What grown man can say that he married his own mother, and that although heartbreak was involved, no-one disapproved? At least not for the obvious reasons.

Science, as well as anecdotal evidence, tells us we can’t recall our time in the womb let alone form memories before the age of two or three. But Ebbing could. Ebbing experienced things; some of which would have been better left mired in the swamps of infantile amnesia, swallowed whole by the alligators that patrol those brackish shallows.

Ebbing had perfect fetal recall.

In the beginning and at the end it’s all about the heartbeat. In between there is this temporal thing we cling to we call life.

At three weeks Ebbing, as large as a poppy seed, experienced his own heartbeat. A vivid tapping against his microbe-sized chest wall—exhilarating, but also frightening. Was this him? Or something trying to escape? And close by, too close, another. A faint pinprick that was his first encounter with pain, followed immediately by yet another sensation, one that smoothed over the hurt. He felt it as a cat’s tongue, as warm wax.

At eighteen weeks, two days, seven minutes and thirty-three seconds, Ebbing could hear. There wasn’t anything gradual about it. One moment nothing but physical sensations—the tapping, pricking, licking, floating—the next moment the sharp clack of castanets. Ebbing had an instant recollection of nights redolent with paprika fried potatoes and grilled sardines, an earthy-smelling woman leaning close, someone dancing, always someone dancing and singing off-key in the dark.

A heartbeat besides his own joined in, a weak but distinct chiming, and over it all, an immodest banging, like the kettle drum in an orchestra. A celebratory boom boom boom boom that could be heard as well as felt throughout his blood stream. Maternal love as a victory march.

And after that, the invasion of the world: One hundred and one trombones and a clarinet, a thousand scorching guitar licks of “Smoke on the Water” in numbing 4/4 time, the horrors of the pipe organ in the haunted mansions of God, frenzied banjos, dueling ouds and gamelans, the tinny pa rum pa pump um of toy snares, the itchy buzz of tissue on comb, the whistle of air through a blade of grass, the sonic-boom crack of a bullwhip splitting the air.

With the collaborative effort of dawning hair follicles in his embryonic cochlea Ebbing learned to filter out the cacophony. His mother’s heartbeat, sometimes a harpsichord, which plucked pleasantly at his own, sometimes a dobro, causing him to tap his incipient toes, could now be heard above the din. But Ebbing could not mute that close-by insistent drone of the omnipresent bladder pipe.

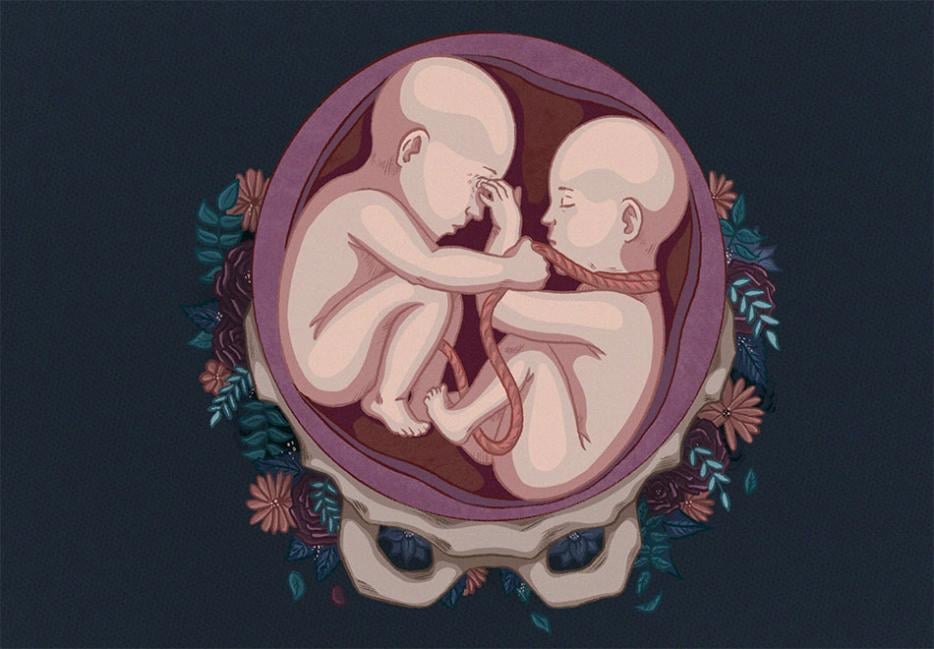

At twenty weeks in the womb they were both still blind, Ebbing and the girl who would have been called Bente. Together but apart, each in an amniotic sac like a goldfish in a plastic bag—a precarious position for both fetus and pet fish, depending on who’s doing the carrying. Each in its own placenta, a cosmonaut and an astronaut hurtling towards a Cold-War earth, their prematurely ejected landing pods on a collision course with each other. Houston, uh, Houston?

Bente was the very definition of a bad roommate. Petulant and noisy, eating food clearly marked “Ebbing,” never cleaning up after herself, sprawling madly out in all directions, taking up more that her designated share of a finite space. Her heartbeat competed with Ebbing's. Rather than the mellow groove he now preferred, she insisted on a wild syncopation, causing their mother to rush to the doctor's office on more than one occasion.

At twenty-two weeks, the one who would have been called Bente sounded like teeth on glass, the sharp grinding of a garbage truck down a war-ravaged roadway, that zany aunt—the life of the party—who loves to sing but is utterly tone deaf.

Amidst this racket Ebbing could barely feel his own heartbeat, let alone hear it. The beloved mother was muffled by the atonal regurgitations of his twin who endlessly flailed and pressed too close. Ebbing, bereft, enraged, could see for the first and last time in his life. He actually saw red, or rather, witnessed it as a wild, hot flaring of crimson and carmine in front of which twisted and writhed ancient Pyrrhic dancers primed for battle, swords in hand. Their lust for victory infectious.

He tugged at his own fleshy lifeline with spindly fingers, testing the resilience of the blood-ripe cord. Wrapping it taut around the one who would never be Bente, he played her like a old-time fiddle. She was his first instrument. The sounds of his sister’s weakening heartbeat were almost pleasant, a flutter-tongued flute. Their one and only duet.

Ebbing would never include a flute in any of his compositions.

She did not go without a fight. Her own alien fingers with their tiny, serrated nails scrabbled at Ebbing, clawing and shredding wherever she managed to make purchase.

The only music in the hours that followed besides his own was his mother’s heart, a juddering klaxon.

When he was a small boy, Ebbing loved sitting in his mother’s lap as she told the story of when she first heard his heartbeat. Better than even The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin or Horton Hears a Who. “You sounded like a panting dog, panting so fast and hard it scared me to death. ‘What’s wrong?!’ I asked Dr. Heppner. ‘What is wrong with my dear boy?!’ She told me nothing, nothing at all was wrong. That it was perfectly normal, and as the baby gets bigger the heartbeat would slow...”

“Show me, show me!” Ebbing would chitter.

And his mother panted and panted like a dog until they both melted into laughter.

She never mentioned the one who would have been called Bente. Both his mother and father thought it better if Ebbing didn’t know. But sometimes in her heartbeat he could detect the profound melancholy of someone singing fado, the saddest music in the world.

The specialists had never seen a pre-natal injury like it—both corneas so scarred that under a magnifying glass they looked like the surface of an ice rink after a play-off game. And no Zamboni in the world could repair this damage. Other than the blindness, the boy was perfectly healthy, perfectly normal.

A few days after his fifth birthday Ebbing, a boy the other Kindergarteners called Froggy, was plopped on the bench in front of an upright grand in the downstairs den of the middle-aged widow across the street from his family home. The piano teacher played “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” with alarming conviction and then said, “Wouldn’t it be fun to learn how to do that?”

Eyelids closed against his protruding orbs, Ebbing tapped at the keyboard with one finger, then spread his hands wide and played the notes he had begun composing before he’d even been born. In the corner of the room, on the shabby loveseat that had been banished to the basement years ago, sat his mother, heart swelling as the music burst through the confines of the room.

At twelve, as a thin, red-headed kid in black tie and tails, Ebbing made his professional debut. Playing at first as an innocent floating inside the womb, lulling the audience into submission, creating a sense of false security with a pleasing Satie-like minimalism before releasing the hounds. A few of the older patrons stumbled towards the exits, mad dogs baying at their heels. In the front row of the Orpheum sat his proud but bewildered parents, his mother’s hands clutched her chest, no idea she was his living metronome. The word genius was bandied about.

Five years later The Ensemble Modern in Frankfurt performed his first full orchestral composition, placental declarations in the dark. The orchestra had collaborated with György Ligeti, Steve Reich, Frank Zappa, and now the seventeen-year-old New Music wunderkind from Vancouver, Canada. But Ebbing wasn’t in attendance. He haunted his mother’s bedside at St. Paul’s Hospital. Her heartbeat was as strong as ever but her white blood cells were fleeing like villagers escaping a Viking raid, their shrieks tearing holes in the air, their hair alight.

Ebbing tried to follow his mother’s heart, packed in ice inside a picnic cooler, as it was transported by helicopter from St. Paul’s to Surrey Memorial Hospital. Maybe it was the chop of the propellers, the screams of the gulls, the guttural coughing from the adjoining hospital room, his father’s gulping sobs, the sentimental Tin Pan Alley AABA refrain issuing from his own chest, but Ebbing couldn’t make out a single maternal note. The woman in the bed had disappeared as if she’d never been.

This is where the music dies, he thought.

At Mountain View Cemetery, Ebbing didn’t listen as an old family friend recited a bowdlerized version of Auden’s “Stop all the Clocks.” He was tuned to a distant frequency—he could hear it across the miles, a stately hum like a Theremin.

It had started seven hours, 36 minutes and 8 seconds after his mother was declared brain dead. During those leaden hours Ebbing had been transported back to the womb, before he could hear, before he could even feel. He was less than three weeks old again; he might as well have been a poppy seed caught in someone’s teeth.

Ebbing experienced the sound first as a vibration in his chest and he was born again.

Patience was never the strongest of Ebbing’s qualities. But he waited until the steady, quiet hum began to oscillate, transforming into a more complex beckoning. At its highest registers he heard Jessye Norman performing the twin Sieglinde in The Valkyrie. He waited two years, never once approaching a piano during that entire time.

Her name was Sanjeeta and she’d been born with a congenital anomaly that didn’t announce itself until she was twenty-two and soon to be married to a man from Haridwar whom she had never met. Her parents thought it a satisfactory match. His parents, learning about her defective heart, did not.

Three years later her heart was traded for another and she spent two years and a half a morning recovering from the shame she had brought onto her family. Defect was not a word they with which they liked to associate.

Sanjeeta was sitting in the garden when the back gate scraped open and a young man came in and bit by bit stole her borrowed heart. Her father called him The Blind Beggar. But it was he who was the beggar and could not afford to be a chooser. Sanjeeta’s mother found something too familiar about Ebbing’s music, as if she had heard it before but could not recall where. And that blind rhesus monkey by the river in Ayodhya when she was only twelve had looked at her the same way before baring its teeth. But her husband had decided.

Ebbing’s father said she was lovely, but – (Meaning too old).

His aunt said she was too old for him, and – (Meaning too brown).

But what is old, to someone who has only ever experienced age as sound? What is skin tone, to someone who has only experienced colour through music?

At age twenty, Ebbing lay in a hotel room with his new wife and ran his fingers along the thin, puckered seam between her breasts. She caught his hand and said, “My shame.” But all the virgin bridegroom could hear was a celebratory boom boom boom as he went tunneling into a place from which he would never emerge.

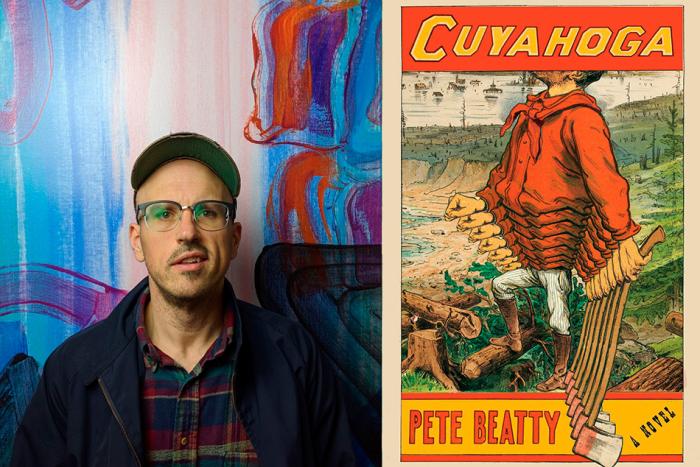

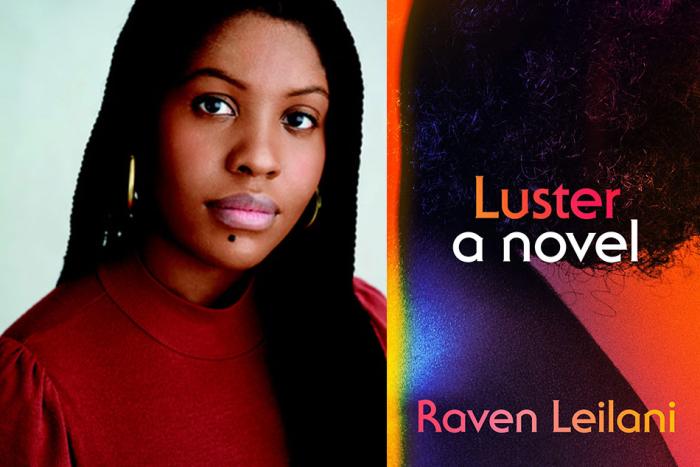

Excerpted from The Beguiling by Zsuzsi Gartner, Hamish Hamilton 2020