When Wanda bought the house, she didn’t imagine that anyone in the community would recognize that she and Lynn were queer.

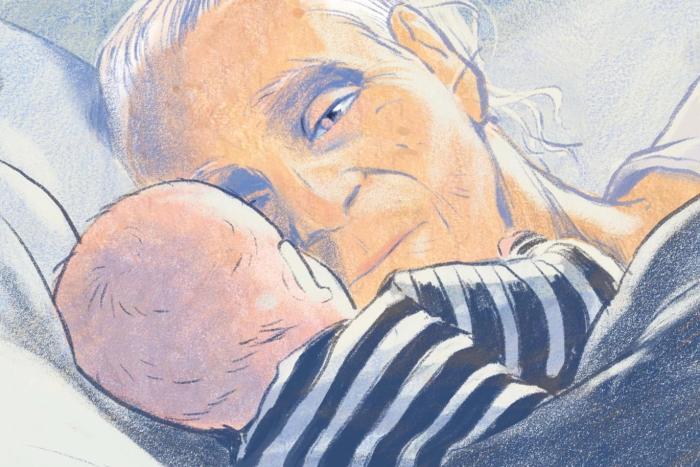

The baby had come from a place none of us could remember. Our grandmother was headed there.

Latest

When Wanda bought the house, she didn’t imagine that anyone in the community would recognize that she and Lynn were queer.

The baby had come from a place none of us could remember. Our grandmother was headed there.

The author of Mother of God discusses the limitations of realism, Frank Bidart, and the anguished duality of shame.

Standing in the wreckage of these spaces unlocks a sensation people often crave, but can’t name.

It’s an imagined past, a pastoral imaginary, an alternate timeline in the multiverse.

Threading a needle is a momentary sideline from a feeling that might otherwise darken me completely. That can be enough, and as a new decade approaches, I find peace in enough.

Taking care of living things is a science of intuition—I had no guarantee that my choices would be more helpful than harmful.

The popularity of the Storm Area 51 meme could easily be read as a cry for help—as though if we save the aliens from the government, they can, in turn, save us from ourselves.

The standard explanations for why things have happened this year have turned out to be as useless as the most far-out conspiracy theories.

I don’t have a title sitting in the car. There is anonymity in that moment, a complete lack of pressure. I’m just the driver, caught in a free, smooth space between eddies.

When I finally managed to get out of bed and return to my life, I was determined to be an expert on how to grieve. I was going to fuck grief up so hard.