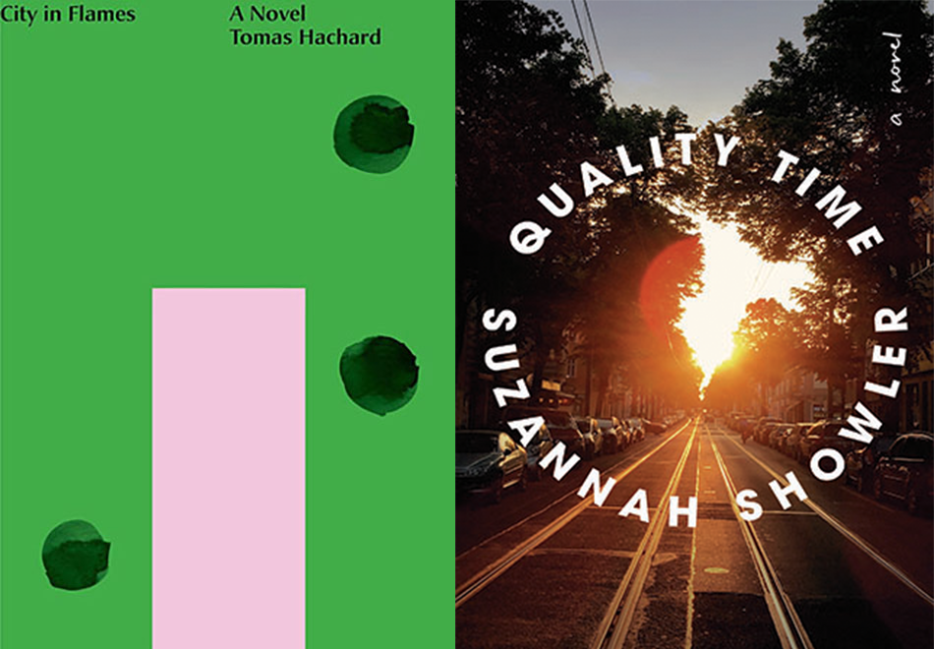

Tomas Hachard: One of the things I loved about your novel Quality Time (McClelland & Stewart) is how vividly it depicts Toronto in the early 2010s, this time when the city is shifting in front of the characters. You really feel how the main characters Lydie and Nico live in the city, move through the city. It’s true to a certain stage in life when you’re biking everywhere, going to multiple places in one night. It feels very alive.

But I also know—and hopefully I’m not breaking some authorial mystique here—that you’ve lived in many cities, big and small, in your adult life. So I guess I want to start by asking, why Toronto? And maybe more generally, what got you interested in making the city part of the story in the way that it is?

Suzannah Showler: Mystique busted! All my mystique—gone!

The simple answer to this is that the scaffolding of Quality Time was built from several scraps of unfinished or failed bits of other writing, all of which were generated either when I lived in Toronto or in the period shortly thereafter. So, the sense of Toronto and its place-ness was a lot closer to me when I produced those pieces of work, even if my own history in the city was further away by the time I was actually writing the novel.

I lived in Toronto for only five years, but somehow those are the years I think of when I think of “my twenties,” you know? My associations with that particular time of life are set against the backdrop of Toronto and that precise moment in the city’s history—the era of Occupy, and Rob Ford, and the G20 protests. That time felt very specific to me—maybe just because anything a person experiences at the height of youth feels specific.

Not to get too far into my own feelings about it or whatever, but I remember when I first moved away from Toronto, I used to say that it felt like stepping off a still-moving treadmill. Like suddenly you can see that the ground there is moving at this wild rate, and you realize how bonkers it was that you were sprinting that fast just to stay still. I still have a very strong home feeling in Toronto, though—a feeling of familiarity that hasn’t quite left me.

I wanted to ask you about Toronto, too. Because Toronto is very pointedly not the backdrop of your novel City in Flames (Flying Books), but I think for a lot of people who are familiar with the city, it will be tempting to read Hillside as a Toronto substitute. Sara is studying in London, which is a real place. So, I wanted to ask about the decision to set the other half of the story in a fictionalized place in an otherwise recognizable world. I guess that’s the fancy way of asking, and the unfancy way of asking is: Is Hillside secretly Toronto? Do you picture Toronto when you picture the backdrop for the story?

TH: The answer to that probably changed as I wrote the novel, to be honest, and as Hillside developed in my mind. But I think Hillside is very much Toronto-like. It certainly feeds a lot from my experiences of Toronto, and there are parts of Hillside that I picture as Toronto—City Hall for instance, which is where some important parts of the novel take place.

But my intent wasn’t to be covert. On the one hand, there’s a really simple reason that I kept it to Hillside, which is that I didn’t want to be stuck with Toronto as it actually is. I wanted to make pieces up. And maybe that points to the more substantive reason as well, which is that I wanted the politics of the novel to not be correlated with a particular place, because I wanted to get at the deeper resonance of the populism and authoritarianism that develops throughout the book. Much of City in Flames is about control—the loss of control, the search for control, and the assertion of control. I wanted Hillside to be a place where I could explore those feelings, which we’re seeing emerge all around the world, without being confined to a single iteration.

But getting back to my first reason, did you find it a struggle in any way, sticking to the “real” Toronto? Your book is so much about memory, and our memories of places can quickly differ from what was there.

SS: It was a struggle, in a way. I found myself doing research about a time and place that I’d personally lived through not all that long ago. I would turn to the rollback function on Google Maps to walk down a street, for example, or watch videos shot by tourists at Casa Loma. And I have this Excel spreadsheet that keeps tabs on Lydie and Nico’s anniversaries overlaid against all kinds of things that were taking place in Toronto at the time. I spent many hours cruising through the archives of Torontoist (RIP!), which was the first venue I ever wrote non-fiction for. (Shout-out to David Topping, who was editor-in-chief at the time.) That was a really excellent resource for trying to find the temperature of the city in the late aughts on both a micro and macro level.

I used to do work as a fact-checker for magazines (one of my favourite jobs ever, by the way), and I sometimes find myself, even when I’m writing fiction, picturing someone asking for a fact-checking package at the end of it. I’m not sure who I think is going to call me to account in this way.

TH: This was my fear exactly, probably because I also wrote a lot of non-fiction beforehand. And so, I’ll be honest, I never even really considered setting the novel in Toronto. It was always this other city, this Hillside, which I wanted to invent, maybe in part because I was also trying to generally explore how we invent communities for ourselves.

SS: I want to ask you about invented communities. And also about invented feelings, or bonds in general. The first part of this question is about the message boards that Sara falls into from afar, which function as kind of a Hillside political subreddit which Sara is drawn to at a time when she’s far away from the action. I’m wondering if you could just say a bit about what you see the role of that online community being in a novel that’s so interested in places.

And then about invented feelings, I also want to ask: Is City in Flames a love story, do you think? I want to say that it is, but I realize that there’s something absurd about that. Kevin and Sara’s bond is keeping them glued to their phones, and estranging them from the world. But all love is absurd, no? Discuss.

TH: I think it’s a love story, definitely. I mean at the very least I think it’s about this love that springs up between Kevin and Sara in, as you say, a somewhat absurd way.

I guess to get to the full question you had there, and going back to the cities theme a bit, to me the city, whether Hillside or London, is important to the novel because it’s where we really live politics. Where you and I collide and have to deal with the consequences of that collision. And that is something I’ve always been interested in: how people collide and all the joy and mess that comes with that.

But, at the same time, the internet has changed that to a great extent. Now we might collide with people as much, or much more, on the internet than we do in cities or towns, or in our communities. And the message board Sara gets embroiled in is a piece of that, but so is Sara and Kevin’s relationship, which is confined largely to an app, to the point that they refer to their relationship as their conversation. These are both spaces of invention in the same way that cities are spaces of invention, and there can be a really dangerous quality to that. If too many people are inventing themselves at once, without any check on it, there’s a loss of reality.

Kevin and Sara’s conversation is much more beneficial than the message board in that way. Their bond is real, even if they question it from time to time. But there’s a tension there as well because they know they are creating versions of themselves for each other—the versions they would most want to be. And maybe one question in the novel is whether, through that invention, they can turn into those people in “real life.” And whether that’s so different from when we fall in love in “real life.” Because that also is about finding a space where the person you wanted to be can finally exist.

SS: As someone who wrote a book about The Bachelor franchise and considers themselves a kind of unaffiliated Bachelor scholar, I am 100 percent on board with the idea that real romantic feelings can develop under unreal conditions. Also, I really like the idea of “finding a space where the person you wanted to be can finally exist” as one definition for romantic love. I think that’s something that gets neglected in romance discourse: love can be a place in which to idealize oneself, not just the object of your affection. And not necessarily in a bad way at all, like you’re saying.

TH: I saw something similar in Nico and Lydie. It’s interesting to me that they are products of a city, just in the sense that they collide at a bar one night and their story unfolds from there. Then they create their own world, with the anniversaries of their first year together that they celebrate on a daily basis year after year, which becomes hard to break out of. To be provocative, their love story might be experienced as a trap. Maybe one way of asking my question is: Were Nico and Lydie meant to be? Did they need each other to break into the next part of their lives?

SS: Yeah, I think something our novels have in common is this sense of an imperfect or unreal or hyperreal bond being nonetheless meaningful. Like you, I also wanted to explore the elements of invention that take place through social relations. And with Lydie and Nico’s anniversaries, I was hoping to literalize or hyperbolize something that I think is kind of normal, both in terms of how we experience romance and also how we experience time. Like, I think it’s common for falling in love to create a kind of hermetically sealed shared universe, and with it a private understanding of how time feels as it passes.

The way Lydie and Nico go about it with the anniversaries is a bit intense and, as you’ve said, it becomes a kind of trap, but I think the thing they’re trying to get at, the thing that they’re claiming, has a truth to it, you know? Like, Lydie and Nico are living in their own world, and one of the things I was working through was: Is that a bad thing? Is that allowed? Is it a joke? Are they making art? Or are they just doing something deeply, frustratingly indulgent? Or all of these things?

With the time stuff, I was borrowing a lot from the twentieth century philosopher Henri Bergson and his notion of duration—which is basically about the way time feels when we live it, as opposed to how it’s enumerated when we account for it. When Nico spins off from the anniversaries and starts to do his own thing with it, his ideas are direct bastardizations of Bergson’s thought. It was kind of an experiment to me, like, what would Bergson’s ideas look like if they were run through a weird twenty-first century lens—one tinged by both (left-ish) libertarianism and the cult of optimization? Like what might Bergson look like in an age of content creation?

Anyway, to get back to the relationship: I like your reading of the fated element to Lydie and Nico—that they are “meant to be,” but the thing they’re meant to be to one another doesn’t ultimately have to do with permanence, maybe? I think you could say the same thing about Kevin and Sara, right? This is a book about how they both grow up, or grow through one another. I’m tempted to ask you about the ending . . .

TH: That’s a fair temptation! I think what you said before—that being meant to be doesn’t have to be associated with permanence—is part of what Kevin and Sara struggle with throughout the book. Sara and Kevin meet online through a glitch in their dating app, and she at one point laughs at the idea that this means that they were meant to be.

To me, without spoiling too much, the question of how Sara and Kevin change through each other is as important as their fate at the end. And it’s tied to the question of what we choose and what gets chosen for us—or you might say what we choose and what is “meant to be”—which came to the fore more and more as I wrote the novel. I think the growth you talk about in Kevin and Sara is tied to regaining empowerment, an ability to act on the world, but doing so in a constructive rather than destructive way, because that same empowerment is also a seed for the oppression in the novel.

I was struck by something you said at your book launch, which is that this book was a way to reconcile yourself with growing up, becoming an adult. But Nico and Lydie grow up in very different ways in the book, and not necessarily in good ways, ultimately. So, do you feel this book taught you how to grow up? Or is there a piece of it that still wants to question that concept?

SS: I think I stand by that? I think it’s mostly true? Or maybe it would be more accurate to say that I was writing this book and at the same time when I was trying to find my way to some final piece of adulthood that seemed to be a point of resistance for me.

One thing, of course, is that the trappings of what we’re taught to think of as adulthood—a stable job, property ownership, wealth accrual, marriage, procreation—have been absorbed into neoliberalism, right? So, I think one thing I was struggling with is something like: how to reconceptualize adulthood? Maybe along lines of, like, self-knowledge, or artistic fulfilment, or the capacity to offer care? I’m just trying to work through some of the structuring narratives we’ve been handed down and figuring out which ones have real meaning to me and which don’t. Those are issues that Lydie and Nico grapple with, too, if not always head-on.

I wasn’t in town for your book launch: Did you get asked why you wrote City in Flames? Has anyone asked you that yet? Can I be the first one? Why did you write this?

TH: I’ve been asked that question a few times, mostly because no one expected me to write a novel. So usually it comes from shock—like, really? A novel? Where did that come from?

And I get it. I also am shocked, frankly, even if the book didn’t come out of nowhere. There is a thread that runs from it through to my past writing and, really, back to university. I’ve always been interested, like we talked about before, in the space between people, and how it’s this tumultuous and unpredictable place where the world—at least the social world—is born. And as a corollary to that I’ve always been interested in solitude and people who retreat from those spaces and the world. On the one hand, I suppose, there’s the desire for self-certainty and a firm identity. And on the other hand, the fact that our encounters with other people can completely disarm us.

I had explored that dualism in some way starting with my short-lived philosophy career and then in my reviews and essays (whenever I could force it into whatever I was actually supposed to be writing about). Then when I moved away from writing full-time to other things, I didn’t expect to do anything more with it. But eventually I started writing fiction in my spare time and gravitated toward those same issues. Now I have no hope that I’ve worked through them entirely, but I do feel closer to some peace about them.