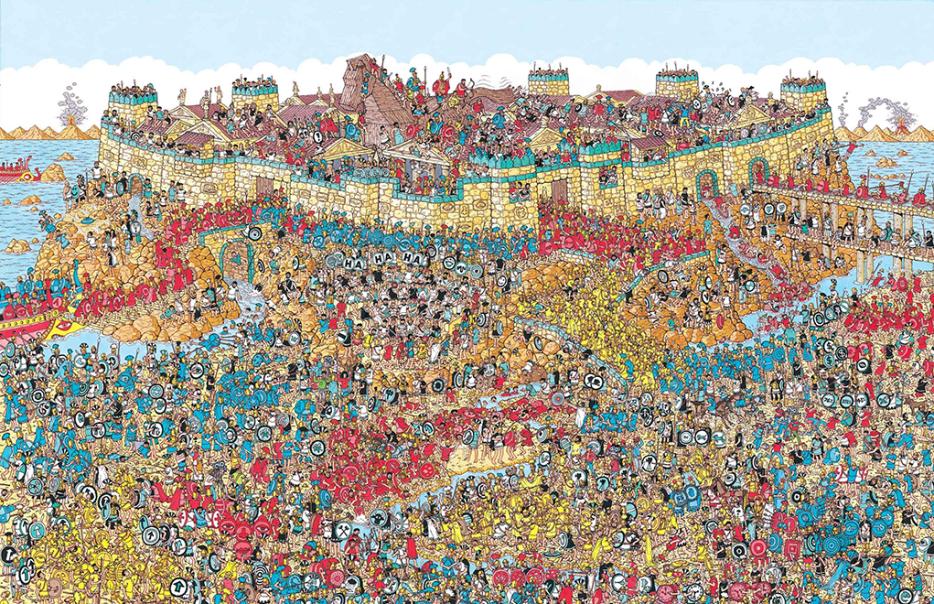

A hippie serenades his hairy friends, irritating two campers in the process, while a butler serves wine to a wealthy-looking couple nearby. An adjacent tent collapses flat on the person sleeping inside, as a watching crowd of kids laugh and parents scowl. A few feet away, children pull back a door to reveal a man in his boxers, women flock to a boat full of shirtless studs, and one man’s careless hammering sets off a chain of collisions and falls. Hikers pant with exhaustion, small animals pose for pictures, and mermaids pop out of the river. Overwhelmed? I hope not. There’s more than half of the scene to still explore, and Waldo hasn’t shown up yet.

Though the goofy cartoon characters and slapstick-y pratfalls populating Waldo’s travels aren’t immediately reminiscent of Renaissance art, the children’s classic Where’s Waldo? comes out of a tradition pioneered by Netherlandish artists Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel: men who created panoramas packed with figures both acting and being acted upon in imposingly dense scenes of life. Martin Handford, Waldo’s creator, has said each two page layout of a single scene takes him up to two months to finish, and that each complete collection contains hundreds of characters. This surplus of subjects is the hallmark of a wimmelbilderbuch, translated from the German as “teeming picture(s) book,” a book dedicated to and predicated on a “certain degree of disorder and chaos” as Cornelia Rémi puts it in her academic survey of the same. Since German illustrator Ali Mitgutsch created his first in the 1960s, they’ve evolved into something of a staple of children’s literature.

The books cultivate the curiosity they employ through their tacit faith that curiosity is not something that must be won or wrested from a lethargic and unclever mind but a pre-existing characteristic. They normalize intensive curiosity by embedding dozens of discrete scenes in one cohesive, large one. This cacophony of spectacle implies secrets among distractions; in a mass of people, at least one of those folks is bound to be doing something interesting. Because wimmel pictures are so obviously packed with information, viewers are inspired to be thorough in their gaze, to attend to each corner and shadow; any pocket of the scene may contain a satisfying surprise. Here, a ladder is knocked over and the painter is about to fall. There, the yelling of one angry driver distracts him from his imminent collision with another. There is no point in looking if you’re not going to look closely.

*

Though wimmelbooks are prime objects for philosophical reflection, little has been written about them (in English, anyway) beyond Rémi’s 2011 interrogation of their operation and effects. Consequently, her thoughtful essay is regarded as both seminal and definitive, though it neglects several important points. In her attempt to honor the mysterious, compelling quality of wimmel pictures, Rémi inadvertently undersells them. Wimmelbooks, she writes, must lack “clear rules or instructions,” otherwise the images lose the “remarkably open” quality that ensures “numerous elements might act together” in any variety of ways. This definition excludes all of the Where’s Waldo? series, Graeme Base books like The Eleventh Hour—an animal-animated rhyming mystery embedded with clues and codes—and even the otherwise text-free, US version of In The Town All Year Round (scenes of the same areas of a small town as it goes through the seasons) which provides suggestions of what readers should look out for where foreign versions did not. Worse, it obscures the intrinsic, seductive nature of a teeming picture in and of itself, which incites investigation and study by nature of its composition regardless of the book’s verbal container.

This luxury of complete discovery never arises outside of art.

A wimmelbook may imply or indicate outright that some elements are more valuable than others, even if that implication takes a form as simple as the title, which is the case with The Birthday Cake Mystery by The Tjong-Khing, a wordless depiction of various animal families over the course of one afternoon. (The title prioritizes the cake’s journey above other antics that take place throughout the tale, albeit with a light touch.) But readers—or more accurately, lookers—must ultimately discern important items from unimportant items on their own terms. Even if the early pages suggest where one’s attention should be focused, lookers’ own tastes and responses inevitably take the lead. Avid Waldo fans may be more excited when they find the tail of Woof, Waldo’s pet, than they are when they find Waldo himself. Others, like me, can recall tableaus from certain landscapes that don’t feature the recurring Waldo characters at all but are well-studied favorites nonetheless: a man’s flying carpet ripping on the top of a minaret, or the pet cats of two rival witches falling in love. Martin Handford professes a lifelong interest in crowds and chaos that seems to have seized his imagination with greater urgency than did Waldo himself. The character is simply the excuse to depict those raucous gatherings.

Why does this matter? Because wimmel images, including those centuries old paintings by Bosch and Breugel, allow each looker, young and grown alike, to create their own hierarchy of what matters the most. In this way, they replicate the opportunities for attention that arise in our everyday lives. Each living being around us is in a constant state of flux and sometimes in a state of emergency—about to fall from a ladder, or drive into another’s car. The mutable character of the world, which includes and influences the variability of our fellow living beings, is forever shifting our circumstances. In a reality teeming with other subjectivities operating in an infinitely dynamic environment, when and where and why we do we deploy our attention and investment? Wimmelbooks don’t provide any answers outright, but they offer exposure to this question again and again. They—limitedly—immerse us in the multitudinousness of life, which is so overwhelming in real time that we can rarely take it in.

Life is relentless.Wimmel pictures highlight this effulgence as they simultaneously tame it.

This luxury of complete discovery never arises outside of art. If you stare out your window at a truck about to back into a parked car, you’ll miss the funny face a girl on the sidewalk makes at her sibling in the same moment. If you watch two barflies showily make out, you miss the other two nearby who are in tears. Real life, or live life, also makes it difficult to share what you notice with others. Think of any moment when you tried to point out to a companion a celebrity who passed out of view too quickly for them to catch, or a fiercely arguing couple, or a car with a strange paint job. We regularly see things that we cannot share. Observation can make for a lonely pastime when the scene in question is not frozen and arranged to be exposed.

*

“What’s happening?” our brains wonder when we encounter living figures in art. Actions cause reactions; actions produce consequences. This elementary truth, courtesy of time and human nature, is the source of storytelling, and it’s responsible for the way we usually understand the world. Even wimmelbooks’ distant grandfather, the fantastical painter Bosch, whose work later influenced the Surrealists, composed his scenes to include chronological and narrative designs. The plain image of someone carrying a cake already speaks to a history and a future, to specific circumstances that led up to and will follow that exact moment. It is how existence works. We ask “what’s happening?” because we know there’s a story.

And in life, there is always a story because there’s always something happening. Or rather, there are billions of somethings happening in every second, every split second, every quarter second. The slightly malevolent undertones of “teeming” hint at this, as do the other vaguely menacing translations of wimmel: swarming, crawling, bristling, overrun by. Life is relentless. It does not stop, and there is so much of it. Wimmel pictures highlight this effulgence as they simultaneously tame it. Through the elimination of actual motion, time stops, and viewers can take as long as they like to study the visual information with which they’re presented. Wimmelbooks create a world where everyone is deserving of acknowledgment, and we are given the time to bestow it. We can locate Waldo, Woof, the missing parrot, Hannah, and the birthday cake, but only nestled within a spread of life that clamors for equal consideration, and leaves us with more questions than answers.

When Slate’s Ben Blatt tried to ascertain a pattern as to where Waldo usually materializes in his books’ pages, he determined two precisely placed horizontal bands within which viewers would have the most luck spotting the missing man. But solving the books’ titular mystery provides him with little satisfaction. “That leaves a more intriguing question left unanswered,” Blatt writes. “Why is Waldo there? Why, Waldo?” Images can reveal only so much. The rest is lost to us, swept away in the swarm of ordinary life.