, I couldn't stop smiling. In so many ways, it really is beautifully New Brunswick, both the good and the bad. I found myself nodding my head in agreement. Tell me about the collection and about that writing process.

When I was writing the collection, I was reading so many different books by so many poets, and some of them were part of the New Brunswick canon, like Alden Nowlan, and others were new emerging poets from all across the country that had really new ways of writing poems, ways I hadn't even realized were possible when I was writing my own poetry, just taking in the works of other people and seeing, I didn't even know I could write about stuff like that. That's really when I stopped censoring the writing I was doing and started writing things that felt right to me, and things that felt like they needed to be put out on the page. That involved poems that were about sexuality and being a young woman in this province; that involved poems that dealt with poverty and being bilingual and feeling like I was losing that aspect of my language and culture. I grew up in Saint John, which is a primarily Anglophone city, so I always had that distance anyway from my Acadian culture, because my only access to it was through French immersion. I wrote about family—my family always jokes that all the dirty laundry was aired out in that poetry book, what else could she write about now?

It was really a personal collection of poetry that didn't just aim to write pretty words. It was intended to explore issues that were of concern. I remember moving to Fredericton and my first year here, I lived alone, and my mom had me download this tracking app so if anything ever happened to me, she would be able to find me if my phone was still on me. Because being a woman living alone in the capital city, that also, for a few years, was one of the cities that had the highest sexual assault rates, was terrifying to her. There were also some scandals in the CanLit community, with some professors and poets who had been accused of sexually assaulting students and young women that are in the poetry community especially. That really opened my eyes to the fact that sometimes, community can also be toxic and dangerous. It taught me a lot as a young woman in this industry about really knowing the people I was associating with. It really scared me to think that I could potentially be in these circles and not realize that the predators are right there. It scared me thinking that I could potentially be enabling that by either supporting them as an artist or facilitating events. It made me really cautious as a writer and as a community member.

In terms of what my impact was, what I was doing, and the potential dangers, it also made me more caring. When I was first starting to work on my manuscript, for example, I wrote a poem about missing and murdered Indigenous women. I realized after workshopping the poem and discussing it with some friends that I really trusted to critique my work that it really wasn't a poem that needed to come from me—it was one that was about an experience I couldn't identify with. The opportunity for that subject matter to be voiced should have gone to an Indigenous person. So, it was also just learning when not to write or speak, which I think for any poet is valuable. So that was a big part of the book, too— looking into the ethics of being a poet and a member of this broad community, not just here in Fredericton, but across Canada, and how to respond and be a part of that literary canon without causing harm.

Tell me a bit more about what it takes to be both a writer and a poet in Atlantic Canada.

It was intimidating at first because our communities are smaller, you don't have the same reach that poets in Toronto would have, for example, but the community is really strong and supportive. And if you want to write poetry, and get into literary magazines, being here in New Brunswick doesn't prevent that; you can still get your work out anywhere, which I like to remind some of the young poets that are just starting. You don't have to go to Toronto to study poetry or get published, you can do that anywhere. I chose New Brunswick and chose to stay here. I had the option to go to a few other universities for my MA, but I chose to stay here because I wanted to write about here and my experiences being Acadian. I felt like the opportunities I would have in New Brunswick would really benefit me. And to write about here, I felt I needed to be here.

How have your experiences with the municipal government in Fredericton shaped you as a writer and shaped your views on the role of poet laureate?

It’s really given me perspective. It's a very different audience from what I would typically present to; my poetry tends to be very feminist and bold. When I was reading for Council, I found I was trying to make selections that still kept the spirit of what my poetry is. I really tried to pick poems that dealt with subject matter that was important to people in Fredericton. When I chose my own poems, I did kind of pick and choose what would be received well, not necessarily censoring myself, though some poems I've read at Council would have had a curse word in it, for example, and I would have substituted it for something else because cursing is not particularly acceptable in those environments, which is a whole other discussion. I have some strong opinions on how people who have been historically disenfranchised shouldn't be criticized for using strong language to express their emotions and experiences.

It certainly also shaped my views on the power poetry can have. I always knew the potential harm and I always really thought about the potential harm that the words I was writing could cause. I didn't always think about the benefits that poetry can have. It wasn't that I wasn't cognizant that poetry can incite change. It's just I hadn't seen it in action in this way. I really first saw that with Ian, when he was doing his laureateship, and some of the other poet laureates across Canada. It's really an eye-opener to be in that position and to be given that platform to really share poems and art in ways that I hadn't been able to previously.

It was also really eye-opening to have the experience of trying to write commissioned poems. I've done some that were really difficult to write even if it was about things I was passionate about, like the 50th anniversary of bilingualism in New Brunswick. I wrote one for a local literary festival, Word Feast, and I really struggled with making sure I wrote a poem that was representative of what the festival was about. So, it was also a learning moment for me on how to write poems for, again, a different audience than what I'm used to. A lot of my audience has been young women, people that are queer, in academics, and other poets. When you're writing poetry for a crowd that might not love poetry or might not be familiar with it, you kind of write a little differently. And that's not necessarily bad, but it's writing in a different way. So, it's really been a teaching experience for me on how to write for a crowd that might not be the same crowd you'd have at a coffee house, or a rowdy literary event at the Capitol. It’s been really great to have that opportunity.